The Business of Making Money with Horses

By Don Blazer, taught by

Eleanor Blazer

Lesson

Two

Know exactly what you are buying.

There are many breeds of horses. As reported earlier, there are at least 142

active breed registries in the

If you are already committed to a

certain breed, fine. Stick

to it. That breed can undoubtedly

make you a great deal of money, and richer still in other ways. The price of Arabians once soared as if by

magic. Maybe it was. It is not the same today, but there is still

plenty of profit in Arabians. Morgans are on a popularity roll. Peruvian Paso imports and resale prices

staggered the imagination a few years ago.

Trakehners and warmbloods (imports of almost

any kind) are very hot.

Opportunities abound!

Select any breed, and by following

the advice outlined for most facets of the horse business under consideration,

you’ll make plenty of money.

However, it would be nearly

impossible to gather and compile recent statistics for each breed, since the

data is overwhelming. Therefore,

for the purposes of this course, and because I follow my own good advice (go

where the money and information are most plentiful), I will use race horse

(Quarter Horse and Thoroughbred) statistics most often. This doesn’t mean there aren’t other racing

horses. Standardbreds are a very big

business indeed. Appaloosas are running,

and so are Paints, Arabians and mules. And this does not mean this course pertains only to race horses. You choose the breed; the rules for making

money with horses remain the same.

But as much as you might like

a non-racing or other breed, and as much as you might wish it weren’t true, it

is true—the greatest flow of cash is in Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses. These two breeds command huge prices as race

horses. In addition, they are extremely

popular as show horses, trail horses and sport horses.

I deal in Thoroughbreds and Quarter

Horses because I like lots of money, and I like it fast, and I like it easy!

The greatest number

of public and private sales are for Thoroughbreds and Quarter

Horses. The largest racing purses are

for Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses.

The biggest prizes are for jumpers, cutting horses, reining and western

pleasure futurity horses, all dominated by Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses.

A word to the wise. Horses can make you a lot of money, and

always a lot faster when you ride them among the high rollers and free

spenders. (No matter

what breed or facet of the business you choose, never think cheap! The money is there, ask for it.)

I said you must choose the breed you

like best. So don’t despair. If you choose to stick with any breed other

than a Thoroughbred or Quarter Horse, the game—except for racing—is the same.

There is plenty of money to

be made buying and selling weanlings of any breed. There is money to be made owning and standing

a stallion of any breed. There is money

to be made owning and breeding broodmares of any breed. There is money to be make training horses of

any breed. There are riches to be made

trading all breeds.

The information offered in the

following lessons is as applicable to one breed as it is to another. So stick with what you like best; you’ll be

happier, therefore, eventually richer.

From this point forward, the

statistics, the figures, the dollar amounts, the samples all pertain to

Thoroughbreds or Quarter Horses because they are the easiest statistics to

gather and the easiest to verify. (As I

told you before, there are no made up examples in the course; you can check the

accuracy of the figures if you’ve a mind to.)

As long as the discussion is not about racing, you need simply make a

mental conversion from Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses to the breed you’ve

chosen.

Inevitably

Before you can buy and sell horses

wisely, you must fully understand that POTENTIAL is

the only thing which makes a horse valuable.

The potential to make money by winning purses, the potential joy of

winning horse shows, or simply the potential for pleasure found in owning a

horse; that is what buyers buy.

Absolute nothing other than potential

is important if horses are going to make you money.

Once you have decided to concentrate

your efforts on a particular breed, you will want to become knowledgeable about

the bloodlines, events, activities and sales associated with that breed. You must know what is “hot” and what is “not”

within the breed industry. You must know

the factors which create “potential.”

After the horse’s “eye-appeal”, the

most important tool for recognizing a horse’s potential to make money is THE CATALOG.

