SCULPT

YOUR HORSE

Deanna Cummins

Copyright©2011

Lesson Five

Medium

and Application

In this lesson you will learn the

differences between working with clay and other traditional mediums such as

stone and wood. (Medium: a commonly used word in the art world which means

material and work of production.) We will briefly examine the process of using

material other than clay. Finally,

you’ll learn to properly apply your clay to the armature.

Different clay and

medium options

There are several mediums to work with

when sculpting. The two traditional

mediums are wood and stone.

Different mediums require different

techniques such as carving away or adding material. Throughout this course you will learn the

technique of adding, but will have the opportunity to briefly learn about

carving, as well as some other artistic practices.

There is a wide variety of clays

available to the artist. Clays can be chosen by texture or consistency.

Depending on an artist’s style and subject she may choose more or less firm

clay. Firm and soft clays range from ceramic, which is soft when it is

hydrated, to Plasticine clay which has three types of

consistencies, but is still very firm when compared to ceramic. Just like clay,

wood and stone have many consistencies as well. Depending on the location of

the wood it will be more or less firm. For example, redwood is soft do to the

climate of its location. Walnut is a firm wood because it grows in dryer

climates. This is also true with stone material. One very commonly used stone

is marble. It is often chosen for its more forgiving nature; it’s easy to sand

and make smooth.

Clay Versus Other Mediums

Clay

Clay

allows an artist to shape, add and carve away from the artwork. With its

flexibility, an artist can easily make adjustments throughout the sculpting process.

When clay is finished it will always need a curing process to make it last.

This is done in a number of ways depending on the desired finish.

Ceramic

First and most commonly known is the firing

of ceramic. To make this clay durable it will need to be brushed with a glaze

and fired in a kiln at an approximate temperature of 1700 and 2000

degrees.

Air drying clay

Air drying clay is not long lasting,

but is often used by the enthusiast because of its low maintenance and easy

hardening. Air drying clay can be

painted and made to look very attractive.

Non-drying clays

Non-drying clays will always need to be

taken through a mold process. There are

a number of processes for hardening, and each process leads to a different

finish.

Lost wax

The process of lost wax begins with a

rubber mold around the clay figure. This mold captures the detail, creating a

negative inside the mold. Once the mold cures, the clay figure is pulled out of

the rubber mold and wax is poured in. This creates the second positive of the

sculpture in wax.

The wax is then dipped into ceramic. This

creates another mold around the figure capturing the detail. This mold is fired

as the wax is melted out. This is the second negative. When the hot mold is

taken out of the firing oven the metal is poured in to create the finale

sculpture in “positive” form. The metals often used for casting sculptures are

bronze, pewter, aluminum, copper and brass. To finish a metal, the artist will

always need to cover it with a protecting agency. This is the color you see on

many sculptures, called patina.

Resin

In this process a rubber mold is

created around the sculpture. This is the same process as the lost wax rubber

mold. After the clay is pulled from the mold, two agencies are mixed together

to create a curing process. Before this process is able to reach its final

hardening state, it is poured into the mold creating a resin cast of the

original.

Wood

When

sculpting with wood, an artist is essentially carving away to create the image.

Stone

Stone

is a material that an artist will have to carve to create a shape. Like wood,

it is, of course, possible to add pieces to a sculpture. (Many large sculptures

are made up of many smaller parts and bolted together, or in the case of wood,

put together with dowels.) Even the

pieces need to be carved to create the desired shape to complete the work.

Metal

This

will require an artist to weld the pieces together and grind (carve) away. By

bending and shaping the pieces an artist is able to sculpt directly in the

metal unlike the other processes involving metal.

Measuring Armature for

Body and Leg Proportions

Body proportions

This is where you determine whether your armature is properly

proportioned or if it will be necessary to make adjustments.

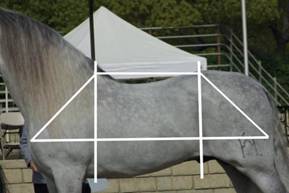

1. Start by checking the torso as

explained in lesson 4. The wire torso

should measure close to half the height of your future sculpture. For example,

if your sculpture is

Find similarities in the measurements

of the different parts of the horse’s body. Measure the angle of the shoulder

and compare that with the angle of the hip. Measure the length of the bottom

line and compare that with the back. When

you are doing these measurements be sure you have a

set point to measure from. For example, if you are measuring the bottom line,

always start at the base of the triceps and end at the patellar bone of the

gaskin or the middle of the flank. Having these points of reference will help

you measure more accurately on your horse and sculpture. Choose defined areas

as your measurement points.

