The Business of Making Money with Horses

By

Don Blazer, taught by Eleanor Blazer

Lesson

Three

Weanlings: Big Potential for Profits

At first glance, selecting a weanling

of any breed seems to be the biggest gamble of all.

It is not! In fact, it may be your safest return on

investment opportunity.

On the surface, you are dealing with

a baby from three to 11 months old, unbroken except to lead and groom, and

essentially untrained. And it is

difficult to know exactly what you will have in a year or more. All this tends to make a lot of people stay

away from weanlings, which means their price, at sales, is usually less than

their true value. (Consider the fact

that most weanlings sold at public auction will bring only about the cost of

the breeding fee. Someone other than you

paid to have the mare bred, paid to keep her for the gestation period of 11

months and 10 days, and paid to keep both the mare and the foal until sale

time. Add to all that expense the normal

health care costs, and it is easy to see a healthy weanling at the price of a

breeding fee is a steal.

So immediately you know you have two

factors to your advantage. First, no

matter what weanling you purchase, you know that in most cases you won’t overpay

if the price is about the same as the stallion’s service fee. Second, most of the buyers at a sale are not

interested in weanlings, so it is easier for you to acquire your top selection.

There are a lot of risks between the

date of breeding and the time a horse begins to perform, whether it is racing,

cutting, jumping, or driving. With the

purchase of a weanling, you are splitting the cost of taking a horse to the

point of performance. The price you pay

for the weanling is the reward the seller gets for assuming the risks from

breeding to weaning. If the seller

doesn’t make a profit, that’s his problem.

He probably didn’t know how to have horses make money for him. If you buy a bargain, for you it is another

step to a big percentage return on a small initial investment.

When you sell your purchase, you will

get the reward for assuming the risks from weaning to point of sale. And those risks can be minor since the horse

is generally under no major stress.

At the time of reselling—with no

effort on your part—you have two more factors which are working to your

advantage.

First, yearlings and horses ready to

perform almost always bring the highest sale prices. (The exceptions are the elite stallions and

mares just ready to begin breeding, and stallion or mare syndications.) Secondly, the high rollers are willing to pay

an extra bonus for yearlings and horses ready to perform because they are eager

to get started; they want action now, and they want your horse!

If you buy a healthy, sound weanling

at a sale, and you care for it until it is a yearling, or is ready to perform,

you will undoubtedly make a profit of some sort if you sell prior to the time

the horse enters any form of competition.

You may have to tell someone you have

the horse for sale, but sometimes, even that isn’t necessary. I have purchased weanlings and resold them at

a profit in less than three hours. (It

has happened more than once when other buyers realized what a bargain I had

purchased. I took a small profit—large

percentage—and they still got what they wanted at a very reasonable

price.) Weanlings are very salable.

However, you are in the business of

having horses make you a lot of money, so you won’t purchase a weanling just on

surface appeal. You will be doing a

great deal of studying. That means you

will read every page of the sale catalog and you will compare every weanling

offered with every other weanling. You

will be looking for potential. (If you

are looking for potential in weanlings not at a public auction, then you will

have to construct your own catalog page.

Develop the catalog page well in advance of looking at the

weanlings. You can develop your catalog

page by getting the name of the sire and the dam from the seller, then

contacting the breed association for pedigree information.)

The purchase of a weanling, as the

purchase of any other horse intended to make a profit, is based on potential

and no other factors.

To reduce the risks of a weanling

purchase even further, most horsemen, including myself, recommend buying

fillies. If a colt can’t run, win at the

big shows, cut cattle, or jump, then both your resale and

stud service potential are gone.

Not just reduced, but gone!

