Training Performance Horses

Lesson Eight

TWO TRACKS, SHOULDER-IN RENVERS

Suppleness, the fifth element of training, is an absolute requirement if horse and rider are ever to achieve unity in performance.

Suppleness is not looseness, and it is not flexibility. True suppleness indicates an advanced stage of training for the unrestricted horse, since it demonstrates the horse’s ability to adjust by yielding.

A horse is said to be unrestricted if he accepts his rider without tightening his back muscles and then he willingly begins a well-timed trot without having any rein contact. He must also continue to trot with relaxed body and back muscles, maintain a pleasant expression by having his ears half erect in attention to the path and rider, and carry his tail with a natural swinging rhythm.

Suppleness is initiated by the rider’s request for more forceful driving action of the hindquarters as the horse stretches forward to reach the bit. The mouth, poll and neck should yield. As the horse gains suppleness, he will be capable of subtle lateral work.

The supple horse has the ability to shift his balance point forward and back, as well as from side to side without stiffness or resistance. He is pliable. This is seen in his adjustments of carriage (longitudinal) and (lateral) bend. The supple horse is moldable and can be rounded and shaped.

Suppleness is most easily seen in transitions from gait to gait as the horse’s body yields to new demands. As the horse’s body shortens or lengthens in response to the changing engagement of the hindquarters, the supple horse responds smoothly and seemingly without effort.

Stiffness is the opposite of suppleness and is easily witnessed or felt when the horse is unable to drive his hindquarters under himself in downward transitions. When changing from a canter to a trot, for example, the horse should slow and balance himself on his hind feet, then lengthen his body to engage in the newly requested gait. The stiff horse will leave his hind legs rigidly behind and throw his balance into the rider’s hands as he looks for support.

Suppleness is dependent upon and stimulated by impulsion, the increased driving power elicited from the hindquarters. Suppleness is complete when the energy of the horse flows from the hindquarters through the cues given by the rider and into the requested movement. The truly supple horse will be filled with power, but will be completely relaxed, and will chew the bit correctly--soft and easy, with no sound, but with an increase of saliva in the mouth.

A horse, which grinds his teeth, or tries to hold the bit with his teeth, is showing signs of discomfort and resistance and is not supple.

The half-halt is the best exercise to test for suppleness. If the horse instantly responds to the half-halt cue, then the horse is supple and ready for a transition of gait. If the instant response is not forthcoming, the horse is not supple, and the transition should not be executed. Repeat half-halt cues until immediate response is elicited, then make the transition.

TWO-TRACKING and LEG YIELDING

Let’s start with two-tracking and leg yielding. These are relatively easy exercises for a horse, and both are good preparatory work for the more advanced and precise shoulder-in, haunches out and haunches in. Two-tracking will eventually become half-passing, and is also the beginning of the western side-pass.

When two-tracking, the horse’s body remains

straight, while moving on a 45 degree angle to the direction of travel.

TWO-TRACKING

To teach a horse to two-track, travel along a fence line and gently but consistently ask the horse to move his hindquarters away from the fence and toward the center of your circle.

When first teaching this exercise, begin at the walk. No fast action is required of the horse. It is permissible during early training to turn the horse’s forehand into the fence by using an indirect rein as well as some inside leg pressure at the girth. If you are moving to the left with the fence line on your right, for example, push the horse’s hindquarters out with your right leg. At the same time use the left rein, an indirect rein, to block the horse’s forehand movement. This slows the forehand and allows the hindquarters to move out more easily. You can also use some left leg pressure to slow the forehand, actually pushing it slightly into the fence line.

Try not to use direct rein (in this case, right rein) to pull the horse’s head toward the fence line. Such action usually causes the horse to counter bend and move with his head away from the direction of travel. The horse should always have his nose pointed in the direction of travel.

If you are moving to the right with the fence line on the horse’s left side, begin the exercise by asking the horse to move his hindquarters to the right. The request is made by applying left leg pressure well behind the girth. Simply try to gently push the hindquarters toward the right. Don’t kick in an attempt to force the hindquarters over.

