The Business of Making Money with Horses

By

Don Blazer

Copyright

© 2002

Lesson

Three

Weanlings:

Big Potential for Profits

At first glance, selecting a weanling of any breed seems to be the

biggest gamble of all.

It is not! In fact, it may be your

safest return on investment opportunity.

On the surface, you are dealing with a baby from three to 11 months old,

unbroken except to lead and groom, and essentially untrained. And it is difficult to know exactly what you

will have in a year or more. All this

tends to make a lot of people stay away from weanlings, which means their

price, at sales, is usually less than their true value. (Consider the fact that most weanlings sold

at public auction will bring only about the cost of the breeding fee. Someone other than you paid to have the mare

bred, paid to keep her for the gestation period of 11 months and 10 days, and

paid to keep both the mare and the foal until sale time. Add to all that expense the normal health

care costs, and it is easy to see a healthy weanling at the price of a breeding

fee is a steal.

So immediately you know you have two factors to your advantage. First, no matter what weanling you purchase,

you know that in most cases you won’t overpay if the price is about the same as

the stallion’s service fee. Second, most

of the buyers at a sale are not interested in weanlings, so it is easier for

you to acquire your top selection.

There are a lot of risks between the date of breeding and the time a horse

begins to perform, whether it is racing, cutting, jumping, or driving. With the purchase of a weanling, you are

splitting the cost of taking a horse to the point of performance. The price you pay for the weanling is the

reward the seller gets for assuming the risks from breeding to weaning. If the seller doesn’t make a profit, that’s

his problem. He probably didn’t know how

to have horses make money for him. If

you buy a bargain, for you it is another step to a big percentage return on a

small initial investment.

When you sell your purchase, you will get the reward for assuming the

risks from weaning to point of sale. And

those risks can be minor since the horse is generally under no major stress.

At the time of reselling—with no effort on your part—you have two more

factors which are working to your advantage.

First, yearlings and horses ready to perform almost always bring the

highest sale prices. (The exceptions are

the elite stallions and mares just ready to begin breeding, and stallion or

mare syndications.) Secondly, the high

rollers are willing to pay an extra bonus for yearlings and horses ready to

perform because they are eager to get started; they want action now, and they

want your horse!

If you buy a healthy, sound weanling at a sale, and you care for it

until it is a yearling, or is ready to perform, you will undoubtedly make a

profit of some sort if you sell prior to the time the horse enters any form of

competition.

You may have to tell someone you have the horse for sale, but sometimes,

even that isn’t necessary. I have

purchased weanlings and resold them at a profit in less than three hours. (It has happened more than once when other

buyers realized what a bargain I had purchased.

I took a small profit—large percentage—and they still got what they

wanted at a very reasonable price.)

Weanlings are very salable.

However, you are in the business of having horses make you a lot of

money, so you won’t purchase a weanling just on surface appeal. You will be doing a great deal of

studying. That means you will read every

page of the sale catalog and you will compare every weanling offered with every

other weanling. You will be looking for

potential. (If you are looking for

potential in weanlings not at a public auction, then you will have to construct

your own catalog page. Develop the

catalog page well in advance of looking at the weanlings. You can develop your catalog page by getting

the name of the sire and the dam from the seller, then contacting the breed

association for pedigree information.)

The purchase of a weanling, as the purchase of any other horse intended

to make a profit, is based on potential and no other factors.

To reduce the risks of a weanling purchase even further, most horsemen,

including myself, recommend buying fillies.

If a colt can’t run, win at the big shows, cut cattle, or jump, then both your resale and stud service potential are

gone. Not just reduced, but gone!

You might get lucky and sell the colt

(probably now a gelding) for a private pleasure horse, but you can be sure you

won’t get much. Your possible resale

buyers know the risks inherent with a colt, and so they are not anxious to spend

the big bucks on anything less than a stallion prospect with superior

bloodlines. Even a great-looking colt

without an impeccable pedigree is a risk the majority of buyers at sales don’t

want to take. On the other hand, if a

filly can’t run, jump, or win the big shows, she can almost always produce

foals. (You don’t want her as a

broodmare, because she most likely won’t make you a lot of money, but that’s

covered in another lesson.) But because

she can produce foals, someone will buy her.