You might get lucky and sell the colt

(probably now a gelding) for a private pleasure horse, but you can be sure you

won’t get much. Your possible resale

buyers know the risks inherent with a colt, and so they are not anxious to

spend the big bucks on anything less than a stallion prospect with superior

bloodlines. Even a great-looking colt

without an impeccable pedigree is a risk the majority of buyers at sales don’t

want to take. On the other hand, if a

filly can’t run, jump, or win the big shows, she can almost always produce

foals. (You don’t want her as a

broodmare, because she most likely won’t make you a lot of money, but that’s

covered in another lesson.) But because

she can produce foals, someone will buy her.

Older mares without a record still average a better resale price at

sales than do older geldings or stallions without a record.

That’s taking a negative look at

some good reasons for buying a filly.

But looking at the positive side, the picture is much brighter. Fillies generally bring higher prices at time

of resale. Colts with

weak pedigrees, whether weanlings, yearlings, or two-year-olds, do not command

good prices. A colt with an

average pedigree will bring less than a filly with an average pedigree. Fillies and mares maintain a higher average

sale price at public sales than do stallions and geldings. (At “performance sales—the best performers,

regardless of gender, bring the biggest prices.

They are the ones with “potential.”)

The only time colts demand more than fillies is

when the colts are extremely well-bred, good-looking and have big potential as

a performer; then they are most often the sale toppers.

Of course, there is always the

private sale, when almost anything can happen, and usually does. There is no ceiling on the price of fillies

or colts at private sales. Colts do just as well as fillies at private sale, as you will note

in an upcoming example.

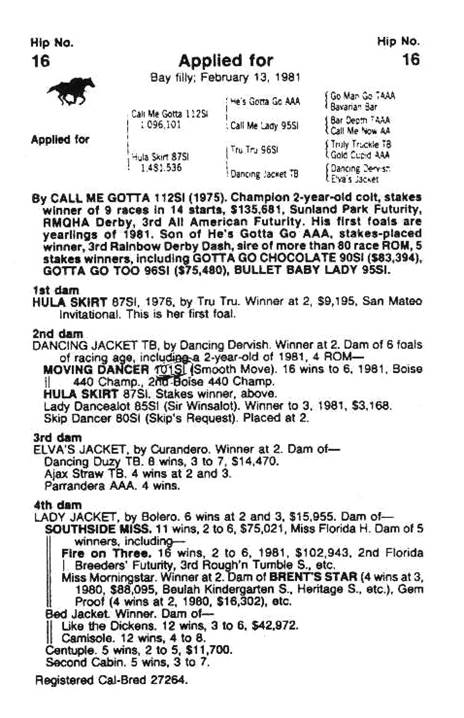

The first example is an unnamed bay

filly by the stallion, Call Me Gotta.

This filly, foaled on

Call Me Gotta

was a good race horse with solid bloodlines.

As the catalog sheet shows, he was a Champion two-year-old, stakes

winner and earner of $135,000. At the

date of the sale, his first foals are yearlings, so there are no facts about his

ability to produce, just POTENTIAL.

The first dam is Hula Skirt, a stakes

winning daughter of Tru Tru. Hula Skirt only had an 87 Speed Index, and it

would be best if you could purchase the offspring of a Triple A (

The weanling filly offered is the

first foal of Hula Skirt, so she has no proven produce record, only POTENTIAL.

The second dam, Dancing Jacket, is a

Thoroughbred, without a speed index. She

was a winner, but not of much. This will

keep the price of the weanling down slightly.

What will increase the weanling’s price, and her later resale price, is

the fact that Dancing Jacket produced two stakes winners out of six foals. Four of the six foals earned the Register of

Merit (ROM) and one of the six was too young at the time of the sale to have an

established record; more potential.

The third dam did not do much,

but the fourth dam was a winner and produced a stakes winner,

and a stakes-placed mare Fire on Three, who ran out more than $100,000.

Note how well the female side of this

breeding has done. The weanling

considered is a filly. There is enough

black type in the pedigree to guarantee more sizzle for the potential of the

weanling being offered.

This is the kind of pedigree you

seek; it is full of potential. It

doesn’t matter what breed you are purchasing.

