HORSE

PHOTOGRAPHY

Lynette Smith

LESSON THREE

Defining Exposure

• What does the term “Exposure” mean?

• Shutter Priority and Aperture Priority

• ISO – how it affects exposure

• RAW vs. Jpeg

• White Balance

What

does the term “Exposure” mean?

Basically, photography is all about light.

To

get the correct exposure for your photograph, you need to know the settings

that you can adjust and what they do. The

main players are ISO, f-stops and shutter speed.

What does "exposure of the image" mean and how

will it affect your digital camera photos?

Simply put: exposure is the

unit of measurement for the total amount of light permitted to reach the

electronic sensor during the process of taking a photograph.

If the shot is exposed too long the photograph

will be washed out because there is too much light. If the shot is

exposed for too short a period of time the photograph

will be dark because there was too little light.

Almost all cameras today

have light meters, which measure the light in the given shot and automatically

set an ideal exposure time. Most people depend on the built-in light

meter, and that is fine. But if you

know how to control your exposures, you can get some creative and often times better pictures.

Shutter

Priority and Aperture Priority

The two main controls your digital camera

uses to set exposure are the shutter speed

(how long light hits the film) and aperture (the size of the

lens opening which allows light to hit the film).

Shutter speed and aperture work together. You can get the same amount of light with a

small opening that remains open longer as you can with a large opening that is

open less time.

Shutter speeds are measured in seconds and more commonly

fractions of a second. (1/2000 of a second is very fast and 8 seconds is

extremely slow).

Shutter speed is also a way to control movement. When the shutter is open for more than a

fraction of a second and there is any movement from your subject or your

camera, the movement will cause a blur in your image.

In order to freeze the image and

get a sharp photo, you need a faster shutter speed.

In effect, the shutter

determines what image is captured on your film.

The shutter

is a small plastic “door” that opens and closes allowing light onto the film or

prevents light from reaching the film. The shutter is opened when you press the

shutter release button on your camera.

The shutter speed determines how long the shutter remains open.

A shutter speed time in

typical everyday photography is about 1/250th of a second. If the shutter stayed open for 1/100th of a second then you have almost twice as much light coming

in. If the shutter stays open for

1/500th of a second only half as much light comes in.

Shutter speeds can be as fast as 1/8000th of a second. The faster the shutter speeds, the more you

freeze the action of a moment. Click

here to see an example of pictures showing shutter speeds.

Slower shutter speeds are

often selected to suggest movement in a still photograph of a moving

subject. Excessively fast shutter speeds

can cause a moving subject to appear unnaturally frozen. For instance, a cantering

horse may be caught with all feet in the air and all indication of movement

lost in the frozen moment.

If you are photographing

fast moving objects such as cantering horses, you need to select fast shutter

speeds to capture the sharpest picture you can if that’s the effect you’re

looking for. Or you can choose a slower

shutter speed--a longer amount of time for light to enter--that can introduce

an element of blur to the subject creating a different image.

A

good rule of thumb is to have a shutter speed that is twice your focal

length. If you’re using a 200mm lens,

your shutter speed shouldn’t be slower than 400.

There are creative times

when you want to take an action picture with a slower shutter speed to

emphasize the action by allowing the picture to blur. (Example: the bottom

picture above.)

There are also times you

may want to stop the action and freeze the subject so that it is crystal clear.

Apertures are measured in what is referred to as f/stops (a

very wide aperture is f/2.8 and a very small aperture is f/19). Your shutter speed and aperture settings need

to be balanced in order to provide a proper exposure

to any photograph.

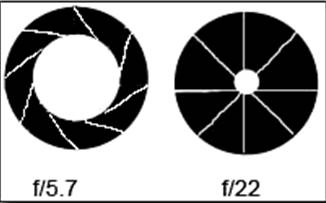

This can seem puzzling, but it isn’t if you keep in mind

the higher the aperture number the smaller the aperture is. For instance f/22 is

a very small aperture setting meaning a very small hole in the lens’

barrel. f/5.7 is a

quite large aperture setting creating a fairly large

hole in the lens’ barrel. The smaller numbers let in more light.

F-stops can be a somewhat

confusing in the beginning because the numbers do not work the way you would

expect. For instance, a higher f-stop

number indicates a smaller aperture diameter -- in other words, as the iris

opening decreases in size the f-stop number increases. A lower f-stop number indicates a larger

aperture diameter therefore the iris opening increases in size and the f-stop

number decreases.

