Lesson 3

Common Hoof

Disorders

Sole Bruises

Definition – Sole bruises

are actual bruising (bleeding) under the sole surface of the horse’s foot.

(Remember – the sole is not intended to be a weight bearing part of the bottom

of the foot, it is normally concave and shouldn’t hit the ground surface with

full force.)

Symptoms – There is some

sensitivity over the bruised area especially if hoof testers or some other

pressure is applied over the bruised area. It doesn’t always cause a noticeable

lameness. Paring away of the sole in the

bruised area will show discolored (bluish-black) sole .

Causes – Concussion to the sole

by hard objects such as large rocks, gravel or hard road surfaces. Unleveled or poorly fitting

horseshoes can also cause sole bruises.

Location – the under part of

the sole surface of the hoof

Prevention – Shoeing the horse

will help protect the sole. Keep the sole of the foot in a healthy

condition. Pads are used when the sole

is flat or not very tough.

Treatment – Treatment would

consist of Epsom salt soaks, toughing up the sole with hoof conditioners

(iodine or koppertox) and the use of pads for

protection of the bruised area, if the horse is to continue to be used.

Corns

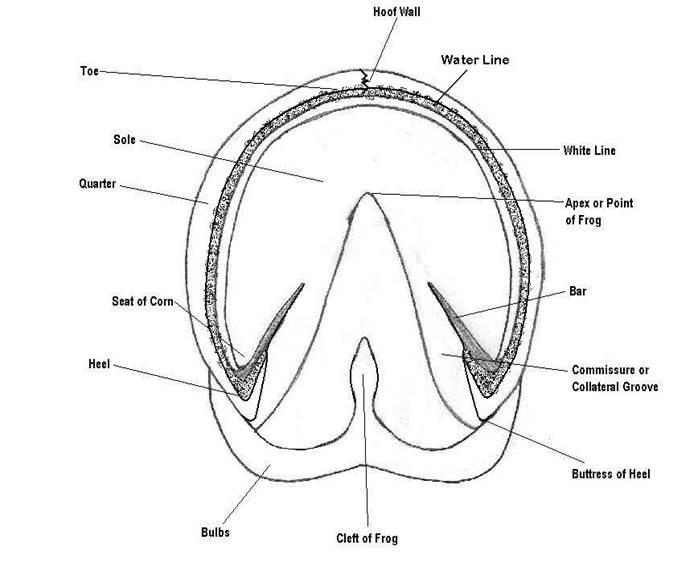

Corns are a sole bruising which

occurs in the “seat of corns,” the area at the heel formed by the angle of the

bars of the heel. See foot chart. The

bruising is usually due to a shoe that has been left on too long. The foot

grows back and the end of the shoe will put pressure on the sole area at the

angle of the bar. When the horse walks or moves on the shoe in this position,

it puts pressure in an area that is not designed to bear weight so it will

easily bruise.

Hoof Abscess

Definition – A hoof abscess in

an infection or pus pocket on the underside of the sole or somewhere within the

sensitive part of the hoof.

Symptoms – A severe lameness,

the horse is normally reluctant to put any weight on the affected foot until

the abscess breaks and drains. There is heat in the affected foot, especially

where the abscess is located, and hoof testers or thumb pressure over the

abscess will illicit a pain response in the horse. Oftentimes there will be

swelling in the pastern area, and a strong digital pulse can easily be felt in

the affected foot.

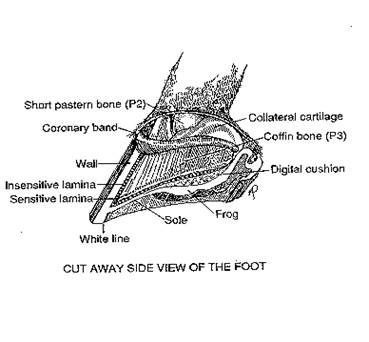

Causes – A sole bruising, if

severe enough, can develop into a hoof (sole) abscess. The most common cause of

the hoof abscess is a puncture wound of the sole or frog that penetrates into

the sensitive tissue. White line disease or other separations of the hoof area

that allow bacteria to penetrate into the sensitive structures of the hoof can

cause a hoof abscess. Abscesses can also develop in the space that is created

when the coffin bone rotates during a severe case of laminitis. “Quicking” a horse

(driving a nail into the quick, or sensitive part of

the foot) can cause an abscess.