It is all the same—Paints, Arabians, or National Show Horses—everyone is

seeking a satisfaction and the horse you are looking for must have the

potential to provide it. If the catalog

sheet shows a lot of winners, at any event, then you’ve got potential for big

profit in purchasing and reselling any weanling which interests you.

You are hunting for the catalog sheet

which offers great potential. You are

not looking at horses; you are looking at the potential they offer. You’ll look at the horse later.

If the weanling is the daughter of a

stakes winner who has produced stakes winners, the price of the weanling will

probably be too high to make her a good purchase. Too much of a good thing will make it more

difficult to produce a big return on investment without adding a positive

performance record. And adding a positive

performance record can be very difficult.

Once you go into competition, if the filly doesn’t perform exceptionally

well, then she will be a bigger profit loser.

This is the case of a modestly-priced weanling being a better deal.

If the catalog sheets show no black

type, no winners, no horses of merit, then even if the weanling goes for

nothing, there is no potential for profit at a later sale. Skip very cheap horses. They are cheap because they have no potential

and there is no way short of a miracle for them to attain the needed potential.

Hip No. 16 at the McGhan Sale sold for the amazingly low price of $8,000.

The filly was subsequently entered in

the All American Select Yearling Sale at

The performance chart on the filly

shows a number of costs involved with her maintenance and subsequent

resale. The cost of the weanling is a

fact.

In any case, even with the high

estimated costs, the filly produced a profit of $16,540 in less than one year.

She produced a return on investment

of 122.8 per cent.

Unnamed

filly by CALL ME GOTTA—Hip No. 16

|

|

Expense |

Income |

|

Cost of weanling |

$8,000 |

|

|

|

$480.00 |

|

|

Veterinarian |

$380.00 |

|

|

Farrier |

$100.00 |

|

|

Pasture, 10 mos. @

$100 per mo. |

$1,000 |

|

|

Additional hay |

$200.00 |

|

|

Grain and vitamins |

$200.00 |

|

|

Transportation to

sale |

$300.00 |

|

|

Preparation at sale |

$300.00 |

|

|

Futurity payment |

$500.00 |

|

|

Cost of entering

sale |

$500.00 |

|

|

Selling price

received |

|

$30,000.00 |

|

Sales commission |

$1,500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total cost and

expense |

$13,460 |

|

|

Total income |

|

$30,000.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Net

Profit……..$16,540 |

|

|

Return on Investment

(ROI) 122.8 per cent.

(Total amount of profit divided by

total investment.)

Now, if 122.8 per cent return on your

investment in less than one year isn’t a lot of money, I don’t know what is.

Considering the initial dollar outlay

was only $8,480, and the other expenses averaged only $440 per month, you have

a small investment. But if you took the

same total a mount of money--$13,460—and put it in a treasury bill at the

all-time high of 16 per cent, you would only have earned a profit of

$2,153. A 16 per cent return on your

investment would be considered an absolutely phenomenal return today, but it

certainly won’t make you as much money as a 122 per cent return. And if you put the money in a savings account

at 2.5 per cent yield, the only absolute is that you will lose money. Inflation in 2002 was low at only 3 per

cent. In a savings account there is no

risk…..you would have positively lost one-half per cent on your money in

2002. What interest rate are you getting

today on your savings?

Also, keep in mind that you really

didn’t have a cash outlay of $1,500 of the $13,460 in costs. The $1,500 was a sales commission which was

paid after the sale and prior to the time the $16,540 in profit was paid.

If you take off the $1,500, which did

not come out of the seller’s pocket, then the total out-of-pocket expense was

only $11,960, making the monthly cost of maintenance an out-of-pocket expense

of only $340 per month.

A ROI of 122.8 per cent on an $11,960

investment in less than one year sounds almost criminal. But it is a fact, and it happens, and it is

easy to do again and again and again.

If $16,000 in profits is not big

enough for you, then you’ll want to go into business on a little larger

scale. Words of caution—don’t invest

your lunch money. Know what you can

afford to lose.

