The Business of Making Money with Horses

By

Don Blazer

Copyright

© 2002

Lesson

Two

Know

exactly what you are buying.

There are many breeds of horses.

As reported earlier, there are at least 142 active breed registries in

the

If you are already committed to a certain breed, fine. Stick to it. That breed can undoubtedly make you a great

deal of money, and richer still in other ways.

The price of Arabians once soared as if by magic. Maybe it was.

It is not the same today, but there is still plenty of profit in

Arabians. Morgans

are on a popularity roll. Peruvian Paso

imports and resale prices staggered the imagination a few years ago. Trakehners and warmbloods (imports of almost any kind) are very hot.

Opportunities abound!

Select any breed, and by following the advice outlined for most facets of

the horse business under consideration, you’ll make plenty of money.

However, it would be nearly impossible to gather and compile recent

statistics for each breed, since the data is overwhelming. Therefore, for the purposes

of this course, and because I follow my own good advice (go where the money and

information are most plentiful), I will use race horse (Quarter Horse and

Thoroughbred) statistics most often.

This doesn’t mean there aren’t other racing horses. Standardbreds are a

very big business indeed. Appaloosas are

running, and so are Paints, Arabians and mules.

And this does not mean this course pertains only

to race horses. You choose the breed;

the rules for making money with horses remain the same.

But as much as you might like a non-racing or other breed, and as much

as you might wish it weren’t true, it is true—the greatest flow of cash is in

Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses. These

two breeds command huge prices as race horses.

In addition, they are extremely popular as show horses, trail horses and

sport horses.

I deal in Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses because I like lots of money,

and I like it fast, and I like it easy!

The greatest number of public and private sales are

for Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses.

The largest racing purses are for Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses. The biggest prizes are for jumpers, cutting

horses, reining and western pleasure futurity horses, all dominated by

Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses.

A word to the wise. Horses can make you a lot of money, and

always a lot faster when you ride them among the high rollers and free

spenders. (No matter

what breed or facet of the business you choose, never think cheap! The money is there, ask for it.)

I said you must choose the breed you like

best. So don’t despair. If you choose to stick with any breed other

than a Thoroughbred or Quarter Horse, the game—except for racing—is the same.

There is plenty of money to be made buying and selling weanlings of any

breed. There is money to be made owning

and standing a stallion of any breed.

There is money to be made owning and breeding broodmares of any breed. There is money to be make training horses of

any breed. There are riches to be made

trading all breeds.

The information offered in the following lessons is as applicable to one

breed as it is to another. So stick with

what you like best; you’ll be happier, therefore, eventually richer.

From this point forward, the statistics, the figures, the dollar

amounts, the samples all pertain to Thoroughbreds or Quarter Horses because

they are the easiest statistics to gather and the easiest to verify. (As I told you before, there are no made up

examples in the course; you can check the accuracy of the figures if you’ve a

mind to.) As long as the discussion is

not about racing, you need simply make a mental conversion from Thoroughbreds

and Quarter Horses to the breed you’ve chosen.

Inevitably ALL facets of

the horse business, just as all other businesses, involve BUYING

and SELLING.

Before you can buy and sell horses wisely, you must fully understand

that POTENTIAL is the only thing which makes

a horse valuable. The potential to make money

by winning purses, the potential joy of winning horse shows, or simply the

potential for pleasure found in owning a horse; that is what buyers buy.

Absolute nothing other than potential is important if horses are going

to make you money.

Once you have decided to concentrate your efforts on a particular breed,

you will want to become knowledgeable about the bloodlines, events, activities

and sales associated with that breed.

You must know what is “hot” and what is “not” within the breed

industry. You must know the factors

which create “potential.”

After the horse’s “eye-appeal”, the most important tool for recognizing

a horse’s potential to make money is THE CATALOG.

Every registered or purebred horse, even if he is standing in a backyard

in some out-of-the-way place, has a “catalog page.” The catalog page reports all the facts about

the horse’s family and accomplishments in a particular way. It is your responsibility to understand the

meaning, the sizzle, the weaknesses and the strengths indicated by the

information on that page. You, and you alone, must assess the page and make the final

decision on the horse’s potential to make you money. The people who make money can read “Money” in

the catalog page.

The more you know about a catalog page and the more information on that

page, the better the chances your decision will be profitable.