Older mares without a record still average a better resale price at

sales than do older geldings or stallions without a record.

That’s taking a negative look at

some good reasons for buying a filly.

But looking at the positive side, the picture is much brighter. Fillies generally bring higher prices at time

of resale. Colts with

weak pedigrees, whether weanlings, yearlings, or two-year-olds, do not command

good prices. A colt with an

average pedigree will bring less than a filly with an average pedigree. Fillies and mares maintain a higher average

sale price at public sales than do stallions and geldings. (At “performance sales—the best performers,

regardless of gender, bring the biggest prices.

They are the ones with “potential.”)

The only time colts demand more than fillies is

when the colts are extremely well-bred, good-looking and have big potential as

a performer; then they are most often the sale toppers.

Of course, there is always the private sale, when almost anything can

happen, and usually does. There is no

ceiling on the price of fillies or colts at private sales. Colts do just as well as

fillies at private sale, as you will note in an upcoming example.

The first example is an unnamed bay filly by the stallion, Call Me Gotta.

This filly, foaled on

Call Me Gotta was a good race horse with solid

bloodlines. As the catalog sheet shows,

he was a Champion two-year-old, stakes winner and earner of $135,000. At the date of the sale, his first foals are

yearlings, so there are no facts about his ability to produce, just POTENTIAL.

The first dam is Hula Skirt, a stakes winning daughter of Tru Tru. Hula Skirt only had an 87 Speed Index, and it

would be best if you could purchase the offspring of a Triple A (AAA) rather than just a Double A (AA) mare. But, had she been Triple A, the price of her

first foal probably would have been much higher, and that would not be good for

you.

The weanling filly offered is the first foal of Hula Skirt, so she has

no proven produce record, only POTENTIAL.

The second dam, Dancing Jacket, is a Thoroughbred, without a speed

index. She was a winner, but not of

much. This will keep the price of the

weanling down slightly. What will

increase the weanling’s price, and her later resale price, is the fact that Dancing

Jacket produced two stakes winners out of six foals. Four of the six foals earned the Register of

Merit (ROM) and one of the six was too young at the time of the sale to have an

established record; more potential.

The third dam did not do much, but the fourth dam was a winner and

produced a stakes winner, and a stakes-placed mare

Fire on Three, who ran out more than $100,000.

Note how well the female side of this breeding has done. The weanling considered is a filly. There is enough black type in the pedigree to

guarantee more sizzle for the potential of the weanling being offered.

This is the kind of pedigree you seek; it is full of potential. It doesn’t matter what breed you are

purchasing. It is all the same—Paints,

Arabians, or National Show Horses—everyone is seeking a satisfaction and the

horse you are looking for must have the potential to provide it. If the catalog sheet shows a lot of winners,

at any event, then you’ve got potential for big profit in purchasing and

reselling any weanling which interests you.

You are hunting for the catalog sheet which offers great potential. You are not looking at horses; you are

looking at the potential they offer.

You’ll look at the horse later.

If the weanling is the daughter of a stakes winner who has produced

stakes winners, the price of the weanling will probably be too high to make her

a good purchase. Too much of a good

thing will make it more difficult to produce a big return on investment without

adding a positive performance record.

And adding a positive performance record can be very difficult. Once you go into competition, if the filly

doesn’t perform exceptionally well, then she will be a bigger profit

loser. This is the case of a

modestly-priced weanling being a better deal.

If the catalog sheets show no black type, no winners, no horses of

merit, then even if the weanling goes for nothing, there is no potential for

profit at a later sale. Skip very cheap

horses. They are cheap because they have

no potential and there is no way short of a miracle for them to attain the

needed potential.

Hip No. 16 at the McGhan Sale sold for the

amazingly low price of $8,000.

The filly was subsequently entered in the All American Select Yearling

Sale at

The performance chart on the filly shows a number of costs involved with

her maintenance and subsequent resale.

The cost of the weanling is a fact.

In any case, even with the high estimated costs, the filly produced a

profit of $16,540 in less than one year.

She produced a return on investment

of 122.8 per cent.