You can play the Make Money With Horses game on any level you like. It is up to you.

Here’s what you can hope to do if you

play with more dollars. These examples

don’t happen every day, but fortunately for us, they happen often enough not to

be considered uncommon.

Majorie Cutlich purchased a weanling for $15,000. We don’t know for sure what she spent in the

next eight months to care for the weanling, but let’s say she spent

$10,000. That makes her investment

$25,000. She sold the weanling after

eight months for $270,000, giving her a profit of $245,000.

That kind of profit and return on investment

ought to satisfy anyone.

But how about Donna

Wormser who bought a weanling for $14,000? Let’s say she also spent $10,000 keeping her

horse for 10 months. She resold her

$24,000 investment for $375,000 to make a net profit of $351,000 in less than

one year.

If you think you can’t make money—big

money—in the horse business, think again.

Pinhooking is such big business now,

that the major breed magazines include the activities of pinhookers as part of

their report on horse sales.

When buyers are optimistic about the

potential a horse offers, expect to see pinhookers making unbelievable

returns. The last time I looked,

pinhookers in the Thoroughbred industry were enjoying a very nice rate of

return of 88.4 per cent. That was up

from 56.8 per cent the year before. This

is the age of opportunity for making money with horses.

Recent reports show weanlings costing

less than $10,000 at the major Thoroughbred sales have resold for an average

price of $40,000; that’s a 148 per cent return on investment. Weanlings selling between $10 and $20,000

were returning 118.6 per cent. Now just

so you will realize it is not all roses, weanling selling for between $30 and

$40,000 returned only 16.9 per cent that year.

Here’s another great return, except

it is calculated on a very small budget.

This example is a colt. I don’t recommend buying weanling colts for

resale at sales, but they do make money.

This colt was not resold at a sale, but was sold privately.

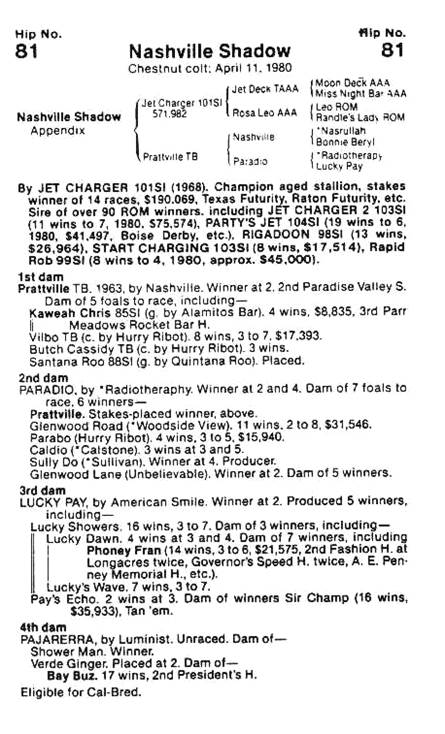

Nashville Shadow was purchased at a

sale. His pedigree did not have as much

potential as I would normally like, but it had some. The colt was an outstanding individual conformationally, which added substantially to his

potential.

The first dam was a stakes-placed

mare that had produced five foals to race.

Three were winners, one of which was stakes placed. The mare, however, was an older mare—17 years

old. She obviously hadn’t produced as

much as we would have liked, and it wasn’t likely she would produce more.

What made me buy this weanling was

the fact the mare had a very good-looking yearling colt which sold prior to the

full brother weanling. When the yearling

brought an excellent price, the weanling suddenly had a lot more POTENTIAL!

|

|

Expense |

Income |

|

Cost of weanling |

$1,300.00 |

|

|

|

$78.00

|

|

|

Veterinarian |

$300.00 |

|

|

Farrier |

$100.00 |

|

|

Board, 7 mos. @

$135 per mo. |

$945.00 |

|

|

All American

nomination fee |

$50.00 |

|

|

Total cost and

expense |

$2,773.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sold privately |

|

$6,500.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Net

Profit……..$3,727 |

|

|

Return on Investment (ROI) is 134 per

cent.