If you are buying a horse from a

private party, and no catalog page is offered, it is your responsibility to

contact the breed registry and dig out the needed information, then construct

your own catalog page for appraisal and later sales material. Do not buy until you have constructed a

catalog page. In some cases, an offered

catalog page may only be a sentence or two about the horse’s training or

talents. That is not enough. Only by knowing all about the horse’s

pedigree can you determine all the potential areas for profit. And don’t trust a catalog page which can’t be

verified. You can’t verify the

statement: “a sound gelding which will make anyone a wonderful trail

horse.” What you want to see is a list

of accomplishments—such as—won the All Around

Championship, Western World Show, 2002.

Before you buy any horse as part of your businesses, construct a catalog

page so you know exactly what potential you are purchasing.

If you don’t construct a catalog page for every horse you purchase,

you’ll be missing opportunities to make sales, which means missed opportunities

to make money. If you don’t construct a

catalog page for every horse you purchase, you’ll be missing opportunities to

make sales, which means missed opportunities to make money. If you don’t construct a catalog page for

every horse you buy or own, don’t blame me for your losses. It takes time, but you

must develop a catalog page for every horse you buy and every horse you plan to

sell.

While there is nothing wrong with buying a horse from a ranch or

breeding farm, there is usually a greater margin for profit when purchasing the

horse through a sale. For one thing, it

is much less costly to you to have a number of horses to choose from in a

central location. Second, you have no

personal expense in constructing a catalog page. Third, you must be more astute when buying

privately, since you are relying entirely on your own knowledge and

judgment. Most owners and breeders

overestimate the value of their horses, and consequently ask more for them than

they would bring at a sale. At a sale,

you also have the consensus of opinion to back up your appraisal, and that is a

major plus. Seldom will 20 or more other

professional horsemen overbid a horse.

When the bidding stops, that’s about what the horse is worth.

Approximately 20 per cent of the foals born each year, as well as many

older horses, are sold at auction through sales sponsored by private parties,

racing associations, breeder associations, individual breeders, show organizers

or companies exclusively in the horse sale business.

While horses purchased in sales do not necessarily perform any better

than those not in sales, you do have advantages by purchasing at auction.

Many of the sales are “select.”

Select sales require the horses being offered to have been inspected for

conformation and/or to meet some established criteria before acceptance. There are special sales for all breeds and

for various performance talents. In the

case of some yearling sales, the term “select” is almost a guarantee you won’t

get a bad horse. But it is also

practically a guarantee you will have to pay an inflated price. Why do “select” sales create higher

prices? Because the term “select” says

“more potential,” and potential is what buyers buy.

Don’t be afraid of the price of a horse with potential. A high-priced horse with potential will

resell at a still higher price, and a greater profit

for you.

For the best profit margins, it is best to buy at

sales and sell privately.

Catalogs are usually available

several weeks prior to the sale date.

You should obtain your catalog and study it thoroughly. Estimate the selling price of each horse

listed, mark it on the catalog page, and then compare it to the actual selling

price. Good buyers don’t miss by

much. Making a good buy is as important,

maybe more so, than making a good sale.

Studying the catalog carefully will facilitate your inspection of the

horses which interest you. In most

cases, the horses will be on the sale grounds a day or two in advance. In any case, you’ll have a chance to see the

horses hours before they go into the auction ring.

You should have each horse that appeals to you brought from his stall,

walked away from you and back to you, turned and trotted. Determine for yourself if the horse is lame

or travels sound. Ask the handler all

the questions you have concerning the horse’s health, training, disposition,

and his behavior since arriving at the sale.

Don’t believe much of what you are told, but ask! It is too late for questions after the hammer

falls. It is also surprising how much

you can learn from the idle chatter; listen carefully.

And give careful consideration to what you are not told. Most handlers will have a difficult time

lying to you, but remember, they are usually quite

good at not telling the complete story.

If it is a performance horse sale, make sure you attend the

demonstration session.

An auctioneer will often let a horse sell well below its true value, but

smart buyers—and there will be plenty—will seldom let a horse sell way above

its potential for profit.

Buying correctly at sales requires

experience.

You have to be attentive. Many

items on the catalog page may have been corrected, added to or deleted. It is your responsibility to get the

“updates.”

You should know when to start bidding on the horse you want and when to

stop. Don’t be the first to bid; let

other establish the early lower offers.