2. The armature should have extra

length for the legs. You will trim the excess wire after the clay has been

added.

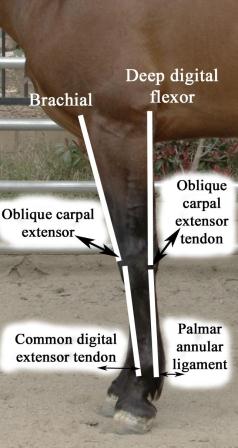

To determine the proportions, measure

the upper forearm from the top of the brachial muscle to the oblique carpal

extensor muscle. Compare this measurement with the lower leg measured from the

oblique carpal extensor muscle to the common digital extensor tendon. Measure

the length of the back of the upper arm from the deep digital flexor to the

oblique carpal extensor tendon. Also measure the lower leg from the oblique

carpal extensor tendon to the palmar annular

ligament. Notice how these lengths are the same on the front of the leg and the

back. Your lower leg measurements should be the same length as should your

upper leg measurements.

Mark your wire with a permanent marker

on these points. Then mark from the fetlock to the toe of the hoof. These marks

are merely a guide to help you place your clay generally in the correct

area.

Note: The leg and neck

measurements are all the same length. Though the hind leg looks longer due to the

gaskin joint it is a trick of the eye. Notice the line running from elbow to

gaskin; these two joints are at the same height.

3. You will also want extra length for

the head and neck. This is because you will be manipulating the wire to the

desired position later which changes the wire’s position inside the clay. For

this reason it is necessary to have extra length to avoid difficulty later.

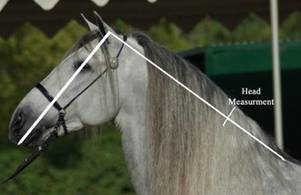

Proportions of the neck are measured in

relation to the length of the horse’s back. The horse’s topline

extends from his poll to the top (dock) of his tail (see picture below).

Measure the “original” horse between the withers and the dock of the tail, then

using this length, measure the neck starting from the withers ending at or near

the poll.

The length of the neck and the back

should be very similar. Measure them on the wire frame and mark each point with

a permanent marker. On your sculpture, always keep these measurements matching

the “original” as this will keep your sculpture in the proper proportions.

4. The head should be one-half to

three-quarters the length of the neck. Measure the head from the poll to the

top lip. Then compare this measurement with the neck. Keep

extra length in your armature. You will trim this after your clay has been

fully added.

Applying the Clay to

the Armature

In

lesson 4 you learned to build your armature, so now your wire armature properly

prepared with tinfoil and bent into the desired position. In lesson 1 you where

asked to send a photograph of your expected composition. That expected

composition should be your reference now for your sculpture’s position.

The

first steps of clay application do not require any detail. We will discuss the

process according to the ideal conformation broken down into parts of the

horse. In order to create a portrait of your horse you will have to assess what

is different in your horse’s conformation and make the necessary adjustments.

Before beginning you will want to

soften your clay.

For very firm clay you can soften it by

merely needing it in your hands and between your fingers. If you find it

particularly hard or cold increase the temperature in your work room to help

heat the clay. You may also add a small

amount of vegetable oil to your clay if it is cracking. I prefer to save this

as a last resort only for the reason that it can cause sculpting to be more

difficult and the clay will sometimes have a hard time holding the detail.

Though it is an option and some sculptors find it useful.

Important Tips Before Beginning!

You will want to be sure that your

layers are always smooth and flat before adding the next layer. The reason for

this is to prevent air inside your figure. If you have large air pockets they

may burst as the clay shrinks and hardens in the oven.

Rotate your sculpture as you add the

clay to make sure that your horse’s body is even when viewed from the front,

back, above, underneath and on the right and left.

A.

Barrel

Begin by applying clay in layers on top

of the tinfoil to the torso of the armature. The barrel of the horse should be even

on both sides. But not too round. Though this part of the horse may look like a

large ball it still has some areas that are ever so slightly flat or less

curved.

