Lesson 7

Digestive

System and Colic

Digestive System

CHOKE

Obstruction of the esophagus. This is an emergency situation.

Blockage

could be caused by feed, treats, lack of water (especially in the winter) allowing

for feed blockages, chunks of apples or a corn cobs, very coarse hay.

Clinical signs: Coughing, gagging, discharge

of saliva or feed from nose and mouth, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and ptyalism (excessive salivating).

The

horse will have difficulty breathing. But unlike humans will still be able to

breathe.

Anxiety, trying to “retch” and

stretching/arching of the neck.

*

Care must be taken when examining the horse as a drooling horse may have

rabies, which is transferrable to humans.

What to do: Call a veterinarian. Do not

delay in calling the veterinarian, as permanent damage to the esophagus may

result. Walk the anxious horse, or let

him stand quietly, and allow the horse to lower his head. Remove feed. Follow

veterinarian’s advice regarding access to water.

Do

not use a water hose to try to dislodge the obstruction. Carefully clean out horse’s mouth if

possible. Massage the left side of neck

over the obstruction (lump). Try to keep

the horse calm.

What the veterinarian will do: Tranquilize the horse. Pass a stomach tube in an effort to gently

dislodge the obstruction. The

veterinarian may give medication to help the esophagus muscles to function more

efficiently and give the horse time to get the obstruction through. Antibiotics

and anti-inflammatory agents are usually indicated.

If

the horses does not improve lavage of the esophagus will be the next step. This requires sedation and the insertion of a

nasogastric tube through which water will be flushed to try to loosen the

blockage. The horse’s head must be kept

low to prevent water from getting into the lungs.

All

horses should be fed a soaked complete feed for 7-14 day, decreasing the chance

of a second choking episode. Horses with

damage to the lining of the esophagus will need to be kept on the soaked

complete feed diet for at least 60 days.

Horses that have repeat issues of choking may have to remain on the

soaked complete feed diet for the rest of their lives. There are surgical procedures that may help.

EQUINE GASTRIC

ULCER SYNDROME (EGUS)

Foals

as well as adults can be prone to developing stomach and intestinal

ulcers. Newborn foals may develop

perforating peptic ulcers because the mucosa is not fully developed. By the time they are a few weeks old the

ulcers should be healed unless stress and poor management has been a part of

the foal’s life, in which case medical intervention is required. Most foals

will not exhibit symptoms of ulcers.

Stress

plays a major role in the cause for all ages of horses. Performance horses are at greater risk due to

stress of training and performance.

Performance

horses with high grain – low forage diet are very susceptible to ulcers. The chewing of forage produces salvia, which

acts as a buffer – protecting the delicate lining of the stomach. Horses on pasture or having access to a

constant source of forage rarely get ulcers.

Studies have also shown

exercise can cause ulcers, especially if the stomach is empty. A common practice among racehorse trainers is

to not feed a racehorse for 24 hours prior to a race. During strenuous exercise the stomach

contracts, pushing the contents up into the esophageal region where there is no

protection from the acid. Tests have

shown the presence of food in the stomach will prevent the acid from being

forced into the upper unprotected area. Withholding forage will cause more

problems than the goal of achieving better performance.

NSAID’s

(Bute or banamine) can also

be a cause.

Ulcers

can also be caused by another illness, due to secondary stress. Stall

confinement and a change in routine.

Clinical signs: adult horses: colic, lack of

appetite, poor body condition score, irritability, poor performance, dull

appearance

In

foals: Most foals will not show symptoms, but be alert for: no interest in

nursing, diarrhea, ptyalism (excessive salivating),

laying on the back with stomach exposed (dorsal recumbency)

and bruxism (grinding of teeth).

Diagnosis: The only way to definitely

diagnose an ulcer is with an endoscope.

Treatment and control: Change of management is the

first step. Treatment with drugs will

not be effective if the cause is not eradicated. Horses that must be kept in stalls should be

offered free choice hay. Grazing and

pasture turnout is the best way to help prevent the formation of ulcers. New studies show some alfalfa hay in the diet

may help prevent the development of ulcers, due to the calcium content acting

like a buffer against the acid.

Drugs: The objective of drugs

is to lower the acid and/or protect the sensitive lining by creating a coating

agent.