And stop bidding when the bidding reaches your estimated/acceptable

price. You can’t pay the full price of

the horse’s potential as you see it, or there won’t be room for your profit

margin. You should study how some buyers

“shut out” another bidder, and you should learn to catch sellers “running up”

bidders. Consignors often bid on their

own horses and quite frequently buy them back.

Don’t overpay by being caught in the excitement trap, or by allowing

your desire to get started now overshadow your business sense.

Many sales will have a medication list.

This reports all medications given to any horse in the sale. Be sure you check the list to see if horses

you are interested in have been given medication. If the sale does not have such a list, check

the “conditions of sale” in the front of the catalog to see what rights you

have in case you discover a horse you have purchased has been given a

medication.

Attend some sales just for practice before you actually start buying and

selling.

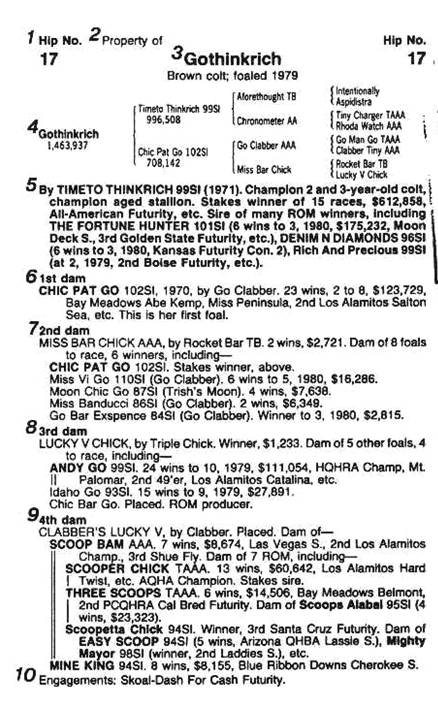

The sample catalog page which follows is typical of the form used in

major sales. Catalogs prepared in the

manner shown instantly give you an idea of the quality of the horse

offered. Some catalog pages are much

more difficult to read due to their organization.

Naturally, the wording in the sale catalog is contrived to present the

best picture of the horse’s pedigree and performance record. Understanding what is not mentioned in the

catalog, and learning to read between the lines will result in an even greater

competitive edge than simply reading what is shown.

You absolutely must understand what the omissions mean.

The catalog normally starts with a title page offering the date and

place of the sale. Several pages follow

which list the conditions of the sale, officials, a map of the sale location

and barns, a credit application, an agent authorization form, consignors,

sires, dams, reference sires, applicable state laws, and other pertinent information

particular to that sale.

Horses to be sold are listed one to a page. To insure fairness in positioning a horse in

the catalog, most sales maintain a certain order, changing each year or each sale. Fasig-Tipton, one

of the nation’s largest sales companies, lists the horses alphabetically by the

dam’s name, each year starting with a different letter of the alphabet.

The sample catalog page lists a Timeto Thinkrich yearling.

(1) The Hip No. refers to the horse’s position

of selling. Number 17 means that this

horse

was to sell

in the 17th position. But don’t count on

it. If you go out for coffee while the

14th hip is selling,

you may find you’ve missed Hip 17 because Hip 15 and Hip 16 were

scratched or

“outs” (taken out of the sale).

(2) The owner, consignor, or agent.

(3) The name of the horse, if named, and the

color, sex, and birth date. If a name

has

been asked for,

but not yet approved, the statement, “Applied For” will appear instead

of the name. When a name has not been applied for, the

color and sex will be

moved up

above the birth date and the horse will be identified as “Brown Colt.”

(4) The name of the colt repeated along with

the registry number, and the pedigree of the

horse

always listed on top, the dam beneath.

The registry number of the sire and dam

will also

be listed, unless one is a Thoroughbred, in which case “TB” will be

stated. The

American Quarter Horse Association

has a complicated system of registration.

Sometimes an owner neglects to apply

for registration, which may cause complications

when buying

from a private party. But in a sale you

can be sure the horse would not

have been

accepted if the registration was not in order.

In the case of unnamed foals,

or older

“appendix” horses, no registration number will appear.

If an asterisk appears in the

pedigree, it means the horse was foreign bred.

Along with the registration system goes a grading system. Most breed associations award points or

titles to competitive horses. For Quarter Horses there may be some combination of “A’s”, or

awards, such as Register of Merit (ROM), or speed index (S.I.). Such designations will immediately follow the

names of horses earning ratings or special awards.

In discussions of pedigrees, there are certain rules which must be

followed. A foal is always “by” a sire,

and “out of” a mare, never the reverse.