Every registered or purebred horse,

even if he is standing in a backyard in some out-of-the-way place, has a

“catalog page.” The catalog page reports

all the facts about the horse’s family and accomplishments in a particular

way. It is your responsibility to

understand the meaning, the sizzle, the weaknesses and the strengths indicated

by the information on that page. You, and you alone, must assess the page and make the final

decision on the horse’s potential to make you money. The people who make money can read “Money” in

the catalog page.

The more you know about a catalog

page and the more information on that page, the better the chances your

decision will be profitable.

If you are buying a horse from a private

party, and no catalog page is offered, it is your responsibility to contact the

breed registry and dig out the needed information, then construct your own

catalog page for appraisal and later sales material. Do not buy until you have constructed a

catalog page. In some cases, an offered

catalog page may only be a sentence or two about the horse’s training or

talents. That is not enough. Only by knowing all about the horse’s

pedigree can you determine all the potential areas for profit. And don’t trust a catalog page which can’t be

verified. You can’t verify the

statement: “a sound gelding which will make anyone a wonderful trail

horse.” What you want to see is a list

of accomplishments—such as—won the All Around

Championship, Western World Show, 2002.

Before you buy any horse as part of

your businesses, construct a catalog page so you know exactly what potential

you are purchasing.

If you don’t construct a catalog page

for every horse you purchase, you’ll be missing opportunities to make sales,

which means missed opportunities to make money.

If you don’t construct a catalog page for every horse you purchase,

you’ll be missing opportunities to make sales, which means missed opportunities

to make money. If you don’t construct a

catalog page for every horse you buy or own, don’t blame me for your

losses. It takes

time, but you must develop a catalog page for every horse you buy and every

horse you plan to sell.

While there is nothing wrong with

buying a horse from a ranch or breeding farm, there is usually a greater margin

for profit when purchasing the horse through a sale. For one thing, it is much less costly to you

to have a number of horses to choose from in a central location. Second, you have no personal expense in

constructing a catalog page. Third, you

must be more astute when buying privately, since you are relying entirely on

your own knowledge and judgment. Most

owners and breeders overestimate the value of their horses, and consequently

ask more for them than they would bring at a sale. At a sale, you also have the consensus of

opinion to back up your appraisal, and that is a major plus. Seldom will 20 or more other professional

horsemen overbid a horse. When the

bidding stops, that’s about what the horse is worth.

Approximately 20 per cent of the

foals born each year, as well as many older horses, are sold at auction through

sales sponsored by private parties, racing associations, breeder associations,

individual breeders, show organizers or companies exclusively in the horse sale

business.

While horses purchased in sales do

not necessarily perform any better than those not in sales, you do have

advantages by purchasing at auction.

Many of the sales are “select.” Select sales require the horses being offered

to have been inspected for conformation and/or to meet some established

criteria before acceptance. There are

special sales for all breeds and for various performance talents. In the case of some yearling sales, the term

“select” is almost a guarantee you won’t get a bad horse. But it is also practically a guarantee you

will have to pay an inflated price. Why

do “select” sales create higher prices?

Because the term “select” says “more potential,” and potential is what

buyers buy.

Don’t be afraid of the price of a

horse with potential. A high-priced

horse with potential will resell at a still higher price,

and a greater profit for you.

For the best profit

margins, it is best to buy at sales and sell privately.

Catalogs are usually available

several weeks prior to the sale date.

You should obtain your catalog and study it thoroughly. Estimate the selling price of each horse

listed, mark it on the catalog page, and then compare it to the actual selling

price. Good buyers don’t miss by

much. Making a good buy is as important,

maybe more so, than making a good sale.

Studying the catalog carefully will

facilitate your inspection of the horses which interest you. In most cases, the horses will be on the sale

grounds a day or two in advance. In any

case, you’ll have a chance to see the horses hours before they go into the

auction ring.

You should have each horse that

appeals to you brought from his stall, walked away from you and back to you,

turned and trotted. Determine for

yourself if the horse is lame or travels sound.

