Equine Coat Color Genetics

Lesson Two

A Simple Approach

All horses fall into two (2) base

pigment color categories, either black or red. Some authorities include a 3rd

horse color at this point, which is bay.

However, since bay is a horse of which the base color is black, this

course will include bay, along with brown, a similar color result, under the

black base pigment color.

For each of these colors we will

discuss:

▪ How the genes that create it

work

▪ How to breed for the color

▪ How to recognize the coat color in foals

The Black Horse

The truly black horse is relatively

rare. To qualify visually, the horse must be completely black. It must have a black

muzzle and be black in the flank and around the muzzle and eyes.

However,

not all genetically black horses

The

color of some black horses fades in the summer. These horses appear to have a

rusty hue to their coats during the deep heat of summer, the result of sweat or

UV light on the hair coat. This visible

color variation has very little to do with a black horse's genetics, as far as

is known at this time.

How

the Gene Works

The

gene that creates the black pigment in a horse is called the

"extension" gene. The

abbreviation for is is universally accepted to be

E.

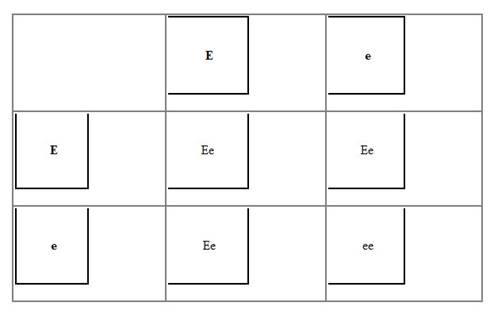

The extension gene (E)

works under the rules of simple dominance. Therefore it only takes one E

gene for a horse to be black.

Historically, horsemen thought that

the horse heterozygous for the black gene, the Ee

individual, had less depth to the color of their coat. It was also thought that

black horses that bleached-out in the summer were heterozygous blacks. This last

statement has never been proven.

If the black gene is present the

horse will be a black-based color. A

horse without the E gene (ee) will be not-black as

its base color. In horses, not-black (e)

is red.

How

to Breed for the Black Base Color

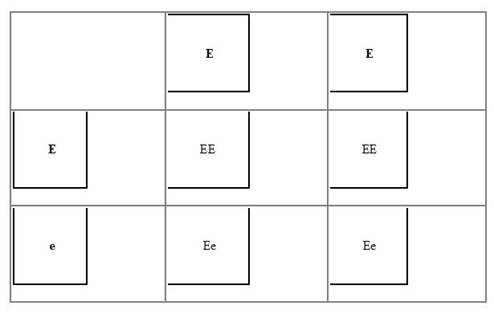

The

best way to produce black horses is to breed two homozygous black horses. Two

homozygous blacks (EE) will produce homozygous black foals

100% of the time. (See chart below.)

A

homozygous black (EE) bred to a heterozygous black (Ee)

will also produce 100% black foals because the homozygous black will pass a

black (E)

gene 100% of the time. (See chart below.)

This

is because it only takes one E gene to create the black-pigment-producing horse. 50% of

the foals will be homozygous for black and 50% of the foals will be

heterozygous for black, and all will produce black pigment where other

modifying genes allow for it.

However,

the best two heterozygous black horses can do is to produce 75%

black foals. The remaining 25% will always be chestnuts or sorrels.

What

Black Foals Look Like

Black

foals are usually not born black, but rather have a blue-gray hue to their

coat. They shed to black as weanlings or

yearlings.

The above picture is of a solid black miniature colt born

at Lucky C Acres Miniature horses. http://www.luckycacres.com

He is a good example of what a black horse will look like

when born.

When

a black foal will be born that looks truly black, like an adult horse, there

are often other genetic factors (like the gray gene) at work, and as an adult

the color will have changed.

The Chestnut or Sorrel Horse (Red)

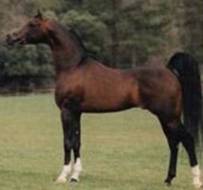

What is often referred to as a Sorrel

What is often

referred to as a Chestnut

The

horse with a reddish body and a reddish mane and tail, historically, has been

referred to as chestnut in Thoroughbreds and Arabians, and sorrel in stock and

draft horses. Genetically, they are the same (ee)

and in many instances it is very difficult to tell them apart by looking at

them.