Dams, granddams, great-granddams,

always refer to mares in direct descent through the female. They always appear on the bottom line of each

generation, thus sometimes referred to as the “bottom line”, or more correctly,

the “tail-female”.

The top line of each generation, on

the mother’s side, is referred to as the “tail-male”.

Numerical ordering is reserved for successive female sides, the tail-females. Thus the “first dam” is the horse’s

mother. The “second dam” is the

grandmother (the dam’s mother), and the “third dam” is the great-grandmother

(the second dam’s mother).

While the sire’s mother is also the horse’s grandmother, she is never

called that; instead, she is the “sire’s dam”.

It is common to hear a horseman say, “This colt is by Timeto Thinkrich, out of Chic Pat

Go, by Go Clabber.” Thus your attention

is always drawn to the female side of the pedigree. Seldom does a novice investigate the dam of

the sire of a prospective purchase. Such

investigation should always be made as it can be extremely revealing as to

potential, that all-important concept for making money.

(5) A brief summary of the sire’s racing accomplishments,

his foaling date, and his

performance

at stud. Note that this summary is in

bold face type. A great deal more

information

is desirable and available about the sire than can be contained in one

paragraph,

but you will have to research it yourself, and you should.

You

should be well enough versed in your chosen field to know which sires produce

high-priced offspring and which do not.

You should know the stud fee of the sire, and have a good idea of the

annual average selling price of his yearling colts and fillies. You should be aware of colts and

fillies. You should be aware of

performance ability and the disposition of the sire’s offspring.

Remember, the sire, if older, may have sired many good foals, but with

limited space, it is nearly impossible to give more than a short report on his

performance at stud.

The mare most likely will not have a produce record of more than 10

foals, so her entire record can be reported.

You will constantly hear the expression

“black type”. It is an extremely

important part of buying potential.

There are two rules. A stakes

winner’s name will be capitalized in bold face (very black) type. A stakes placed horse’s name will be in bold

face type, but not capitals. If you are

purchasing horses other than race bred horses, the produce record of the bottom

line remains just as important. Mares

which produce outstanding performers in any field have great profit potential,

and so do their offspring. The foals, if

good, will have awards and accomplishments as important as black type.

Even though the sire’s paragraph record is short, much can be

deduced. The principle of listing the

best first is followed. The line “stakes

winner of 15 races, $615,858, All American Futurity,” etc. tells much more than

it says. You can conclude he won more

than one stakes race, but only one of major importance, or it would also have

been listed. At the time of this sale,

The Fortune Hunter was his best foal, and his victory in the Moon Deck Stakes

and his third place finish in the Golden State Futurity carried more importance

than did the Kansas Futurity Consolation placing of Denim N Diamonds. (Of course, Denim N Diamonds later became a

World Champion and a much more important offspring to Timeto

Thinkrich. The

future held more profit potential for Gothinkrich.)

(6) The first dam starts the summary of the

“tail-female” or “bottom line”, giving the

birth date

so you will know the mare’s age. The

dam’s name will be listed in

capitals,

but in light face type unless she is a stakes winner or stakes placed.

If the latter then it will be lower

case letters, but bold face, or “black type”.

In

this case,

the first dam is a stakes winner, so her name is listed in both capitals

and bold

face. Her sire’s name is listed, then

the number of races she won, the

number of

years she raced, that is from two-years-old to eight-years-old,

and the

amount of money she won. You can tell

she won only two stakes, because

two are

listed, then a second place finish in a stakes is reported. If she had won

more than

two stakes, all would have been listed.

The second place finish would

have been

dropped if space for stakes wins was needed.

The catalog then states the horse being offered for sale is this mare’s

first foal. This is important, for not only

must all foals be accounted for, but you must also account for all foal-bearing

years. If a mare has many barren years,

you want to know why. In this case we

know she raced until she was eight (1978), so the mathematics work out. This is the

first possible year that under normal circumstances, she could have a yearling.

A word about the race comment following the mare’s

name. If she raced, the record

will be given. If she was unraced, it

will say so. Only if the mare raced and

was unplaced will no comment be made.

This is virtually true of non-racing horses also. If a mare has performed even fairly well, the

catalog will list even minor awards. If

the mare has not distinguished herself in any field, there will be no

comment. Another case of the un-said

providing needed decision-making information.

The catalog shows Chic Pat Go has

lots of potential.

