REALLY, REALLY SIMPLE ACCOUNTING

By J. M.

Blazer

As a stable manager, you may be asked to do the

bookkeeping…the following is a simple bookkeeping system for your use. There is no quiz with this lesson…you will be

tested often enough as you learn all the steps of bookkeeping.

More

than 18 million people are running their own businesses. Millions more are considering it. In 2005, these sole proprietorships accounted

for $969 billion in revenue. If you are

starting your own business, you are going to add to those numbers.

All

of these entrepreneurs need to keep records.

Why? Because

the Internal Revenue service says so.

“Your records must be permanent, accurate, complete, and must clearly establish

your income, deductions, credits, and employee information”.

The

law requires records, but the law doesn’t require you to keep your records in

any particular way. Nor does it tell you

how to run your business.

Of

course you want to know how your business is doing. So for your own enlightenment, you must have

some understanding of the bookkeeping.

This booklet will help you with that, but it is NOT going to even attempt

to make you a bookkeeper or accountant.

In

fact they would be very foolish if they did.

This booklet tells you what you need to know, and nothing more, so you

can spend your time growling and improving your business, not doing

bookkeeping.

You’ve

heard of debits, credits, left, right, increase, decrease. And you know of profit and loss statements,

balance sheets, income statements, and statement of condition.

Forget

about them. All you need to know is

whether you had a profit or loss. This

system will show you that, as often as you want.

BANKING

Bookkeeping

is only the recording phase of accounting.

It accumulates the data needed to prepare financial reports. Good records are needed for good

management. You will need to know what

your receipts and expenses actually are.

In some cases, it could be important to know the type, or source of

revenue. You must decide if it is

worthwhile to provide certain categories and classifications.

Accounting

is analyzing, interpreting, summarizing, and reporting the information that has

been gathered. This helps in planning

and making decisions.

First,

you should have a separate bank account for all your business

transactions. It is not required, but it

is sure easier. It makes sense not to

mix your personal and business receipts and expenditures. If you make any money at all, you are going

to pay taxes on it. So don’t have a mess

at the end of the year trying to separate taxable income and deductible

expenses.

Don’t

pay by cash if it can be avoided, but if absolutely necessary,

be sure you get a paper receipt. Don’t

use a credit card, it fouls up your records because

the statement is always a month later than the transaction. But if you must, get a card for the business

only, and keep it that way---business purposes only!

Don’t

write checks to yourself or to “cash”.

Don’t write any checks until you have some type of bill, voucher, or

receipt to verify its business purposes.

If you don’t have one, and can’t get one, and still have to write the

check, then make your own voucher on a blank sheet of paper. Remember, to be deductible as a business

expense, an expenditure must be “ordinary and necessary, and directly connected

to your business”.

Copies

of invoices you send to customers and that have been paid by the customer, bank

deposit tickets showing the checks you have received, are all verification of

your receipts. The bills, invoices,

statements that you have paid, are verification of your expenses. These are called “documents of original

entry”, but you don’t have to remember that.

All

small businesses should be on a “cash basis”.

That means revenue is recorded when you actually receive the cash. So there is no need to “Accounts Receivable”

or “Bad Debts”. Charging off bad debts

is eliminated. You will have bad paying

customers, but they will never get into your books until they do pay.

ACCOUNTS

What

is an account? An account is a name we

give to a grouping of the same or similar transactions. For instance, payment of rent creates a “Rent

Account”. Your checkbook is your Cash

Account, and you should keep it up to date and balanced. But as we are only interested in revenue and

expense here, leading to the determination of profit or loss, we won’t be using

a cash account here.

By

naming the account, we know where to allocate, or assign, the similar items and

transactions. Besides depositing the

receipts, and paying the bills, you need to keep these documents some place in

an orderly fashion. Get file folders at

any stationery store and label them for the types of receipts and expenses that

you will have.

After

you have properly recorded the transaction, all the paperwork generated by that

transaction will go into the appropriate file folder. Thus your supporting

documents, or “backup” will be readily available when necessary.

You

may set up an account (that is, name it), then never use it. Obviously we don’t want that. Only when you think you are going to have a

lot of the same kind of transactions, start an account for them. But seldom occurring events can be combined

under one comprehensive title. For

receipts, “Sales” can cover everything.

Only if it is absolutely necessary to know, would you divide it into the

different type of sales.

For

expenses, the

If

you stick to the

RECORDING

Now

you need a place to list all the transactions affecting your newly named

accounts. You list them in chronological

order, total them at the end of your accounting period, and you will know

exactly how much you received and how much you spent. Your accounting period can be any length of

time you want---a day, a week, a month, a year. From now on, we’ll assume an accounting

period of a month, because that is the norm, and we’re keeping this

simple. At one page a month, twelve

pages equal the year. For the same

reason, avoid using a “fiscal year”; a calendar year is just fine, even if your

business is seasonal.