F-stop settings are normally written with a forward slash

such as: f/16. Common f-stops you will hear referenced are: f/1.4, f/2,

f/2.8, f/4, f/5.7, f/8, f/11, f/16, and f/22.

Note:

A small f-stop (large aperture) results in a small depth of field and a

larger f-stop (smaller aperture) gives a large depth of field.

Your f/stop

is determined by the lens, not the

camera.

Depending

on the lens you have on your camera body, you will have a range of f/stops

available to you.

Practice

saying this to yourself: large aperture

numbers mean small opening in my lens, therefore less light. Smaller numbers mean a larger opening

allowing more light.

f/5.7 – large aperture (lets

in more light)

f/22 – smaller aperture (lets

in less light)

F-stop and aperture are definitely the

most complicated and confusing aspects to exposure control

and composition. Here’s a good rule of thumb.

Use a

small number f-stop (large aperture) for portraits so you get your subject in

focus in a small depth of field; you aren’t concerned about the

background. Ex: Small F-Stop = Small

Depth of Field = Less Light Needed

Use a

large number f-stop (small aperture) to maximize the amount of background in

focus. Ex: Large F-Stop = Large

Depth of Field = More Light Needed

A standard

“Kit” lens typically comes with an 18-55mm with a range of

f/4 to f/5.6. Meaning that at 18mm (zoomed all the way out) you can go as low

as f/4, and at 55mm (zoomed all the way in) you can go as low as f/5.6. Typically, the lower the f/stop on your

camera the more expensive the lens will be.

Along with letting more or less light into the camera, the size of the aperture

governs the 'Depth of Field'. Depth of field

is the range of distance in which the subject is acceptably sharp. A

smaller aperture will give you a greater depth of field and a larger aperture

will give you a more restricted depth of field.

If you are photographing

vast landscapes, horses in a field on a sunny day, the chances are that

everything will be in focus and you will not notice

this occurrence at all. Depth of field is much more noticeable when taking

close-up shots, such as portraits or headshots of horses.

It is often attractive to

have the background of your picture out of focus. This is easy to achieve by

selecting a larger aperture to restrict the depth of field. For example, f/2.8 gives less depth of field,

while a smaller aperture like f/16 provides a greater area from front to back,

giving good definition to details.

A wide-angle lens will

give you almost limitless depth of field.

ISO

– how it affects exposure

The third item that

affects proper exposure is the speed of the film referred to as the ISO

number. ISO stands for 'International

Organization for Standardization'.

The film speed ratings

are used to signify the relative amount of light necessary to provide a proper

exposure. ISO settings determine how

sensitive your camera is to light. When

you shoot at a lower ISO (less sensitive), you get better quality images with

less of the “digital noise”. However,

when shooting at a higher ISO (more sensitive), you can capture stop-action

(fast-moving) shots better, like a gaming event, jumping or roping.

When

shooting at lower ISO’s you must use lower numbered f-stops (i.e. f/2.8) and

slower shutter speeds. Meaning, you lose

depth of field and increase chance of blur.

On the other hand, when shooting at higher ISO, you will tend to lose

some detail and increase the amount of noise in your image.

On a digital camera the

ISO setting is built into the camera.

Until digital, the only way to change the ISO setting was to swap out

the film. With a digital camera changing

the ISO is as simple as changing a setting internally in your camera.

When working with film,

the more sensitive it is to light the faster the film and the higher the ISO

number will be. What that means is it

takes less light to expose film with an ISO rating of 400 (exposes faster) and

will require more light to expose film with an ISO

rating of 100 (exposes slower).

How does all this effect digital cameras?

In the digital photography world the phenomenon

is called 'noise' not 'grain', the cause of the problem is slightly different.

Grain is a film issue. Noise is a digital issue. "Grain" refers to

the maximum resolving power of film. It is a literal term; film is sensitive to

light because it contains tiny grains of silver halide, which change when they

are exposed to light. Smaller grains of silver halide mean higher image

sharpness, but also lower light sensitivity. The more sensitive a film is, all

other things being equal, the more grainy the image

is, because the larger the grains of silver halide.

Digital cameras do not

have grain by definition; they do not use grains of silver halide. They do have

noise--unwanted analog noise from the sensor.

When light levels are low, the sensor has trouble reading the scene

properly and pixels of random color are thrown into the picture.