Location – An abscess can occur

anywhere below the hoof capsule in the sensitive part of the foot, but usually

follows the path of least resistance, so many will travel to the white line,

then break out at the coronary band.

Prevention – Keeping the foot

healthy, clean and dry, will help prevent hoof abscesses from developing. If the horse is “quicked,”

or gets a puncture wound, paring it out with a hoof knife, or treating it

immediately with strong iodine may help prevent a hoof abscess from

developing. Putting the horse on preventative antibiotics may also be

warranted. Seek advice from your veterinarian anytime you see blood coming from

a hoof puncture.

Treatment - Hot Epsom salt soaks will help draw

the abscess out of the hoof, as will a poultice application under a hoof

bandage. Both procedures should be

used. Consult your veterinarian if the

abscess does not resolve within a few days.

Antibiotics may be necessary. Once the abscess breaks and drains, you

should still soak and pack for a few days, treating the open area with

something like strong iodine to toughen the area and close the opening.

Hoof Cracks

Definition – a vertical crack in the

hoof wall. Cracks can be superficial (not penetrate the sensitive lamina) or

deep (penetrate the sensitive lamina and cause blood to appear at the surface.)

There are three “named” types

of hoof cracks.

A “sand crack” originates at the coronary band and

continues toward the toe of the horse, running parallel to the horn tubules,

either completely or partially to the edge of the hoof. These cracks can be thought of as a fracture

of the hoof wall.

A “horizontal crack” is parallel with the coronary band and

grows out with the hoof.

A “grass crack” originates toward the toe and runs parallel

to the horn tubules toward the coronary band.

These cracks can be thought of as a “split” in the hoof wall.

Cracks are identified by location, and are called toe,

quarter or heel cracks. On the bottom of

the foot, or solar aspect, cracks usually go across the bar or sole and radiate

from the apex of the frog, and then are called, “bar” or “sole” cracks.

Symptoms – If the crack is

superficial, there are no lameness symptoms, but if the crack penetrates into

the sensitive tissue of the hoof, blood and pain will be noticed.

Cause – Dry, brittle hooves are more

prone to hoof cracks. Cracks can also occur from imbalanced feet or uneven

weight bearing. A deep wire cut or laceration into the conorary

band will produce a defect in the coronary band where the hoof grows from, and

a crack will always grow down from there for the rest of the horse’s life.

Location – the location of the hoof

crack is usually designated by toe, quarter or heel crack. They can start from

the ground surface and travel up, or they can start from the coronary band and

travel downward.

Prevention – Good hoof management

practices will help prevent hoof cracks. Keeping the hooves

healthy and pliable. Proper balancing and shoeing will also prevent hoof

cracks.

Treatment – The important aspect of

treating hoof cracks, is to stop the crack from

spreading, stabilize it the best you can, and promote healthy hoof growth to

allow the crack to grow out as quickly as possible. The crack can be grooved

with a horizontal groove in the hoof wall at the end of the crack. This might

keep it from spreading, especially if it is not a deep crack. Usually a horse-shoer and /or a Veterinarian will be involved in the

treating of a hoof crack. They will use shoeing (shoes with clips to stabilize

the crack, or a shoeing technique to take direct pressure off the crack) . OR they may use staples, or other hardware (screws and

plates) or even special acrylic bonding material to repair the crack. (Remember

horses’ hooves grow down about 1/4 to 1/3 of an inch a month). Trimming or re-shoeing should be done every

four weeks until the crack has been resolved.

Navicular disease or syndrome (CAUDAL HEEL SYNDROME)

Definition – Navicular disease, or as

it is more popularly referred to by veterinarians today, “caudal heel

syndrome”. It is a chronic (long

standing) disease involving inflammation of the navicular bone and navicular

area of the front limbs.