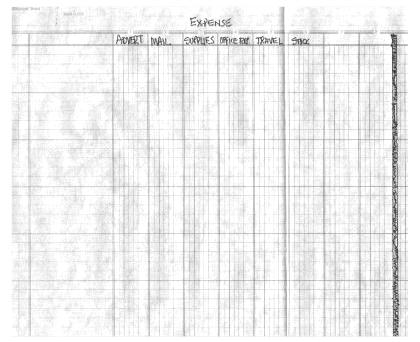

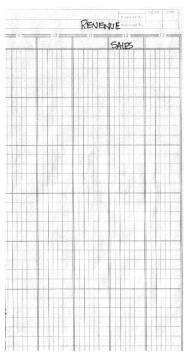

The

best thing for this listing is a columnar pad that you can obtain at any

stationery store. This is a pad

containing vertically and horizontally lined sheets. The horizontal lines are called rows, and the

vertical lines are called columns. Be

sure the pad you get has at the very least 32 rows, and at least

Put

a name or label at the top of each amount column, corresponding to the labeling

of your file folders. For instance,

column 12 could be “Sales”. If

absolutely necessary to separate categories of revenue, you could use two or

three columns. Draw a wide vertical line

between revenue and expense columns, to help avoid mixing them up. Now label as many expense columns as you need

for the different types of expense, according to your naming of accounts.

From

the bills, checks, and receipts you have obtained with each days transactions,

you enter the amounts in the proper column on that day’s row. According to the need and nature of your

business, you may need more than one row, but by combining the similar transactions

and entering totals, you can keep the use of rows to a

minimum. That’s why we want more than 30

rows for 30 days. Each row could contain

a single transaction or many transactions.

Explanation of entries can be used, but is not really necessary. Remember, if you have a question or need to

verify an entry or amount, go to the file folder for the original receipt or

bill.

At

the end of the month, total all columns.

Combine the revenue column totals, if more than one,

and this is your total revenue. Combine

the totals of the expense columns. The

revenue total, minus the expense total, is your gain, or profit. Or loss, if the expenses

came to more than the revenue. By

adding each sheet’s (or month’s) totals you obtain the revenue and expense

totals for the year, and these totals transfer right to the same named lines of

the

In

addition, all totals can be carried forward to the next months

sheet, combined with that month’s business for an accumulated accounting of how

you’re doing.

If

your business requires that you keep inventories of products you sell, then you

will need to know what the products you sold cost. Mainly because the

It’s

not as complicated as you might think.

Make a count of all the product you have on

hand. Calculate the cost of the total

amount of product, that will be your “Beginning

Inventory”.

On

your tabular sheets you will need to have separate columns for Purchases,

Labor, Materials and supplies. They will

be included along with all the other expense accounts in figuring your monthly

revenue, expense, and gain and loss.

But

at the end of the year, totals of these accounts will be separated for tax

purposes. On the back of Schedule C is

the format. On Line 35 is the beginning

inventory. Line 36 Purchases. Line 37, Labor, if you had any. Line 38, Materials. Line 39, we skip, because we don’t want to

explain what the “Other costs” were. If

you had any, they would fit in one of the other categories anyway. And these costs up on Line 40, calculate the

inventory at the end of the year, and subtract on Line 41, and you will have

your Cost of Goods Sold on Line 42.

Carry

that forward to the front of Schedule C, Part 1, Line

4. Subtracted from Gross Receipts, Line 1,

gives you the Gross Profit on Line 5, and if nothing is on Line 6, the Gross

Income on Line 7. All your other expense

columns are deducted in Part II to arrive at your Net Profit or Loss.

The

key here is correctly figuring the values of inventory. Assuming the beginning inventory is correct,

understatement of the inventory at the end of year will increase the cost of

goods sold, and thus incorrectly reduce your gross profit. Conversely, an overstatement of inventory

will reduce the cost of goods sold and thus falsely increase your gross

profit. Any error will be compounded

because the ending inventory of one year is carried over to the next year as

the beginning inventory, thus the profit or loss will be misstated for two

years.

Naturally,

the net profit will now be different from the profit or loss as figured on your

columnar pad, the difference being the result of any change in inventory

values, less the totals of the three columns that were used to calculate cost

of goods sold.

Click here for a link to

the

Click here for the

instructions on how to fill it out.

DEPRECIATION

Depreciation

is an annual deduction allowed to recover the cost of business property having

a useful life of more than one year.

Depreciation starts when the property is first placed in service. Recognizing that recovering the cost of property

is an incentive to investment, thus stimulating the economy, government has

become more and more lenient with depreciation.

There

are several different methods you are allowed to use. You calculate it yourself, using one of the

methods according to your needs.

“Straight Line” is merely dividing the cost by the number of years of

useful life. “Double Declining Balance”

allows a much larger amount to be taken the first year, smaller amounts in the

later years. But you can’t deduct a full

year’s depreciation if the property was placed in service after March, because

of Mid-Quarter and Mid-month conventions.

Get the instructions from

Rules

are much different for “Listed Property”.

Listed property is simply property this is not used 100% for

business. For instance, if you have a

truck you use in your business, but also go to the grocery store in it, you

technically have listed property, and that requires a whole lot of

figuring---mileage records, dates, times, percentages, etc. We don’t want that. So get another car, use that for personal

trips, and then you have a legitimate claim that the truck use is 100%

business.