Unnamed

filly by CALL ME GOTTA—Hip No. 16

|

|

Expense |

Income |

|

Cost of weanling |

$ 8,000.00 |

|

|

|

$ 480.00 |

|

|

Veterinarian |

$ 380.00 |

|

|

Farrier |

$ 100.00 |

|

|

Pasture, 10 mos. @ $100 per mo. |

$

1,000.00 |

|

|

Additional hay |

$ 200.00 |

|

|

Grain and vitamins |

$ 200.00 |

|

|

Transportation to sale |

$ 300.00 |

|

|

Preparation at sale |

$ 300.00 |

|

|

Futurity payment |

$ 500.00 |

|

|

Cost of entering sale |

$ 500.00 |

|

|

Selling price received |

|

$

30,000.00 |

|

Sales commission |

$ 1,500.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total cost and expense |

$

13,460.00 |

|

|

Total income |

|

$

30,000.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Net Profit……..$16,540 |

|

|

NET PROFIT………………$16,540

Return on Investment

(ROI) 122.8 per cent.

(Total amount of profit divided by

total investment.)

Now, if 122.8 per cent return on your investment in less than one year

isn’t a lot of money, I don’t know what is.

Considering the initial dollar outlay was only $8,480, and the other

expenses averaged only $440 per month, you have a small investment. But if you took the same total a mount of

money--$13,460—and put it in a treasury bill at the all-time high of 16 per

cent, you would only have earned a profit of $2,153. A 16 per cent return on your investment would

be considered an absolutely phenomenal return today, but it certainly won’t

make you as much money as a 122 per cent return. And if you put the money in a savings account

at 2.5 per cent yield, the only absolute is that you will lose money. Inflation in 2002 was low at only 3 per

cent. In a savings account there is no

risk…..you would have positively lost one-half per cent on your money in

2002. What interest rate are you getting

today on your savings?

Also, keep in mind that you really didn’t have a cash outlay of $1,500

of the $13,460 in costs. The $1,500 was

a sales commission which was paid after the sale and prior to the time the

$16,540 in profit was paid.

If you take off the $1,500, which did not come out of the seller’s

pocket, then the total out-of-pocket expense was only $11,960, making the

monthly cost of maintenance an out-of-pocket expense of only $340 per month.

A ROI of 122.8 per cent on an $11,960 investment in less than one year

sounds almost criminal. But it is a

fact, and it happens, and it is easy to do again and again and again.

If $16,000 in profits is not big enough for you, then you’ll want to go

into business on a little larger scale.

Words of caution—don’t invest your lunch money. Know what you can afford to lose.

You can play the Make Money With Horses game on

any level you like. It is up to you.

Here’s what you can hope to do if you play with more dollars. These examples don’t happen every day, but

fortunately for us, they happen often enough not to be considered uncommon.

Majorie Cutlich

purchased a weanling for $15,000. We

don’t know for sure what she spent in the next eight months to care for the

weanling, but let’s say she spent $10,000.

That makes her investment $25,000.

She sold the weanling after eight months for $270,000, giving her a

profit of $245,000.

That kind of profit and return on investment ought to satisfy anyone.

But how about Donna Wormser

who bought a weanling for $14,000?

Let’s say she also spent $10,000 keeping her horse for 10 months. She resold her $24,000 investment for

$375,000 to make a net profit of $351,000 in less than one year.

If you think you can’t make money—big money—in the horse business, think

again.

Pinhooking is such big business now, that the major breed magazines

include the activities of pinhookers as part of their report on horse sales.

When buyers are optimistic about the

potential a horse offers, expect to see pinhookers making unbelievable

returns. The last time I looked,

pinhookers in the Thoroughbred industry were enjoying a very nice rate of

return of 88.4 per cent. That was up

from 56.8 per cent the year before. This

is the age of opportunity for making money with horses.

Recent reports show weanlings costing less than $10,000 at the major

Thoroughbred sales have resold for an average price of $40,000; that’s a 148

per cent return on investment. Weanlings

selling between $10 and $20,000 were returning 118.6 per cent. Now just so you will realize it is not all

roses, weanling selling for between $30 and $40,000 returned only 16.9 per cent

that year.

Here’s another great return, except it is calculated on a very small

budget.

This example is a colt. I don’t

recommend buying weanling colts for resale at sales, but they do make

money. This colt was not resold at a

sale, but was sold privately.