Symptoms – Navicular disease usually

shows as a mild to medium lameness condition of the front limbs, usually one

front being worse than the other. The horse is normally reluctant to place his

heels to the ground at a trot, and will stumble and short stride. A head bob is

usually noticeable at the trot (head goes up when the sorest foot hits the

ground) especially when going in a circle. When standing, a

horse with navicular pain may point (place one front foot slightly ahead of the

other, therefore relieving the pressure on the navicular bone). X-rays

of the navicular bone will show spurring of the bone and /or holes in the

navicular bone (lollypop looking holes). Although occasionally a horse with

clinical navicular disease will have clean x-rays. In this case the explanation

is usually that the pain is associated with the soft tissue structures of the

navicular area. (This is still considered to be navicular disease)

Location – Navicular bone, navicular

bursa, and deep digital flexor area over the navicular bone. Seen almost exclusively in the front feet. Usually both

front feet are involved, one worse than the other.

Cause

- Usually seen in older horses as a wear and tear type of damage, seen in

horses with small hooves, short, straight pasterns, or low heels and long toes.

Concussion over this navicular area below the heel is the main cause. Heredity

may play a role, and horses as young as two-years old can start showing

symptoms.

Prevention – Short, straight pasterns

and small feet can predispose a horse to navicular problems because of the

increased concussion to the heel area and navicular area of the foot over time.

Purchasing horses with adequate size of foot in relation to their size, as well

as those with good pastern conformation, and normal and equal hoof to pastern

axis, as well as keeping these horses shod in the correct way, can prevent you

from having problems with navicular disease in your horses.

Treatment – Corrective Shoeing or

trimming – High heels, short and rolled toes . Bar

shoe, bar across the middle third of the frog.

Medical management: Bute - pain management. Isoxuprine tablets in the feed will help increase blood

flow to the navicular area.

Laminitis

Definition – Inflammation of the

lamina of the feet.

Causes:

1.

Overloading the digestive system with carbohydrates and starches; overfeeding

grain, lush pasture or rich hay are a few examples. This is the most recognized cause of

laminitis.

Horses

diagnosed with Cushing’s syndrome, Equine Polysaccharide Storage Myopathy,

abnormal thyroid levels or are insulin resistant must be offered diets which

avoid carbohydrates and starches.

2.

Obese/overweight condition.

3.

Retained placenta.

4.

High fever, infection from disease.

5.

An allergic reaction to a vaccine or medication.

6.

Exposure to black walnut shavings.

7.

Excessive cold water ingestion when an excessively hot horse is not cooled out

properly.

8.

Road founder – overwork on hard ground.

9.

Overexposure to cortisone type drugs

All

above basically encompass over stressing a horse due to poor training or

management decisions. (Pushing a horse over what his system can tolerate) Horse

must become slowly accustomed to changes in things like feed, or exercise)

Three Phases of Laminitis:

DEVELOPMENTAL

PHASE – This

is the period when something occurs to the horse or pony leading to the

inflammation of the laminae. It is sometimes

very difficult to recognize a horse in the developmental stage of

laminitis. Observation and awareness is

the key – know if your horse has had access to the feed room, excessive amounts

of lush grass, has been vaccinated recently, has had a high fever, or any of

the other causes listed above.

There

are some cases where the cause is never determined.

It

is recommended as part of the daily routine to check the horse’s digital pulse

and hoof temperature. If either is

elevated now is the time to apply ice and start preventative treatment.

If

treated during this phase you may be able to prevent the laminitis. Treat with NSAID’s, lower blood pressure, and

laxatives if overeating of grain is suspected.

Research

has shown applying ice to the hooves during the developmental stage of

laminitis may prevent the onset of the acute stage. Dr. Chris Pollitt, researcher for the

University of Queensland, Australia, recommends the horse stand in ice 20

minutes twice a day with the time being extended to one to two hours depending

on the severity of the condition. During

research horses have stood in ice for 2 days straight with no detrimental

effects. (Click here for more information on

laminitis research.)

The

developmental stage may last 12 – 50 hours depending on the cause.

ACUTE: After the developmental stage the horse may

enter the acute stage. This is when the

first signs of hoof pain occur and many people first realize something is

wrong. Elevated hoof temperature and

bounding digital pulse may be apparent.

The coronary band may be swollen and distended. The horse may stand in the classical

laminitis stance of front legs extended trying to relieve pressure on the toes.

X-rays

of the hoof should be taken at this point. They will serve as a baseline for

future x-rays, show if the coffin bone has rotated from a previous laminitis

episode and allow a measurement be taken of the distance between the dorsal

hoof wall and the dorsal cortex of the distal phalanx. If the coffin bone shows severe rotation at

this early stage of laminitis the prognosis is poor.