If the horse does not yet fully understand what is being asked, assist him by turning his forehand to the fence. Forward movement must continue, but it is not necessary to do more than walk. To move the forehand into the fence, push an indirect rein into the horse’s neck and apply leg pressure at the girth on the same side. These cues should cause the forehand to move in the opposite direction of the hindquarters, which should bring the horse to a 45-degree angle to the fence line. At first the horse may stop his forward movement, or simply try to resist any or all of the cues. To give the horse additional help, the rider may shift his weight to the horse’s side opposite the direction of travel, which in combination with the other cues often helps a young horse move laterally, away from the weight shift. A rider’s weight away from the direction of travel can be used only with lateral actions which involve no sharp turns.

Two-tracking is not difficult for the horse to learn, so he should pick up the cue requests with just a little practice. Ask the horse to two-track down the long side of the arena, and then straighten the horse along the short side. When you approach the long side, again ask for a two-track performance.

When two-tracking to the right, for example, the horse will create a set of forehand tracks just off the rail. The horse’s left foreleg and left hind will cross over the horse’s right foreleg and right hind when moving to the right if performing correctly. The horse should create a separate second set of hindquarter tracks toward the inside of the circle--thus the exercise name--two-tracking.

Once the horse understands the exercise, the rider should remain balanced in the center of his horse, ask the horse to hold the forehead in position by applying a light indirect blocking rein and move the hindquarters to the inside of the circle by applying light outside leg pressure behind the girth.

If the movement is executed correctly, the horse does not turn his head away from the direction of travel, but continues to maintain some inside bend. Maintaining a slight degree of inside bend is the first step toward supplying the horse.

Half-Pass

An advanced supple and solidly paced two-track can become a half-pass, which is simply a forward and sideways movement at the same time. The advanced horse may half-pass at the walk, trot or canter.

If the horse is traveling down the left fence of an arena, the rider may half-pass the horse to the right by simply applying two-tracking cues to push the horse to the right, but instead of blocking the forehand, the rider lets it move with the hindquarters so the horse’s body remains parallel to the fence line.

In both two-tracking and half-passing, the horse holds his body straight. Two-tracking takes a 45-degree angle to the path of travel. Half-passing moves off the path of travel, but remains parallel to the path.

In half-passing to the right, for example, the rider applied left leg pressure behind the girth to move the hindquarters to the right, while also applying light indirect left rein pressure to move the forehand to the right. It is important the horse maintains his correct head position, slightly tipped to the right, and that the horse’s forehand actually leads the hindquarters. It is never correct for the hindquarters to get ahead of the forehand.

Once the horse learns to two-track, leg yielding comes relatively easy.

LEG YIELD

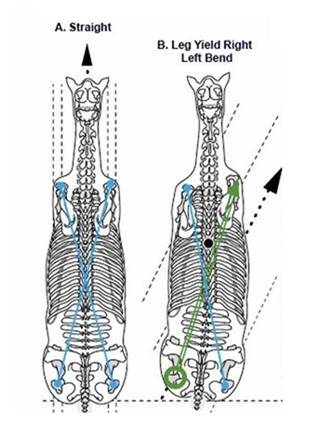

To leg yield, the horse simply moves away from the rider’s leg pressure while allowing his body to bend around the rider’s leg. If the horse is moving on a circle to the right, the rider may leg yield the horse to the left by applying right leg pressure just behind the girth. The horse should continue to move on the circle to the right, but should also be moving outward from the center of the circle at the same time. The horse increases the size of the circle by yielding away from the rider’s leg. At no time should the horse change his initial bend. He should yield to the rider’s leg while maintaining his position.

Leg yielding is an excellent way to increase the horse’s suppleness.

Notice in the following picture how slight the bend is when performing the leg yield in a straight line.