Ask the handler all the questions you have concerning the horse’s

health, training, disposition, and his behavior since arriving at the sale. Don’t believe much of what you are told, but

ask! It is too late for questions after

the hammer falls. It is also surprising

how much you can learn from the idle chatter; listen carefully.

And give careful consideration to

what you are not told. Most handlers

will have a difficult time lying to you, but remember,

they are usually quite good at not telling the complete story.

If it is a performance horse sale,

make sure you attend the demonstration session.

An auctioneer will often let a horse

sell well below its true value, but smart buyers—and there will be plenty—will

seldom let a horse sell way above its potential for profit.

Buying correctly at sales requires

experience.

You have to be attentive. Many items on the catalog page may have been

corrected, added to or deleted. It is

your responsibility to get the “updates.”

You should know when to start bidding

on the horse you want and when to stop.

Don’t be the first to bid; let other establish the early lower

offers. And stop bidding when the

bidding reaches your estimated/acceptable price. You can’t pay the full price of the horse’s

potential as you see it, or there won’t be room for your profit margin. You should study how some buyers “shut out”

another bidder, and you should learn to catch sellers “running up”

bidders. Consignors often bid on their

own horses and quite frequently buy them back.

Don’t overpay by being caught in the excitement trap, or by allowing

your desire to get started now overshadow your business sense.

Many sales will have a medication

list. This reports all medications given

to any horse in the sale. Be sure you

check the list to see if horses you are interested in have been given

medication. If the sale does not have

such a list, check the “conditions of sale” in the front of the catalog to see

what rights you have in case you discover a horse you have purchased has been

given a medication.

Attend some sales just for practice

before you actually start buying and selling.

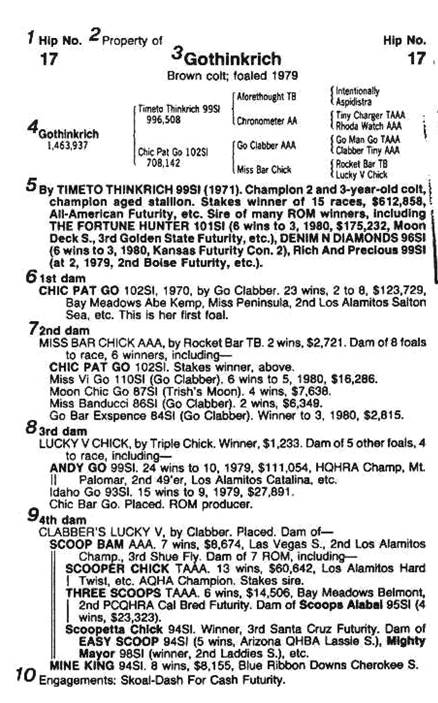

The sample catalog page which follows

is typical of the form used in major sales.

Catalogs prepared in the manner shown instantly give you an idea of the

quality of the horse offered. Some

catalog pages are much more difficult to read due to their organization.

Naturally, the wording in the sale

catalog is contrived to present the best picture of the horse’s pedigree and

performance record. Understanding what

is not mentioned in the catalog, and learning to read between the lines will

result in an even greater competitive edge than simply reading what is shown.

You absolutely must understand what

the omissions mean.

The catalog normally starts with a

title page offering the date and place of the sale. Several pages follow which list the

conditions of the sale, officials, a map of the sale location and barns, a

credit application, an agent authorization form, consignors, sires, dams,

reference sires, applicable state laws, and other pertinent information

particular to that sale.

Horses to be sold are listed one to a

page. To insure fairness in positioning

a horse in the catalog, most sales maintain a certain order, changing each year

or each sale. Fasig-Tipton,

one of the nation’s largest sales companies, lists the horses alphabetically by

the dam’s name, each year starting with a different letter of the alphabet.

The sample catalog page lists a Timeto Thinkrich yearling.