(7) The second dam offers the highlights of

the female family, but not all the details.

Miss Bar Chick, as you can see

immediately, has not won or placed in a stakes

event

because her name is in light face type.

Money won is also important, but no matter how much she won—it could be

in the hundreds of thousands—she could not earn “black type”. In this case, she had two wins, but only

earned $2,721. This tells you her races

were not quality races, the purses being under $3,000. Purse distribution varies at each race track,

but the winner normally gets about 55 per cent of the purse. Miss Bar Chick was not running for much

money, and her races were won at weak racing locations. You do know she earned a Triple A rating, and this is a minor plus in terms of her

value. With non-racing horses, you must

know what events are considered high quality and what awards create potential

for prospective purchase.

The

next comment is tricky. “Dam of eight

foals to race, six winners…” The catalog

does not tell you how many foals she had, or why they didn’t get to the

races. But it does tell you she had more

than eight foals, and that for sure she had two which did race, but couldn’t

win. Furthermore, as only five foals are

listed, the sixth one to race definitely wasn’t much.

You

should also know the value potential of stakes races or the importance of other

competition.

A

weak stakes win or a victory at a very small show doesn’t carry much value

potential. Any other accomplishment

which does have dollar value will be listed, even if the event is relatively

small.

(8) The third dam, Lucky V. Chick, is reported to have produced five

other foals, four to

race. The five other foals reported do not include Gothinkrich’s second dam, Miss Bar

Chick.

The

catalog only lists three of Lucky V Chick’s foals. Of course, some omissions are necessary due

to limited space, but in this case, Chic Bar Go never won, yet is still

listed. Consequently, you can be sure

the unlisted foal was worse than Chic Bar Go.

Sometimes

after a mare’s name and record, the statement “producer” will be made. This means the mare had produced at least one

winner. It always means just that, no

more, no less.

(9) Fourth dam. If a catalog includes the fourth and fifth

dams, then it is an indication the

previous

dams were not outstanding. Or it may

mean the fourth and fifth dams were

exceptional,

as in this sample. Then too, the fourth

and fifth dams are older and have

time to

produce good foals. Here, the first dam

has had only one foal, so extra space is

available

for the fourth dam, which has produced lots of black type.

You must weigh all the factors in deciding why a fourth or fifth dam has

been included. Personally, I prefer so

much black type or listing of awards and achievements in the first three dams

that there is no room for the fourth dam.

What is “up close,” meaning the “immediate family”, is what has profit

potential.

(10) Here the catalog entries will change

according to whether the horse to be sold is a mare,

a horse, a

weanling or a yearling.

A yearling, and in some cases a weanling, will have “engagements”

listed, telling you to which important races or shows (futurities) the nomination

fees have been paid. Engagements are

usually indicators of profit potential.

A broodmare will have a race record, a produce record, and if she has a

foal by her side, the foal’s birth date and sire’s name. Finally, if the mare has been bred, a

pregnancy status is reported. The words,

“believed to be in foal” are no guarantee the mare is in foal. If you are buying potential for profit, have

the mare pregnancy tested prior to purchase at your own expense. The breeding date and the sire to which the

mare has been bred should be listed.

If the mare was not bred, the catalog

should state, “not bred,” or “open.”

In the case of two-year-olds or older, the training status or race

status should be given, such as “unraced”, “placed twice in four starts”,

“galloped 45 days”. Comments for horses

not intended for racing might include “halter prospect”, “finished in top 10 at

first show”, “loads well”, or “prospective jumper”.

With horses, there is a special

terminology applied to relatives.

Because a sire can have so many offspring, while a mare has only one

foal a year, horses are never referred to as half-brothers or half-sisters

unless they are out of the same mare, but by different sires.

If the horses are by the same sire and out of the same mare, then they

are full brothers, brother and sister, or full sisters.

A foal by the same sire, but out of a different mare, is never a half brother

or sister, but is called a foal “by the same sire.”

A final comment about the catalog page you construct or are given. Black type, awards, and permanent record

achievements never become less than shown, but can constantly be added to by

members of the family.

Hip No. 17 is by a young sire, out of a young mare. (Always potential, as nothing bad has been

proven.) Both have the potential to add

more and better black type or awards to their records. (The sire certainly did.) This may make Gothinkrich

more valuable to some extent at a later date if he remains a colt. (More sales sizzle.) And similarly, his good performance will

positively increase his dam’s value and the value of her subsequent foals.