Ranitidine,

cimetidine, famotidine – Histamines (H-2 blockers) competes with the histamine

that stimulates the cells to produce acid. Used to treat gastro-duodenal

ulcers. Effectiveness is questioned, best results when horses are removed from

training/competition and the stressful environment. Not approved by the FDA,

but used off-label.

Omeprazole

– proton pump inhibitor; inhibits and shuts down the

production of acid. Approved

by the FDA. Horses can remain in

training. Most effective treatment, but more expensive.

Treats and prevents.

Antacids

- works to neutralize the stomach acid already present. Not proven to heal or

prevent ulcers. High and frequent dosages are recommended.

COLIC

Strangulating vs.

non-strangulating colic.

Conditions

of the small intestine that cause acute colic may be classified as simple

non-strangulating obstructions and strangulating obstructions.

Simple

obstructions occur when intestine is blocked, without concurrent vascular

compromise. A simple obstruction allows the buildup of intestinal contents. The

intestine becomes distended due to the material being blocked from advancing.

Minimal tissue damage is the result, unless the obstruction is allowed to remain

and becomes worse. Examples of a simple obstruction may be ascarids,

feed, or foreign bodies; and obstruction by cancerous growths, abscesses or

adhesions. If the mass cannot be moved

by the use of fluids and mineral oil, surgery will be required. Speed in

treating the horse is imperative.

Strangulating

obstructions can occur when a simple obstruction is not removed. The blood and oxygen supply is cut off

resulting in the severe damage of the intestine. Bacteria and endotoxins are allowed to invade

the intestine.

Strangulating

colic can also be caused by volvulus (twisting) of the small or large

intestine.

When

the intestines are twisted or displaced surgical correction will usually be the

only way to save the horse. It is usually not possible for the vet to

determine, during the early stages of the colic, whether the horse will require

surgery or not in order to cure the colic. The vet will monitor the horse

closely using various diagnostic aids to determine whether surgery will be

necessary. The costs of colic surgery

can run upwards from $5,000, including pre and post-surgical care. If surgery

is contemplated it is wise to understand your horse’s chances of survival. The

veterinarian should be able to give you an educated guess as to the chances of

the horse surviving the surgery.

Mild

colic signs:

a.

Spasmodic colic – spasms of the intestines causing mild abdominal pain.

b.

Simple gas colic – Gas distention of the intestines causing abdominal pain.

c.

Impaction colic – feed which impacts and causes a temporary lack of movement

along the digestive tract, also causing abdominal pain. This includes sand accumulation from feeding

in areas where soil is sandy. Blockage due to ascarids, or the mass removal of the parasite when

deworming.

Any of the above normally

initiates as mild colic signs, but depending on the amount of gas buildup or

the severity of the spasms, can show up as significantly painful to

horses. Any colic in the horse should be

considered an emergency, because it is much easier to prevent colic from

becoming more severe by treating it appropriately as soon as possible.

Prevention:

1.

Feed at same time everyday.

2.

Examine your feeds closely and never feed spoiled feed or moldy, musty hay.

3.

Keep feed amounts and quality consistent.

Increase feed amounts gradually, and change feed types gradually.

4.

Offer horses clean fresh water continuously.

5.

Good horse management practices.

6.

Regular psyllium in the diet (1 –2 cups per 1,000 lbs daily for 1 week a month)

will prevent sand accumulation in the intestinal tract and prevent sand colic.

7.

Maintain a good deworming program, especially for young horses.

What

to do before the vet comes:

Keeping

the horse up and moving is helpful in easing the pain and preventing the horse

from rolling. If the horse is lying down

and is still, forced walking is not a necessity. Follow the instructions of

your vet.

What

the vet will do:

An initial exam to try and

determine the nature of the colic.

Usually pain relievers, antispasmotics, and possibly

mild sedatives may be used to control the pain.

The vet will most likely pass a stomach tube in an attempt to relieve

any gas accumulated in the stomach, or possibly even siphon accumulated fluids

off the stomach. If an impaction is

suspected, mineral oil or other lubricants may be administered into the stomach

via the stomach tube. Rectal palpation

may be performed to aid in diagnosis.

Other

Specific Types of Colic

Blister Beetles

Blister

beetles are found in alfalfa hay occasionally.

They are very toxic to the horse and cause a deadly colic when ingested.