Nashville Shadow was purchased at a sale. His pedigree did not have as much potential

as I would normally like, but it had some.

The colt was an outstanding individual conformationally,

which added substantially to his potential.

The first dam was a stakes-placed mare that

had produced five foals to race. Three

were winners, one of which was stakes placed.

The mare, however, was an older mare—17 years old. She obviously hadn’t produced as much as we

would have liked, and it wasn’t likely she would produce more.

What made me buy this weanling was the fact the mare had a very

good-looking yearling colt which sold prior to the full brother weanling. When the yearling brought an excellent price,

the weanling suddenly had a lot more POTENTIAL!

|

|

Expense |

Income |

|

Cost of weanling |

$ 1,300.00 |

|

|

|

$ 78.00 |

|

|

Veterinarian |

$ 300.00 |

|

|

Farrier |

$ 100.00 |

|

|

Board, 7 mos. @ $135 per mo. |

$ 945.00 |

|

|

All American nomination fee |

$ 50.00 |

|

|

Total cost and expense |

$

2,773.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sold privately |

|

$

6,500.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Net Profit……..$3,727 |

|

|

NET PROFIT………………$3,727

Return on Investment (ROI) is 134 per

cent.

Jet charger had proven himself to be only a

fair sire. He produced runners, but his potential—at

12 years of age—was limited.

Nashville Shadow was worth a risk only because he was a good-looking

colt, his selling price was low--$1,300, the catalog sheet shows some black

type and possibilities, and he had a yearling brother ready to go into race

training, which could add some new sizzle to the potential. Still, this type of purchase should not be a

high priority. It was a legitimate

purchase by the rules, but not a great buy.

The example is included only to demonstrate that weanlings frequently

offer big rewards on small investments.

Nashville Shadow was entered in the All American Futurity, a million

dollar race, to provide some sales appeal.

The initial cost of entry was only $50, so the investment was minor in

comparison to the “sizzle.”

The colt was not advertised, but was shown to normal barn traffic. One such person liked the colt and purchased

him for $6,500. The profit on the colt

was $3,737 and the return on the investment was 134 per cent. Not bad for a horse held only seven

months. Not bad, and yes, lucky. But you make your own luck.

When you consider the total investment was only $2,773, the profit was

considerable.

The final example is included to show what happens when the rules are

not followed.

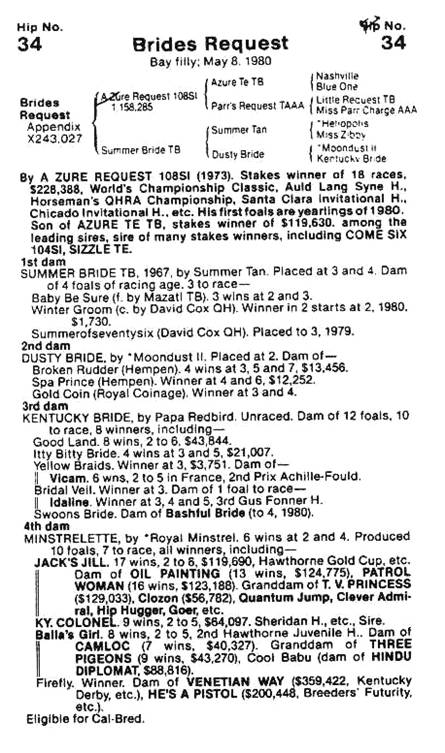

Brides Request is a filly by a young stallion, A Zure

Request. As shown by the catalog sheet,

A Zure Request did very well as a race horse, and has

the pedigree to be a good sire—that’s potential, and it’s what you’re seeking.

The first dam, however, puts the purchaser of this filly in

trouble. A Thoroughbred, Summer Bride

was not a winner. She only placed at 3

and 4, which proves she wasn’t a good race horse. There is no potential there.

As a producer, Summer Bride is the dam of four foals, three of which

went to the races. Two foals were

winners, and one of the two was a Quarter Horse, the same as Brides

Request. That shows an ounce of

potential. But even a pound of cure

won’t make up for the lack of “sizzle” come sale time.