Once the clay is at least 2-4 inches

thick on the barrel, begin to work on the haunches. Each time you add a layer to your sculpture,

refer to your horse’s photo and ask yourself, “Does it look like my horse or do

I need to make changes?”

See

video link http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CyUpLp76Vak&feature=related

B. Haunches and shoulders

You

may begin with the shoulders or haunches. It will not make a difference in your

sculpture’s finished look or overall structure.

You will be applying the clay in

layered shapes. These shapes should compliment the basic shapes of the horse’s

body part upon which you are working.

As you apply the clay for the haunches,

remember the basic shapes in lesson 2. Ask yourself, “How many basic shapes are

in the haunches?” Look at the anatomy of

the horse from different angles. When you view the horse from the front, the

barrel should be wide enough to prohibit any view of the haunches. When you

view it from behind you may see a slight shape of the barrel halfway down the

hip between the point of hip and the stifle. This is where the horse has a

slight concave curve. Be sure to make the haunches wide enough to cover any

other views of the barrel. Even weak haunches of a horse will be fairly large

when compared to the rest of the body.

Again ask yourself how many basic shapes make

up the shoulders? As you sculpt the two shoulders you will find that you have a

hollow cavity for the chest. We will discuss filling this cavity later. The

shoulders of a horse slope back to the withers. Therefore you are unable to see

clearly where the scapula lays on the horse when you view him from the front.

As you sight down the shoulder you will notice that it comes to a “fatty”

muscular part of the body. This is the humerus below

the point of the shoulder and above the radius of the forearm. In areas like

these add more clay to create the muscle.

Some horses will be in shape and

muscular, while others may be too fat or very slim. Be sure to keep looking at your horse’s body

type and make adjustments accordingly as you add clay.

See

video Links: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBEIaId91ts

Sculpting

the shoulder:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8snKff6no18

C. Neck and head

After

you have defined the shoulder, start adding to the neck. A horse’s neck has a

lot of definition when viewed from angles such as the top and the front. Viewing

it from the side will make it look flat with little muscle, but this is

deceiving, so keep looking around your sculpture and viewing the neck from all

sides.

Note:

Each

horse will have a neck which reveals his breed and discipline. Some horses have

thick arching necks with large crests others may be straight with little or no

arch with a thin crest. Some horse’s throatlatches are very thick and others

very refined. Study these differences and compare your horse with other horses.

It is also helpful to compare the breed conformation standards to your horse’s

conformation. This helps define your horse’s individuality.

As

you apply clay to the neck, add it in sections. Make sure you apply enough

thickness to the neck. You will always

be able to carve away too much clay during later steps. Try to sculpt the neck

with the definitions that you see in your horse. Make the base of the neck

thick and the throat thin. As you apply the clay, be sure to view it from the

top and front as well as the side. Be sure that your horse’s neck and crest are

thick enough from above. This is the

last point where you can easily change the position of the horse. So make all

the necessary adjustments now.

It

is simple to apply clay to the head area.

The most important part about the first steps in adding clay to the head

is to make sure the head is the proper length in relationship to your horse’s

neck. You are using proportions now…so 1

inch in real life may only be 1/8 on your sculpture.

Measure

the length of your horse’s head. Now

take that measurement and starting at the horse’s poll, measure down the neck

the distance of the head. Note the location on the neck where the head distance

stops and match those proportions on your sculpture.

When adding clay to the head, check the

size of the forehead in relation to the muzzle. Does the head taper to a small

refined muzzle or is the muzzle large?

Is the forehead wide between the eyes or not?

See

video link:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=09wFQ3F7_Qo

D. Forelegs

This is the time when you will

determine the proper proportion of your horse’s legs to his body (Review

proportion measurements). Anything after this will be small detail. The

legs have only two stages of sculpting: shaping and detail. Unlike the other

parts of the body which will require shaping, muscle toning and detail. The

lower legs are mainly bone and ligaments.

We will discuss the leg in three parts:

upper, lower and hoof.

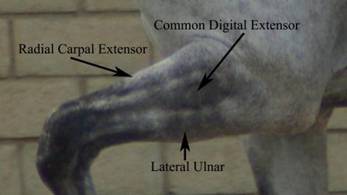

The upper leg has three visible muscles. These are Radial Carpal

Extensor located in the front between the triceps and the knee. The Common

Digital Extensor located against the Radial Carpal Extensor. And the Lateral Ulnar on the back of the leg located between the elbow and

the back of the knee. All three of these muscles are often visible on most

horses.