These blister beetles are trapped in the hay during the baling process.

Enteroliths

Hard concretions that can form

in the intestine and cause blockage of the intestinal tract.

Enteroliths have been linked to pastures

or water that is high in calcium or phosphorous (high alkaline sources of water

or feed). These stones can also occur from the horse ingesting a piece of

string or nylon as may be found in halters, lead ropes, hay bags, and even old

tires used as feed tubs.

Prevention

in high alkaline areas of the country consists of adding vinegar (acidic) to

the diet (4 oz per day).

DIARRHEA

Although

horses will develop a loose stool on certain occasions, when a horse has a

persistent or a foul smelling watery diarrhea, you should consider it a

definite emergency.

Colitis

- Inflammation of the colon (large intestine) which can be caused by bacteria

(like salmonella), Potomac Horse Fever, stress, disruption of the balanced

microbial population in the digestive tract, parasites or other causes.

Vital

signs should be taken and communicated to the vet during the initial call.

The

vet will examine the patient, probably take blood and other laboratory samples,

and may initiate treatment with re-hydrating fluids as well as other

therapies. Treatment must be implemented

as laminitis is possible.

Keeping

the horse hydrated is one of the most critical parts of the treatment in cases

of colitis, because the horse can dehydrate so rapidly when they develop

diarrhea.

Prevention: In areas where Potomac horse fever is a

factor, vaccination is wise. Regarding other forms of infectious diarrhea, the

horseman must keep in mind that over work or other forms of physical stress

(physically overstressing the horse’s system) can lower the horse’s natural

immunity and can lead to changes in the colon which could lead to colitis. Avoid the over use of certain antibiotics or

anti-inflammatories (bute or

banamine). Make all feed changes gradually, this

includes forage. Provide clean water.

Internal and

External Parasitic Diseases

and

Their

Prevention and Treatment

Equine Internal Parasites

|

Parasite |

Site of Infection |

Life Cycle |

Symptoms |

Treatment |

Control |

|

Habronema (Stomach

worm) |

Stomach |

Typical, but fly involved |

Typical & wound contamination |

Ivermectins, moxidectin , Strongid, or benzimidazoles |

Good Mgmt., Fly control |

|

Ascarids (large

roundworms) |

Small Intestine |

Typical & larvae migrate through

lung & liver |

Typical & Young horses – cough,

snotty nose, impaction |

Same as above |

Good Mgmt. |

|

Small Strongyles |

Large Intestine |

Typical & cysts in mucosa |

Typical & Colics

in spring when cysts mature |

Same as above moxidectin

and Ivermectins effetive

against cysts |

Good Mgmt. |

|

Large Strongyles

(Bloodworms) |

Large intestine |

Typical & larve

migrate through intestinal blood vessels |

Typical & anemia and thromboembolic

colic |

Same as above moxidectin and Ivermectins effective against migrating larvae |

Good Mgmt. |

|

Threadworms |

Large intestine |

Typical & mares milk to foal |

Foal diarrhea (7 days to 3 weeks of

age)` |

Ivermectins, moxidectin, strongid, benzimadazols |

Good Mgmt&

Prevention- Ivermectins or quest to

mare day of foaling |

|

Pinworms |

Large Intestine |

Typical & eggs sticky found on

rectum and anus |

Typical & tail itching and

rubbing |

Ivermectins, moxidectin, strongid, benzimidazoles (can give when see tail rubbing) |

Good Mgmt. |

|

Bots |

Stomach |

Part of life cycle of Bot Fly

(larval stage in stomach) |

Typical & see bots in manure,

Seasonal – Bot eggs (nits) on chest and upper leg hair |

Ivermectins, moxidectin, in the late fall or early winter |

Fly control. Razor off nits. Warm

water to nits |

|

Tapeworm |

Sml. Int. |

Typ.&mite |

Colic |

Praziquantel, pyrantel pamoate (cestocidal dose – double nematode dose), late fall or

winter |

Good Mgmt |

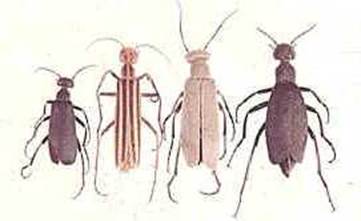

Bots

Typical

Life Cycle

– Adults in intestines pass eggs into manure; eggs hatch and become infective

larvae, ingested by horse and become egg laying adults in intestines.