Jet charger had proven himself to be only a fair sire. He produced runners, but his potential—at 12

years of age—was limited.

Nashville Shadow was worth a risk

only because he was a good-looking colt, his selling price was low--$1,300, the

catalog sheet shows some black type and possibilities, and he had a yearling

brother ready to go into race training, which could add some new sizzle to the

potential. Still, this type of purchase

should not be a high priority. It was a

legitimate purchase by the rules, but not a great buy. The example is included only to demonstrate

that weanlings frequently offer big rewards on small investments.

Nashville Shadow was entered in the

All American Futurity, a million dollar race, to provide some sales

appeal. The initial cost of entry was

only $50, so the investment was minor in comparison to the “sizzle.”

The colt was not advertised, but was

shown to normal barn traffic. One such

person liked the colt and purchased him for $6,500. The profit on the colt was $3,737 and the

return on the investment was 134 per cent.

Not bad for a horse held only seven months. Not bad, and yes, lucky. But you make your own luck.

When you consider the total

investment was only $2,773, the profit was considerable.

The final example is included to show what

happens when the rules are not followed.

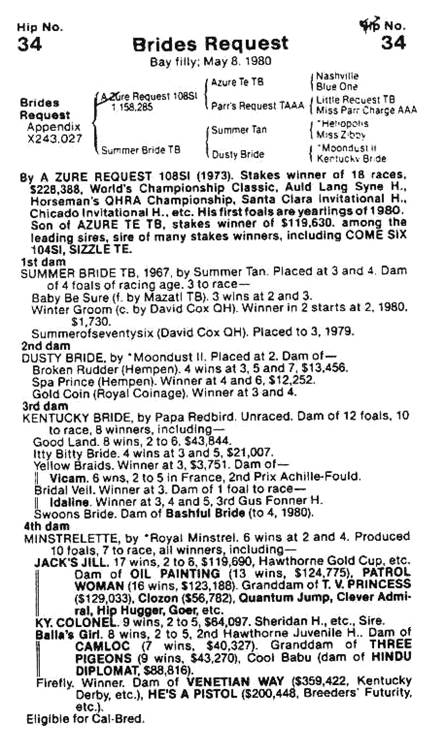

Brides Request is a filly by a young

stallion, A Zure Request. As shown by the catalog sheet, A Zure Request did very well as a race horse, and has the pedigree

to be a good sire—that’s potential, and it’s what you’re seeking.

The first dam, however, puts the

purchaser of this filly in trouble. A

Thoroughbred, Summer Bride was not a winner.

She only placed at 3 and 4, which proves she wasn’t a good race

horse. There is no potential there.

As a producer, Summer Bride is the

dam of four foals, three of which went to the races. Two foals were winners, and one of the two

was a Quarter Horse, the same as Brides Request. That shows an ounce of potential. But even a pound of cure won’t make up for

the lack of “sizzle” come sale time.

The second dam, Dusty Bride, was not

a winner, although she produced three winners.

But do three winners add up to potential? In this case, no. None did much. And earnings of $13,456 for a Thoroughbred

are very small.

The third dam shows no potential

either. And by the time you get to the

fourth dam, even the black type there is too little, too late.

Brides Request sold for $2,000 as a

weanling, and the cost of keeping her until sale time as a yearling were

minimal. The total cost and expense was

$5,495.

The selling price at the All American

Sale was $6,500, and was predicated on the potential of the stallion, A Zure Request. (A Zure Request later proved himself the sire of some speed,

and gained modest popularity.)

The net profit on the weanling filly

was $1,005, and the ROI was 19 per cent.

Granted 19 per cent return on an

investment of only $5,000 is pretty good in comparison with many other types of

businesses. But it was somewhat risky

because the total potential was weak. The potential of the stallion and the fact that the weanling was a

filly—two of the rules to follow—are the only two things which saved this

investment. Pass when the

weanling offered doesn’t show excellent potential on the catalog sheet.