A lot of trainers use leg yielding as a preliminary exercise to other lateral movements. I agree with this use of leg yielding, but I believe it can be an extremely effective exercise on its own and should be used frequently for its value in making the horse more supple and compliant. Anytime you are working at any gait, walk, jog or lope, ask the horse to leg yield and expect a correct response. It is not necessary for the horse to move a great distance, but it is necessary that he mold himself around your leg and move away from the pressure while continuing the initial exercise.

The advanced shoulder-in, travers (haunches in) and renvers (haunches out) are not as difficult for the supple horse as they are for the rider. A correct performance requires very subtle and accurate cues by a rider who has gained control over his own body and instantly recognizes the responses of his horse.

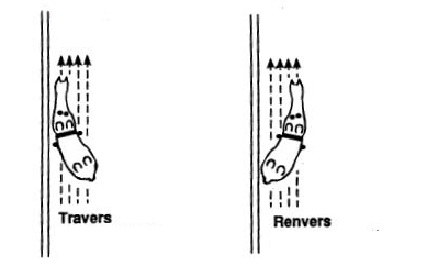

The terms "in" and "out" always refer to the center of any circle. If the horse is moving to the left to any degree, then the center of the circle is to the left. The travers, therefore, requires the haunches to be moved to the left, while the renvers requires the haunches to be moved to the right. In an arena, the center of the arena is always "in" and the rail is always "out."

SHOULDER-IN

Shoulder-in is an advanced performance, and it is the most effective exercise for improving suppleness. For horses, which have not yet mastered the shoulder-in, lateral work of any kind is a beneficial beginning.

A shoulder-in exercise requires the horse to move his forehead exactly the width of his chest to the inside of the circle, thus creating a three-track movement. If the horse is performing a shoulder-in while moving to the left, the shoulder will move enough to the left to allow the right foreleg to track directly in front of the left hind foot. The three tracks then become the left forefoot, the right forefoot and left hind foot, and then the right hind foot.

When the shoulder is moved to the inside, the horse’s neck should show only moderate increased bending.

In the shoulder-in, the horse must move his head,

neck and shoulders the width of this body toward the center of the circle while

the horse’s hindquarters remain straight.

The cues for the shoulder-in, while moving to the left, are light indirect rein pressure against the horse’s neck on the right side. (If you are riding with two hands, in addition to indirect rein, you can also shorten the inside rein [direct rein] to assist the horse in moving to the new position.) The rider should then apply light right leg pressure in front of the girth to move the horse’s shoulder to the inside. At the same time, the rider must establish a holding leg pressure on the left side behind the girth to keep the horse’s hindquarters tracking straight.

The rider must maintain his weight in the middle of his horse, his spine being directly in line with that of the horse’s spine.

When shoulder-in is performed correctly, the horse will move his shoulder toward the center of the circle exactly the width of this chest, establishing the three separate hoof placement tracks. The left forefoot creates the inside track. The right forefoot tracks directly in front of the left hind foot making the second track. The third track, or outside track, is the right hind foot.

When first practicing the shoulder-in the rider will find there is often a tendency to exert too much leg or rein pressure in an attempt to force the horse to move into position.

Generally, the horse will respond by starting to circle rather than continuing in a straight line. If the horse begins to circle, the rider will have to soften the rein cue and move the inside leg cue forward to retard the circling action of the horse’s forehand. If the hindquarters show swing away from the inside leg pressure instead of being held by it, the rider will have to correct the horse’s position by moving the outside leg cue back toward the horse’s flank. Sometimes the horse will let his hindquarters swing out, away from the rider’s inside leg pressure. The rider may find it necessary to make any number of compensating cue adjustments to keep the horse in the three-track position.

During the learning period, the rider may have to continue the compensating cues for some time until the horse both understands the exercise and is physically able (supple enough) to perform it properly. It must be kept in mind that the shoulder-in, travers, and renvers require the horse to arch his body. The horse’s spine is actually too rigid to arch, so it is the suppleness of the body, which allows the horse to move the forehand or the hindquarters separately. This flexion is difficult for the horse to hold, and he must be well-conditioned. When the horse is physically able to do the exercise, and understands what is being asked, it is the same lateral flexion which tells the rider the performance is correct.