(1) The Hip No. refers to the horse’s

position of selling. Number 17 means

that this horse

was to sell

in the 17th position. But don’t count on

it. If you go out for coffee while the

14th hip is selling,

you may find you’ve missed Hip 17 because Hip 15 and Hip 16 were

scratched

or “outs” (taken out of the sale).

(2) The owner, consignor, or agent.

(3) The name of the horse, if named, and the

color, sex, and birth date. If a name

has

been asked

for, but not yet approved, the statement, “Applied For” will appear instead

of the name. When a name has not been applied for, the

color and sex will be

moved up

above the birth date and the horse will be identified as “Brown Colt.”

(4) The name of the colt repeated along with

the registry number, and the pedigree of the

horse

always listed on top, the dam beneath.

The registry number of the sire and dam

will also

be listed, unless one is a Thoroughbred, in which case “TB” will be

stated. The

American Quarter Horse Association

has a complicated system of registration.

Sometimes an owner neglects to apply

for registration, which may cause complications

when buying

from a private party. But in a sale you

can be sure the horse would not

have been

accepted if the registration was not in order.

In the case of unnamed foals,

or older

“appendix” horses, no registration number will appear.

If an asterisk appears in the

pedigree, it means the horse was foreign bred.

Along with the registration system

goes a grading system. Most breed

associations award points or titles to competitive horses. For Quarter Horses there may be some

combination of “A’s”, or awards, such as Register of Merit (ROM), or speed

index (S.I.). Such designations will

immediately follow the names of horses earning ratings or special awards.

In discussions of pedigrees, there

are certain rules which must be followed.

A foal is always “by” a sire, and “out of” a mare, never the reverse. Dams, granddams,

great-granddams, always refer to mares in direct

descent through the female. They always

appear on the bottom line of each generation, thus sometimes referred to as the

“bottom line”, or more correctly, the “tail-female”.

The top line of each generation, on

the mother’s side, is referred to as the “tail-male”.

Numerical ordering is reserved

for successive female sides, the tail-females.

Thus the “first dam” is the horse’s mother. The “second dam” is the grandmother (the

dam’s mother), and the “third dam” is the great-grandmother (the second dam’s

mother).

While the sire’s mother is also the

horse’s grandmother, she is never called that; instead, she is the “sire’s

dam”.

It is common to hear a horseman say,

“This colt is by Timeto Thinkrich,

out of Chic Pat Go, by Go Clabber.” Thus

your attention is always drawn to the female side of the pedigree. Seldom does a novice investigate the dam of

the sire of a prospective purchase. Such

investigation should always be made as it can be extremely revealing as to

potential, that all-important concept for making money.

(5) A brief summary of the sire’s racing

accomplishments, his foaling date, and his

performance

at stud. Note that this summary is in

bold face type. A great deal more

information

is desirable and available about the sire than can be contained in one

paragraph,

but you will have to research it yourself, and you should.

You should be well enough versed in your chosen field to know which

sires produce high-priced offspring and which do not. You should know the stud fee of the sire,

and have a good idea of the annual average selling price of his yearling colts

and fillies. You should be aware of

colts and fillies. You should be aware

of performance ability and the disposition of the sire’s offspring.

Remember, the sire, if older, may

have sired many good foals, but with limited space, it is nearly impossible to

give more than a short report on his performance at stud.

The mare most likely will not have a

produce record of more than 10 foals, so her entire record can be reported.

You will constantly hear the

expression “black type”. It is an

extremely important part of buying potential.

There are two rules. A stakes

winner’s name will be capitalized in bold face (very black) type. A stakes placed horse’s name will be in bold

face type, but not capitals. If you are

purchasing horses other than race bred horses, the produce record of the bottom

line remains just as important. Mares

which produce outstanding performers in any field have great profit potential,

and so do their offspring. The foals, if

good, will have awards and accomplishments as important as black type.