Sport horses will have well developed

muscles causing them to be more visible. The Radial Carpal Extensor is a muscle

which is most visible. Breeds such as stock Quarter horses will have a

naturally large Radial Carpal Extensor. All individuals vary in muscle tone and

visible structure.

Add these muscles in three parts. Shape

your clay to mimic the muscles and add them to the leg.

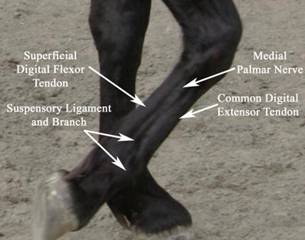

The lower leg is made up of bone,

tendons and ligaments. The lower leg has a vast number of tendons and ligaments

holding the bones in place. But the visible ones are the Common Digital

Extensor Tendon which runs down the front of the cannon and meets the Suspensory Ligament and Branch. The Suspensory

Ligament raps around the fetlock and runs up the center of the cannon, behind

the Medial Palmar Nerve.

The Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon runs up

the back of the cannon.

Add clay to the cannon without detail,

including the area for the knee. The knee will be discussed separately due to

its complexity.

Now you should have clay in the area of

the cannon. Here is where you will need to add or carve away to make the cannon

the proper proportion and thickness. Be sure to view your sculpture’s leg from

all angles particularly from the front. You want to be sure that it is even on

both sides and not too thin or thick. Refer to your “original” photographs and

compare the shapes of your sculpture to the shapes of the horse. After the clay

is smoothed and has its proper thickness you can etch these tendons, ligaments

and nerves into the leg with your tools. Detailing of the legs will be

discussed in a later lesson.

See video link:

Sculpting the foreleg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UpjdoTYmFKA

Sculpting the Hoof

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXISEeaIpco&feature=youtube_gdata

The hoof and

pastern can be shaped and then added to the leg. Do this with a small amount of

clay and roll it into a ball. Then carefully roll the top into a cylinder this

will be the pastern. Now shape the hoof. Start by flattening the walls and

pointing the toe. The hoof is wide and round at the toe. The heel is more

square and straight. The hoof should be wider then the leg when viewed from

underneath. Once you have the proper shape you can attach it to the wire which

is sticking out of the center of the cannon bone.

C. Hind legs

Before adding clay to the hind legs be sure your wire is bent in the proper joints. These joints

will be the gaskin, hock and pastern. Also check your hind leg length. This is

an area that many people believe is longer then it really is. On a properly

proportioned horse (as shown previously in this lesson) you will have the same

length in the forearm, neck and hind leg.

Note: Some horses will very in the hind leg length. This is often due to the

gaskin being to long or short (most commonly too long in many breeds). Another

possibility in the hind leg is the cannon being too long. This will cause

balancing difficulties in the rest of the body. When you find a horse that does

not conform to the ideal proportions (which many of our horses don’t) you will

want to keep these proportions the same and not alter them so that you are able

to capture the horse’s true unique beauty. Dealing with this difference in a

sculpture is quite easy. All you must do is find one part of the horse that

matches that length and match these measurements on your sculpture. Before

you proceed be sure that this is a true conformation difference your horse has

and not your own intellect distorting the real image.

To add the clay, start at the head of

the gastrocnemius; bring the clay to a mild point for

the hock. Then proceed to adding the hock joint and cannon. Add the pastern and

hoof as mentioned in the previous section about sculpting the forelegs.

See

video link:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6WhQwkX6hqc

Assignment:

1.

a. Measure the areas mentioned in this

lesson on a photo of your horse standing square. Mark the photo with the proper

measurements detailed with the point names.

b. For the parts of the horse not

measured in this lesson find your own ways of measuring and in a short essay

explain the reasons why you chose the measurement points you have. Mark them on

another photo of your horse detailed with the point names.

2.

Add the clay to your armature as described in this lesson. Send photos of all four

angles of your sculpture. Send a short video demonstrating your sculpting

techniques.

Send your assignment text, pictures and

video link to: Deanna Cummins dncummins06@yahoo.com

Please

be sure to put your full name on all work.