The rider should always begin every request with the lightest possible cue, increasing the pressure of the cue until there is a response. Each time an exercise is requested, the rider begins with the minimal cue, following it with a little more severe one, and then a more aggressive cue until the horse makes an attempt to perform. As both members of the team gain a greater understanding of their respective responsibilities, the cues become more subtle.

Special Training Tip: If you want your horse to break at the withers, holding his head and neck down instead of arched and up, try an exaggerated “shoulder-in”.

When doing a traditional shoulder-in, the rider moves the horse’s head and neck toward the center of the arena while also pushing the shoulder over just enough to cause the outside front foot to track in front of the inside hind hoof. To correctly accomplish the shoulder-in the horse must move the forehand over just the width of his chest.

When done correctly, the hoof prints will leave three tracks…the outside hind hoof leaves a track, the outside front hoof in front of the inside hind hoof leave a second track, and the inside front hoof leaves a track of its own. Click here to see picture.

Flat saddle riders use the shoulder-in to create a supple, flexible, yielding horse. (Western riders do also.)

For western riders, an exaggerated shoulder-in, if held for several minutes while traveling at any gait, will cause the horse to want to straighten and lower his neck. Don’t hold the bend so long that the horse begins to be uncomfortable and fuss, but hold long enough for the horse to want to straighten his neck.

As soon as you let the horse straighten his neck, praise him lavishly. Ride with the neck in the straight, lowered position until the horse begins to lose his frame, then repeat the exercise. Always work both directions, always give plenty of praise when the horse lowers his head and neck, and work all three gaits.

TRAVERS

The travers (haunches-in) is accomplished by the rider maintaining his weight in the middle of the horse, cueing with the outside leg back toward the flank, bringing the inside leg forward toward the girth to hold the forehand straight, and applying light direct rein of opposition to fix the bit so the horse does not bend his neck.

In the past the travers was described as having three tracks. But recently the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI), the international governing body for equestrian sport, and the U.S. Equestrian Federation (USEF) changed the definition. Now travers is to be ridden as a four-track movement at approximately a 35-degree angle. (Remember shoulder-in is ridden on three tracks with approximately a 30-degree angle.) Dressage judges feel this makes much more sense as the horse’s body in travers (and consequently the half pass) should have more bend than it does in a shoulder-in.

The rider will experience the same exaggerated reaction to the new exercise (travers) from the novice horse, and again, must adjust the cues to compensate for the horse’s inexperience. If the forehand gets out of position, the rider must change one or the other of his cues to bring the forehand back to the center. If the hindquarters fail to move over the prescribed distance, the rider may have to bump the hindquarters over by application of increased leg pressure.

RENVERS

The renvers is simply the reverse of the travers, and the rider’s leg cues will be just the opposite of the travers cues when the horse is moving in the same direction.

Once the horse has gained the needed suppleness to perform these lateral exercise, the rider will be able to exert independent control over the horse’s forehand and hindquarters at will, and the response of the horse will always be fluid and smooth.

Assignment:

Performing the

exercises in the lesson takes time – please do not rush your horse, allow him

time to learn what you are asking. Give

him the time to get in condition. You

will not be able to read the lesson and do the assignment in one training

session (unless your horse is already advanced). Make a commitment to work with

your horse every day, even if it is just for a few minutes. Do not drill and

drill, short successful lessons are more beneficial than long frustrating

training sessions.

Please send videos of you teaching your horse

to:

1. Two-track/half pass

2. Leg yield

Continue to work

on these two exercises. In the next lesson your horse will need to be able to

perform the half pass, as it is the basis for a flying lead change.

Once your

horse has mastered these two exercises, you may advance to the more difficult

maneuvers. Do not move on to the

shoulder-in, travers and renvers

until you horse is comfortable with two-tracking and leg yielding.

You

may post the videos to a video hosting web site; for example: YouTube. Please send the link to cathyhansonqh@gmail.com