Non-racehorse

sales will also provide catalogs and the "black type system" will be

used. In the front of the catalog will

be an explanation of the system. An

example of the system used by the Ohio Quarter Horse Association's Congress

Super Sale is:

BOLD CAPITAL LETTERS

- World Champions, AQHA and APHA Champions, Superiors, National Cutting Horse

Association Bronze, Silver, Gold & Platinum awards, and or money earners of

more than $10,000.

Bold Upper/Lower Letters

- Reserve World Champions, PHBA, IBHA and ABRA World Champions, ROM earners,

NCHA & NRHA Certificates of Ability and/or money-earners of more than

$1,500.

All

other performers appear in regular type.

Even though the sire’s paragraph

record is short, much can be deduced.

The principle of listing the best first is followed. The line “stakes winner of 15 races,

$615,858, All American Futurity,” etc. tells much more than it says. You can conclude he won more than one stakes

race, but only one of major importance, or it would also have been listed. At the time of this sale, The Fortune Hunter

was his best foal, and his victory in the Moon Deck Stakes and his third place

finish in the Golden State Futurity carried more importance than did the Kansas

Futurity Consolation placing of Denim N Diamonds. (Of course, Denim N Diamonds later became a

World Champion and a much more important offspring to Timeto

Thinkrich. The

future held more profit potential for Gothinkrich.)

(6) The first dam starts the summary of the

“tail-female” or “bottom line”, giving the

birth date so

you will know the mare’s age. The dam’s

name will be listed in

capitals,

but in light face type unless she is a stakes winner or stakes placed.

If the latter then it will be lower

case letters, but bold face, or “black type”.

In

this case,

the first dam is a stakes winner, so her name is listed in both capitals

and bold

face. Her sire’s name is listed, then

the number of races she won, the

number of

years she raced, that is from two-years-old to eight-years-old,

and the

amount of money she won. You can tell

she won only two stakes, because

two are

listed, then a second place finish in a stakes is reported. If she had won

more than two

stakes, all would have been listed. The

second place finish would

have been

dropped if space for stakes wins was needed.

The catalog then states the horse

being offered for sale is this mare’s first foal. This is important, for not only must all

foals be accounted for, but you must also account for all foal-bearing

years. If a mare has many barren years,

you want to know why. In this case we

know she raced until she was eight (1978), so the mathematics work out. This is the

first possible year that under normal circumstances, she could have a yearling.

A word about the

race comment following the mare’s name.

If she raced, the record will be given.

If she was unraced, it will say so.

Only if the mare raced and was unplaced will no comment be made. This is virtually true of non-racing horses

also. If a mare has performed even

fairly well, the catalog will list even minor awards. If the mare has not distinguished herself in

any field, there will be no comment. Another

case of the un-said providing needed decision-making information.

The catalog shows Chic Pat Go has

lots of potential.

(7) The second dam offers the highlights of

the female family, but not all the details.

Miss Bar Chick, as you can see

immediately, has not won or placed in a stakes

event

because her name is in light face type.

Money won is also important, but no

matter how much she won—it could be in the hundreds of thousands—she could not

earn “black type”. In this case, she had

two wins, but only earned $2,721. This

tells you her races were not quality races, the purses being under $3,000. Purse distribution varies at each race track,

but the winner normally gets about 55 per cent of the purse. Miss Bar Chick was not running for much

money, and her races were won at weak racing locations. You do know she earned a Triple A rating, and this is a minor plus in terms of her

value. With non-racing horses, you must

know what events are considered high quality and what awards create potential

for prospective purchase.

The next comment is tricky. “Dam

of eight foals to race, six winners…”

The catalog does not tell you how many foals she had, or why they didn’t

get to the races. But it does tell you

she had more than eight foals, and that for sure she had two which did race,

but couldn’t win. Furthermore, as only

five foals are listed, the sixth one to race definitely wasn’t much.

You should also know the value potential of stakes races or the

importance of other competition.

A weak stakes win or a victory at a very small show doesn’t carry much

value potential. Any other

accomplishment which does have dollar value will be listed, even if the event

is relatively small.