The second dam, Dusty Bride, was not a winner, although she produced

three winners. But do three winners add

up to potential? In

this case, no. None did

much. And earnings of $13,456 for a

Thoroughbred are very small.

The third dam shows no potential either.

And by the time you get to the fourth dam, even the black type there is

too little, too late.

Brides Request sold for $2,000 as a weanling, and the cost of keeping

her until sale time as a yearling were minimal.

The total cost and expense was $5,495.

The selling price at the All American Sale was $6,500, and was

predicated on the potential of the stallion, A Zure

Request. (A Zure

Request later proved himself the sire of some speed, and gained modest

popularity.)

The net profit on the weanling filly was $1,005, and the ROI was 19 per

cent.

Granted 19 per cent return on an investment of only $5,000 is pretty

good in comparison with many other types of businesses. But it was somewhat risky because the total

potential was weak. The

potential of the stallion and the fact that the weanling was a filly—two of the

rules to follow—are the only two things which saved this investment. Pass when the weanling offered doesn’t show

excellent potential on the catalog sheet.

BRIDES

REQUEST

|

|

Expense |

Income |

|

Cost of weanling |

$ 2,000.00 |

|

|

|

$ 120.00 |

|

|

Veterinarian |

$ 300.00 |

|

|

Farrier |

$ 100.00 |

|

|

Board, 10 mos. @ $135 per mo. |

$

1,350.00 |

|

|

Transportation to sale |

$

300.00 |

|

|

(Owner

groomed and showed |

|

|

|

horse - no

outside costs) |

|

|

|

All American Futurity payment |

$ 500.00 |

|

|

Cost of entering sale |

$ 500.00 |

|

|

Selling price received |

|

$ 6,500.00

|

|

Sales commission |

$ 325.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total cost and expense |

$

5,495.00 |

|

|

Total income |

|

$

6,500.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Net Profit……..$1,005 |

|

|

NET PROFIT………………..$1,005

Return on investment (ROI) 19 per

cent.

Weanlings are good profit makers, and often require a small investment

and very little physical work. But you

must follow the rules.

Rules

for Pinhooking

1. Purchase fillies.

2. The weanling must be by a well-bred stallion who has proven himself a better

than average

performer, but does not yet have a long record as a sire.

3. The first dam must have proven herself an

excellent performer, or an excellent

producer. The produce of an average first dam should be

passed.

4. The second dam must also be a performance

winner, or the producer of

performance

winners. The second dam is still very

important when seeking

potential. She must show it. If the second dam is stronger than the first

dam,

that is even

better. But a strong dam can never make

up for a weak first dam.

Do not fall in to the trap of thinking you

can slip one through and make a big

profit based on a

strong second dam. Smart buyers just

won’t pay the price, and

the less than

bright buyers only purchase cheap horses.

5. The third and fourth dams are not too

important. A lack of black type or

performance

record will not hurt. Third and fourth

dams, however, should have

produced

something. If they haven’t produced,

then the entire line lacks potential.

6. The weanling must be sound and without

obvious injury when purchased, and when

resold.

Potential is the key! The

weanling being resold as a yearling will make money if she is good-looking, is

by a solid, yet unproven sire, and is out of good-performing and/or producing

first and second dams.

If you don’t follow these rules, don’t blame anyone buy yourself if the

weanling doesn’t make money.

And if you say it’s too hard to find

weanlings which meet all the requirements, you are wrong. It’s not too hard, it’s just hard. That’s one of the reasons buyers aren’t

making a log of money with weanlings.

Pass the ones which don’t measure up in conformation, blood, and

potential. It is always better to pass

500 than to buy one bad one. If horses

are going to make you a lot of money, then you’ll have to put in a little

effort and a lot of patience.

Don’t buy because you are caught up in the excitement of the sale. Don’t buy because you want some action. And don’t buy hoping your normal good luck

will make things turn out well.

If the dollar amounts in the examples are not big enough to suit you,

just play with bigger bucks. (All breeds

have the same potential for enormous returns on small investments.) You can play at any financial level. And you can play with more than one horse, so

you can double, triple or quadruple your income anytime you choose.

The scale on which you decide to get started is completely up to

you. The important thing is to get

started. It is a business, and time is

money, and you could be making a lot of it, now!