Typical

Symptoms

of severe infestation- poor hair coat, pot belly, poor doer, unthrifty, poor

appetite, no energy, anemia, pale mucous membranes.

Good

management practices

1.

Well

fed horses have fewer parasite problems.

2.

Clean

up manure: A. from stalls daily B. from

paddocks every other day C. from

pastures regularly (if possible).

3.

Pasture

rotation.

4.

Good

deworming program (deworm all horses on premises at same time).

5.

Strongid C (daily dewormer)

6.

Don’t

feed off the ground.

7.

Conduct

regular fecal egg counts

8.

Manure

management:

A.

compost pile (heat

kills worm eggs)

B.

Haul off manure

C.

manure spreader – exposes eggs to sun (hot and dry) which kills eggs during

certain season

D.

horses won’t graze where they have droppings.

FECAL EGG COUNT (FEC)

Due

to internal parasites developing resistance to strongyle

and/or ascarid deworming products it is not

recommended to deworm horses that do not carry a worm burden.

Horse owners or stable managers should collect a small amount of manure, secure it in an airtight container. The sample must not be allowed to freeze, but

should be refrigerated and sent to the lab within 12 hours of collection. At

the lab, a technician mixes the manure with solution. The worm eggs float

to the top. A gram of the specimen is examined under a strong microscope

and the eggs per gram are counted.

Most labs just count small strongyles.

Large stronglyles, in all stages, are easily

controlled. If the small strongyle population

is controlled then so goes the large. If a horse has a high population of

small strongyles, he generally also has ascarids.

Using the FEC to detect tapeworms is not reliable. Tapeworms infrequently

shed segments which may contain eggs (needed for detection). In

comparison, other intestinal worms shed eggs almost continuously.

The lab will report the small strongyle egg

count as eggs per gram. The FEC scale is: less than 200 eggs per gram -

low; 200-500 eggs per gram - medium; 500 plus - high.

Horses with a FEC of 200 or more are candidates for colic, unthriftiness

and anemia. These horses are also contaminating the pasture and keeping

the parasite growth cycle active.

Conducting a second fecal egg count 14 days after a dewormer

has been administered will tell you if the product worked. A low fecal

egg count reduction (FECR) can indicate parasite resistance to the active ingredients

in the product. A low count may also indicate the product was old or not

enough administered. The horse should be dewormed with a product that

uses a different chemical class as the active ingredient. Then another

FEC conducted within 10 - 14 days.

Horses with a steady fecal egg count of less than 200 eggs per gram may only

need to be dewormed twice a year. Deworming horses that do not need to be

aggressively dewormed is expensive and can create resistance to dewormer ingredients.

Many vet clinics will do a fecal test to detect worms, but not count the eggs

per gram. In order for the test to be beneficial you must request a

count.

Horses

will still need to be dewormed for bots, pinworms and tapeworms, if so

indicated.

For a more in-depth study of fecal egg counts and the American

Association of Equine Practitioners Parasite Control Guidelines, please go to: http://www.aaep.org/custdocs/ParasiteControlGuidelinesFinal.pdf

DEWORMING PROGRAM

Readily Available Dewormers:

Ivermectins: Eqvalen, Zimecterin, & Quest

- These will get all worms and bots.

Benzimidazols: Anthelcide, Panacur - These will get everything, but the bots

Pyrantel: Strongid, Strongid C – These products will get everything, but

bots. They are also available as a daily

feed additive for constant control of parasites (except bots).

Praziquantel:

This is a recently available compound that controls tapeworms. It is found as an addition to Ivermectin wormers (Zimecterin Gold),

Quest (Quest Plus) and other

combinations, as well as by itself in some products.

Deworming

Schedules – If not conducting fecal egg counts

Foals – Every 2 months until 1 year of age then

deworm as an adult horse.

Adult Horse – Every 3 months - fall (after first

frost) and spring. Deworm for bots and all roundworms. (Quest or ivermectins)

Summer and winter – deworm for

all roundworms. (Strongid,

pyrantel, benzimidozoles)

Daily worming - Strongid

C - Still must worm for bots fall and spring.

Care must be taken when worming

a heavily infected young horse. Large roundworms may cause impaction colic.