(8) The third dam, Lucky V. Chick, is reported to have produced five

other foals, four to

race. The five other foals reported do not include Gothinkrich’s second dam, Miss Bar

Chick.

The catalog only lists three of Lucky V Chick’s foals. Of course, some omissions are necessary due

to limited space, but in this case, Chic Bar Go never won, yet is still

listed. Consequently, you can be sure

the unlisted foal was worse than Chic Bar Go.

Sometimes after a mare’s name

and record, the statement “producer” will be made. This means the mare had produced at least one

winner. It always means just that, no

more, no less.

(9) Fourth dam. If a catalog includes the fourth and fifth

dams, then it is an indication the

previous

dams were not outstanding. Or it may

mean the fourth and fifth dams were

exceptional,

as in this sample. Then too, the fourth

and fifth dams are older and have

time to

produce good foals. Here, the first dam

has had only one foal, so extra space is

available

for the fourth dam, which has produced lots of black type.

You must weigh all the factors in

deciding why a fourth or fifth dam has been included. Personally, I prefer so much black type or

listing of awards and achievements in the first three dams that there is no

room for the fourth dam. What is “up

close,” meaning the “immediate family”, is what has profit potential.

(10) Here the catalog entries will change

according to whether the horse to be sold is a mare,

a horse, a

weanling or a yearling.

A yearling, and in some cases a

weanling, will have “engagements” listed, telling you to which important races

or shows (futurities) the nomination fees have been paid. Engagements are usually indicators of profit

potential.

A broodmare will have a race record,

a produce record, and if she has a foal by her side, the foal’s birth date and

sire’s name. Finally, if the mare has

been bred, a pregnancy status is reported.

The words, “believed to be in foal” are no guarantee the mare is in

foal. If you are buying potential for

profit, have the mare pregnancy tested prior to purchase at your own

expense. The breeding date and the sire to

which the mare has been bred should be listed.

If the mare was not bred, the catalog

should state, “not bred,” or “open.”

In the case of two-year-olds or

older, the training status or race status should be given, such as “unraced”,

“placed twice in four starts”, “galloped 45 days”. Comments for horses not intended for racing

might include “halter prospect”, “finished in top 10 at first show”, “loads

well”, or “prospective jumper”.

With horses, there is a special

terminology applied to relatives.

Because a sire can have so many

offspring, while a mare has only one foal a year, horses are never referred to

as half-brothers or half-sisters unless they are out of the same mare, but by

different sires.

If the horses are by the same sire

and out of the same mare, then they are full brothers, brother and sister, or

full sisters.

A foal by the same sire, but out of a

different mare, is never a half brother or sister, but is called a foal “by the

same sire.”

A final comment about the catalog

page you construct or are given. Black

type, awards, and permanent record achievements never become less than shown,

but can constantly be added to by members of the family.

Hip No. 17 is by a young sire, out of

a young mare. (Always potential, as

nothing bad has been proven.) Both have

the potential to add more and better black type or awards to their records. (The sire certainly did.) This may make Gothinkrich

more valuable to some extent at a later date if he remains a colt. (More sales sizzle.) And similarly, his good performance will

positively increase his dam’s value and the value of her subsequent foals.

Assignment:

1.

Construct a catalog page for this horse:

My

Kustom Kruzer: 2011 dun

Quarter Horse gelding, AQHA #5354357, ABRA #P-20261 (double registered), AQHA

Incentive Fund, NSBA Breeders Championship Futurity eligible

His

pedigree can be found at:

http://www.allbreedpedigree.com/my+kustom+kruzer

2. For what does this horse have potential based

on your research? (He is not bred for racing,

so do not apply racing terms to your report - determine his potential based on

his pedigree.)

Submit

your report to Eleanor Blazer elblazer@horsecoursesonline.com

(attach the catalog page to the email)

You

can fax it to