The 'better' digital

cameras have, usually hidden away among the manual settings, a sort of

simulation of the film speed effect. My camera for instance, a Canon EOS 40D,

has an ISO range from 100 to 3200. This feature is not available in fully auto mode, but is available in all the other modes. When I’m shooting fast action, like a horse

cantering, I may choose ISO 400 or 800.

If the light isn’t great because we are working inside an indoor arena,

I may shoot at ISO 1600, which offers more light. Click here to

see ISO examples.

You’ll really notice the

difference when it’s magnified at 100% zoom, but at a normal size image the different is more difficult to see.

I realize talking about

ISOs, shutter speeds, apertures and more can be very confusing. However, it is important that you master the

concepts since they are all interrelated.

The significance of each one and how it affects your equine photography

will become more noticeable as you gain more experience.

RAW Images vs. JPEG Images: What’s

the Difference?

A frequent question from both

experienced photographers and those just beginning in digital is: should I shoot

in RAW or JPEG format with a digital SLR (dSLR)

camera?

RAW

images are uncompressed digital photos that save image data precisely the way

the image was captured by the camera's sensor.

When you’re shooting in RAW mode, the exposure and color temperature

settings (i.e. white balance) are not applied to the image and the photo is

saved in an uncompressed format. The resulting image is called a raw image

file.

Using

“conversion software” you can adjust the image sharpness, contrast, tone and color, add filters, adjust the white balance,

adjust the exposure by two stops either direction and choose which format and

resolution you want the file when saved.

If you

shoot in JPG format, once the image is taken, aside from the post processing in

Photoshop, you are very limited with what you can do to 'fix' any problems that

may arise.

RAW files hold all the

RAW data captured by the camera. Unlike conventional photography where light is

exposed against film with a specific chemical formulation to provide deep

saturation or soft skin tones that would otherwise be automatically applied

based on the type of film used, RAW digital files contain raw data that is not

interpreted and is unaltered. RAW files

in their simplest description can be thought of as digital negatives. They are

a pre-production starting point.

Since

raw images are not compressed, they take up considerably more disk space than a

JPEG file format. The file size will be

about twice as large. With raw images,

the original image detail is not compromised by image compression resulting in

a higher quality than JPEG images. Your typical user may not notice the

difference in image quality; your professional photographer typically will

shoot in RAW mode to maintain the best quality for each image.

To give you an idea of file size, when shooting

in JPG mode on a 4 Gig card you can end up taking approximately 800 plus

photos. When shooting in RAW mode on a 4 gig card you will end up with approximately 340

images. If you shoot in RAW mode and

discover you’re almost out of memory with no cards left, you can switch your

camera into JPG mode and it will provide more room on

the card. The initial images will be RAW

and anything after you switched would be JPG.

Keep

file size in mind, because it’s easy to fill cards

quickly at a horse show.

Cameras

made by different manufacturers save RAW images in different file formats. Here is a list of common RAW image file

formats used by various digital camera manufacturers.

·

Adobe – DNG

·

Canon – CR2 & CRW

·

Fuji – RAF

·

Kodak – DCR

·

Minolta – MRW

·

Nikon – NEF

·

Olympus – ORF

·

Pentax – PEF

·

Sony - SRF

Keeping

track of the various RAW formats can be challenging, however, most

image-editing programs such as Adobe Photoshop CS support most raw image

files.

JPEG (Joint

Photographic Experts Group) is a “lossy” compression technique for color pictures pronounced, "jay-peg". Lossy means "with

losses" to image quality. JPG compression has very high efficiency

(relatively tiny files) because it is intentionally designed to be lossy,

designed to give very small files without the requirement for full

recoverability. JPEG format compresses

image data into a smaller file size. A

JPEG file contains less data (how much depends on the specified size and

compression/quality settings) than an equivalent RAW file,

but is able to closely reproduce an image once fully loaded.

When

saving an image with photo editing software it is possible to save an image

with different levels of JPEG compression. This enables you to create files

that take less storage space sacrificing how well the file displays,

or take up more storage space to more accurately reproduce the original

image.

The Pros of

RAW format:

·

RAW is a digital negative capturing all the data from

your camera providing a foundational element where you can apply all of your edits without sacrificing image quality.

·

RAW file software editors allow you to quickly and easily change the output of your image such as

adjusting exposure, white balance, noise reduction, image size, saturation,

contrast, levels, curves, sharpness, output resolution, bits/channel, etc.

·

RAW file software editors allow you to load saved

adjustment settings and some even enable users to

batch process a group of files versus making changes to one file at a time.