Treatment

during the acute stage of laminitis is aimed at alleviating pain and minimizing

further damage to the hoof.

The

use of anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s) to make the horse more comfortable is

usually recommended. Phenylbutazone

(bute) appears to be the

most effective drug. Care must be taken

the horse is not made too comfortable and moves around excessively – causing

more damage to the hoof. The dose used

should take the edge off the pain and give him some relief.

The

attending veterinarian may recommend a vasodilator agent, but research has not

proven these drugs effective treatments in laminitis.

Most

veterinarians will recommend the horse be confined to a stall and the shoes be

pulled. These steps will lessen further

trauma to the already weakened laminae.

The

common mechanical treatment of the hoof is aimed at aiding break-over,

elevating the heel in order to decrease the force on the deep digital flexor

tendon and supporting the palmar/plantar (digital cushion) part of the

foot.

Dr.

Stephen O’Grady, farrier and veterinarian from the Northern Virginia Equine

Facility (http://www.equipodiatry.com),

recommends the following treatments be implemented.

To

remove the stresses placed on the laminae at break-over, a line is drawn across

the solar surface of the foot approximately ¾ inch dorsal to the apex of the

frog. The hoof wall and sole are beveled at a 90 degree angle dorsal to this

line using a rasp. This effectively

decreases the bending force or lever arm exerted on the dorsal laminae. It also

moves the break-over point back. Heel

elevation and support can be applied in one of three ways.

1. Sand is a readily available, inexpensive and

often-effective

form of foot support. It provides even support over the

entire

solar surface of the foot, and it allows the animal to angle

its

toes down into the sand, thus raising the heels and changing

the angle of the fetlock.

2. The use of 3-inch high-density industrial

Styrofoam has gained

popularity as a form of foot support. When applied to the

foot,

the weight of the horse crushes the Styrofoam, forming a

resilient mold in the bottom of the foot. It is easy to

apply, is

very forgiving, and it provides heel elevation and good

ground

support. Additional heel elevation can easily be fabricated.

Once the horse has crushed the

original piece of Styrofoam,

this piece is cut in half and the palmar half is retained

and

used as a heel insert. Another full sized piece of Styrofoam

is

applied underneath it.

3. The third method

utilizes a commercially available combination

of

two 5-degree wedge pads that are riveted together, along with

an

attached cuff so they can be taped to the foot.

These wedges

are combined with a resilient silastic material

placed

in the bottom of the foot for support.

This method is

used

on horses that have underrun heels, a broken hoof

-pastern axis or

radiographically show a negative heel angle

(the

solar margin of P3 is lower at the heels than at the toe on

the

lateral radiograph). To apply this

method, fill the bottom of

the

foot with dental impression material, hold the foot up until

the

impression material sets, place the foot in the wedges and

tape

in place. This method provides the best

heel elevation. All

of

the above support methods are easy to apply, provide firm,

but

forgiving support and allow easy removal to examine the

bottom

of the foot. They also provide uniform

support to the

frog,

sole and bars in the palmar/plantar two-thirds of the foot.

This is

accomplished without causing local ischemia and

pressure

necrosis which may occur if treatment is reliant on

frog

support alone.

The acute stage lasts until

the horse recovers or enters the chronic stage of laminitis.

CHRONIC: Not all horses will enter the chronic stage

of laminitis. Research has shown only 15

to 20 percent of the horses in the acute stage will progress to the chronic

stage – if proper treatment was implemented at the developmental and acute

stages.

The

chronic stage is when the laminae have died allowing the distal phalanx (also

known as the coffin bone, pedal bone or P3) to drop or rotate downwards. The signs usually exhibited by the horse are

persistent lameness, mechanical collapse of the foot, abscesses, and deformity

of the hoof wall. The horse is now

foundered (the coffin bone is sinking.)

The

treatment goal is to realign the displaced coffin bone; a goal usually

unattainable. Corrective trimming and

shoeing are the common methods used. Dr.

O’Grady has had much success with the use of glue-on shoes. (http://www.equipodiatry.com/chronlam.htm) More radical surgical treatments, such as

accessory ligament desmotomy or deep digital flexor tenotomy may be attempted.

Each case is different with different results, so the treatment of

choice may vary.

The chronic stage can last

indefinitely.