Fortunately,

There

is also an income limit which limits the deduction to the taxable income of the

business, or the taxable income from all businesses combined, if more than one.

Two other restrictions, the property must have been purchased, and the

deduction can only be taken in the year of purchase.

In

your favor, you don’t have to deduct the full cost of the property. You can claim a portion of the cost and

depreciate the rest. This gives you a

break if the income limit applies, or if you already

have enough expense for this year and want to save some deduction for next

year.

You

won’t need a column for depreciation on your sheets. You will figure it out at the end of the

year. Then subtract it from the gain as

calculated on your sheets for the year.

Or add it to a loss. Then your

column sheet gain or loss will be the same as on Schedule C.

DEPRECIATION COMPUTATION

2001 Dodge

Pickup truck, Horse Trailer Hitch Installed

Placed in

service,

Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery

System (MACRS) Straight Line

Business investment use, 100% GDS recovery period,

five years.

Mid Quarter Convention applied

Cash Price $18,477.22

Less:

Trade in old truck 2,200.00

Balance to be depreciated $16,277.22

2001 Depreciation, per Pub.

946 table 2.5% $ 406.93

2002 Depreciation 20% 3,255.44

2003 Depreciation 20% 3,255.44

2004 Depreciation 20% 3,255.44

2005 Depreciation 20% 3,255.44

2006 Depreciation 17.5 2,848.51

Total Depreciation Allowable $ 16,277.20

Click here for a sample of

the 2006

Click here for instructions

on how to fill it out.

EMPLOYEES

To

be deductible, an employees’ pay must be an ordinary and necessary business

expense. In addition, it must be

reasonable, be for services actually performed, and incurred in the tax year.

You

cannot deduct your own salary or any personal withdrawals you make from the

business. You are NOT an employee of the

business.

If

you have employees you will have to report---and pay---employment taxes, which

include the following, Social Security, Medicare, Federal unemployment, and

State employment. Besides employer

taxes, you also have to obtain from each employee a W-4 form and withhold their

taxes from pay and, in turn, pay that to the Federal and State agencies. Reporting periods are monthly, quarterly, and

yearly.

To

do it properly, you should also have a third bank account just for payroll and

to accumulate payroll taxes. The amounts

you owe, and the amounts you withheld from the employees IS NOT YOUR MONEY! More businesses have failed and/or been

charged with crimes over mixing and using this money for their business

needs. For this bank account, get a

special checkbook with payroll stubs for you and the employee. And you’ll have to have a special payroll

journal, with sheets divided quarterly for each employee, and a summary sheet,

to record each payday, total quarterly, and again yearly, to furnish the state,

the

Does

it sound complicated? Well, it is. And it has no place here, or in a small sole

proprietor business. So avoid employees

as long as possible. There are several

ways to do that.

Independent contractors.

Be sure you have justification when defining help as independent

contractors, not employees. There is not

problem if the help you get is from a professional

company. In some businesses, such as

agriculture, you can use transient and casual workers. If you can show that this practice is

prevalent in your industry, you can even use the same person practically and

exclusively and still be perfectly legal.

An example would be jockeys and grooms at a horse race track.

Temporary employee companies. They send the employee when you want him (or

her), for as long as you want. You pay

them, and they pay their employee.

Staffing companies. Similar to temporary help companies, but more of a permanent

assignment. Their company is the

employer, and takes care of the wages and taxes.

Any bookkeeping or accounting service. They take care of the payroll and taxes for

you. And any other service you want.

Your spouse. As part of the joint enterprise, not an employee.

In

any event, you should not be spending your time with such mundane, time

consuming work. You’re the boss, the

entrepreneur!

SELF EMPLOYMENT TAX

Don’t’

think that because we’ve kept everything simple, and avoided tax complications

wherever possible, that you’re home free.

The

The

Form SE is what you use to figure that tax.

It has line by line instructions, so it is fairly easy to complete. When the final figure is reached---the tax,

on Line 5---it is carried over to the Form 1040, Line 56.

There

is another little gimmick that sounds good, like they

are giving you back one half of the tax.

Not so.

When

you have figured the tax and carried it forward to the Form 1040, there is one

more line, Line 6. This line has you

take one half of the tax and carry it forward to Line 29 on the Form 1040.

But

this line is not a reduction in tax. It

is merely a credit against gross income.

Thus, if the SE tax was $200, your income would be reduced $100. As the first $12,000 of income is taxed at

ten per cent, this results in a $10 reduction in tax, not $100.

Click here for a sample

of the 2006

Click here for

instructions on how to fill it out.

Please

consult a certified public account for advice.

Dear Student,

J.A. Blazer wrote this

lesson for the school in 2006. He has since passed away. The basic bookkeeping format is still

current, though the dates used in the example are old.

My apologies to non-United

States students - some of the material in this lesson will not be

pertinent. But the basic record keeping

format may help.

There is no quiz or

assignment for this lesson. It is the

last lesson of the course.

Best

wishes,

Eleanor

Blazer