·

The Cons of

RAW format:

·

RAW files take up a lot more space on your camera's

compact flash card or micro drive than other formats. JPG images on a 4 – gig card result in about

800 photos whereas RAW files on a 4-gig card decrease to approximately 340

images.

·

RAW files require you perform some amount of post

processing using photo editing software to convert your image to an editable

file type for editing, printing and/or online display.

·

RAW file software editors have a learning curve, and can be intimidating.

·

RAW files essentially contain more data and take

longer to open and process than a JPEG or a TIFF File.

The Pros of

JPEG format:

·

JPEG is a file format that has been adopted as a

standard and can be loaded in a variety of programs for easy and simple

display.

·

Most common format for uploading to a website gallery.

·

JPEG files take up less space on your camera's compact

flash card or microdrive than other formats.

·

JPEGs can be loaded easily by most all image editing

software programs.

·

Most dSLRs enable you to

choose what size JPEG files (S, M, or L) to save to your compact flash card or microdrive when shooting. This enables you to use smaller

images that are easier to handle for email attachments, web display or as an

alternate preview mechanism if your camera supports saving files in JPEG and

RAW formats simultaneously.

The Cons of

JPEG format:

·

JPEGs are not a loss-less file format. Each time the

file is saved data is compressed, with some data being lost in the process. The

net impact can be loss of color saturation, color range and sharpness.

·

Degrade (lose image quality) each time they’re

compressed and transferred. Compression

reduces the file size at the expense of discarding information about the image

itself.

·

Not the best format for printing gallery-quality

prints.

Which Format

Is The Better Format To Use?

It boils down to personal

choice and matching up the pros and cons to your photographic needs and

style. Some photographers feel more

strongly about one.

I shoot RAW images

because I like the creative flexibility and the high quality the image

provides. RAW files are typically the

preferred file type for producing an “art” photograph with a digital camera. The reason being you can adjust the color and

tonality more efficiently with better results than you can with a JPEG or TIFF

file.

Another great reason for

shooting RAW: sometimes you forget to check your settings and errors

occur. RAW images allow you more

flexibility to correct for errors made while shooting the event. RAW files have saved me by allowing me to

really edit the image to a more accurate version of the event I was shooting.

White Balance Indoors and Outdoors

Indoor and outdoor light

is much different and can give your photograph an

entirely different hue. Most digital

cameras offer a setting to adjust the problem referred to as “white

balance”. The function of white balance

is to find a reference point for what is “white” and then to correct offbeat

hues based on your reference point while you shoot.

Most film cameras have no

white balance setting, so you have to deal with brown/tanish tones indoors and blue tones outdoors. You will find most digital cameras have a

manual setting for white balance that will ensure the best results.

When setting white

balance, depending on your camera, you could have 3 -8 different options

available. Auto,

is typically the default setting where the camera will automatically set the

white balance when you take the photo.

Daylight is great for

natural lighting where you have all sun and no artificial light coming into

your photo. Some cameras have an

“Indoor” setting while others divide the “indoor” setting into types of light,

such as tungsten or fluorescent.

If you shoot in RAW, and

the light balance was in “Auto” and you don’t like the result, you can change

the light balance option post-processing.

When you’re taking photos

in an indoor arena without a flash, you have less light. You can compensate for this without using a

flash by adjusting your camera’s ISO speed.

In an indoor arena, my

ISO is typically set at 1600 to make sure that I’m getting the shot.

Some trial

and error adjustments will be needed based on your specific camera and

lens. You’ll have the options

of changing the shutter, aperture and ISO.

When working indoors your

“white balance” will be set for inside lighting. Be sure you change the setting if your

subjects move outdoors. A failure to

change the setting may leave you with “no” images.

Now that the technical

information is out of the way, we’ll move forward in the next lesson to learn

more about photographing the horse, horse events and more!

Assignment:

In a detailed report:

1. Tell me the camera you are using and what lens (f/5.6 etc).

2. If you have the opportunity to photograph in an indoor horse arena,

take a few photos at different ISOs, shutter speeds and aperture’s. If you cannot get to an indoor arena, take

some photos of pets inside a house or building.

3. Take some photographs of horses using different ISOs, shutter speeds

and apertures outdoors.

4. Compare the differences between how your camera is set up for indoor

shots and outdoor shots. Tell me what

you discovered.

5. Submit your best photo from indoors and outdoors with the settings

you used for each.

Please send your assignment and pictures to info@lynettesmith.com