BRIDES

REQUEST

|

|

Expense |

Income |

|

Cost of weanling |

$2,000 |

|

|

|

$120.00 |

|

|

Veterinarian |

$300.00 |

|

|

Farrier |

$100.00 |

|

|

Board, 10 mos. @

$135 per mo. |

$1,350 |

|

|

Transportation to

sale |

$300.00 |

|

|

(Owner

groomed and showed |

|

|

|

horse

- no outside costs) |

|

|

|

All American

Futurity payment |

$500.00 |

|

|

Cost of entering

sale |

$500.00 |

|

|

Selling price

received |

|

$

6,500.00 |

|

Sales commission |

$325.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total cost and

expense |

$5,495. |

|

|

Total income |

|

$

6,500.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Net

Profit……..$1,005 |

|

|

Return on investment (ROI) 19 per

cent.

Weanlings are good profit makers, and

often require a small investment and very little physical work. But you must follow the rules.

Rules for Pinhooking

1. Purchase fillies.

2. The weanling must be by a well-bred stallion who has proven himself a better

than average

performer, but does not yet have a long record as a sire.

3. The first dam must have proven herself an

excellent performer, or an excellent

producer. The produce of an average first dam should be

passed.

4. The second dam must also be a performance

winner, or the producer of

performance

winners. The second dam is still very

important when seeking

potential. She must show it. If the second dam is stronger than the first

dam,

that is even

better. But a strong dam can never make

up for a weak first dam.

Do not fall in to the trap of thinking you

can slip one through and make a big

profit based on a

strong second dam. Smart buyers just

won’t pay the price, and

the less than

bright buyers only purchase cheap horses.

5. The third and fourth dams are not too

important. A lack of black type or

performance

record will not hurt. Third and fourth

dams, however, should have

produced

something. If they haven’t produced,

then the entire line lacks potential.

6. The weanling must be sound and without

obvious injury when purchased, and when

resold.

Potential is the key! The weanling being resold as a yearling will

make money if she is good-looking, is by a solid, yet unproven sire, and is out

of good-performing and/or producing first and second dams.

If you don’t follow these rules,

don’t blame anyone buy yourself if the weanling doesn’t make money.

And if you say it’s too hard to find

weanlings which meet all the requirements, you are wrong. It’s not too hard, it’s just hard. That’s one of the reasons buyers aren’t

making a log of money with weanlings.

Pass the ones which don’t measure up

in conformation, blood, and potential.

It is always better to pass 500 than to buy one bad one. If horses are going to make you a lot of

money, then you’ll have to put in a little effort and a lot of patience.

Don’t buy because you are caught up

in the excitement of the sale. Don’t buy

because you want some action. And don’t

buy hoping your normal good luck will make things turn out well.

If the dollar amounts in the examples

are not big enough to suit you, just play with bigger bucks. (All breeds have the same potential for

enormous returns on small investments.)

You can play at any financial level.

And you can play with more than one horse, so you can double, triple or

quadruple your income anytime you choose.

The scale on which you decide to get

started is completely up to you. The

important thing is to get started. It is

a business, and time is money, and you could be making a lot of it, now!

ASSIGNMENT:

Refer to this

page:

http://www.horsecoursesonline.com/college/money/lesson_3_catalog_pages.pdf

This page

shows the catalog sheets for three 2012 yearlings by the same stallion - Zippos

Mr Good Bar.

They are out of different mares and were all sold at the 2013 AQHA World

Show Sale in the fall of 2013.

Your

assignment is to review the catalog pages and determine, as weanlings, which

one had the most potential to make money when they sold as yearlings. Please list them in order of potential and

tell me why you listed them in that order.

Send your

report to elblazer@horsecoursesonline.com. Be sure to include your full name and email

address on the document.