Today

most breed associations distinguish between these two colors. Chestnut is

described as a darker red color. Sorrel is described as a lighter or brighter

red. Chestnuts or sorrels, whichever term you prefer, come in many shades, from

a very light sorrel to deep, rich brown-red.

In

this course, since all of these shades are created by the homozygous recessive

"e",

we will use the words chestnut and sorrel interchangeably, and call the base

color "red".

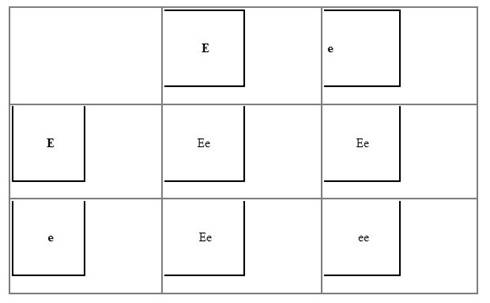

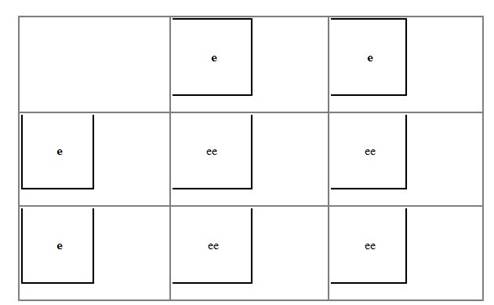

How the

Gene Works

The

chestnut or sorrel horse is created when the E gene is in the homozygous recessive form – ee

Because all red horses are Homozygous

for the recessive (ee), one truism in breeding horses is

red x red = red.

Chestnuts

can also be produced from the mating of two heterozygous blacks (Ee) about 25% of

the time.

Take

a few minutes and, using the

How to

Breed for the Color

If

chestnut/sorrel is your favorite color, you're in luck: it is the easiest to produce. Red parents

only produce red foals.

Chestnut/sorrel

(red) is a valuable color when trying to breed other colors based on the red

color.

Palominos,

strawberry roans, red roans and red duns are all built upon the basic red color.

It

is possible to test for the presence of the recessive e gene. While this has little value for breeders of red

horses, it does help breeders of black horses to determine whether their horses

are homozygous or heterozygous for the dominant E gene. This is referred to as a red

factor test. http://www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/horse/redfactr.htm

What

Red Foals Look Like

Foals

with the ee genotype are born some shade of red although

they may lighten or darken as they shed off their baby coats.

Red foals are usually born with very

light legs. This leads many folks to think that these foals have lots of white

on their legs. Most of the time, this isn’t so!

Although it is difficult to tell

until they shed off, the hoof does provide some insight. The hoof of newborn

red horses is grayish in color where the leg is going to shed off red. Where

the leg is going to shed off white the hoof will be cream or white. This does

create a change in the color of hoof, but may be difficult to see.

The Bay Horse

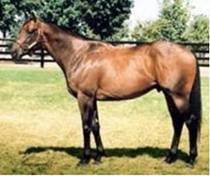

A

A

A

Bay

horses are the result of the Agouti gene on a black base horse. They have reddish bodies with black manes, tails,

and lower legs. The tips of the ears are black, as are their eyelashes. The

hoof of a bay horse is basically black. White leg markings change the black to

white in the area where the white color touches the coronet band.

Bay

horses range in color from dark blood bays to golden bays. This variation

occurs with all color categories and is referred to as shade.

There

are basically three recognized shades: dark, medium, and light. The genetics

behind these shade variations is unknown as of this writing.

How

the Bay (agouti) Gene Works

The

A

gene is a very "important" gene in coat color genetics, in terms of

its predominant distribution in the horse population. This gene limits its

expression to horses with a black base color. Its action is to lighten the body

color leaving the legs, mane and tips of the ears black, thus creating the

bay. Another way to describe it is that

it restricts the black color to the points of the horse (much like the coloring

of a Siamese cat).

The

predominance of the A gene is the reason for the small number of true black

horses. Although the black horse does not have the bay (agouti) gene, many red

horses do. Crossing chestnut/sorrel horses with the A gene on black horses does produce bays.

In

this example, a red mare carrying one A

gene has been bred to a homozygous black. This cross produces a 50% chance of a

bay and a 50% chance of a black.

(Note that the mare boxes include the

gene possibilities for both the E and A. When

first working with Equine genetics and the

How

to Breed for the Bay Color

The best odds of producing bay horses

come from the mating of two bay parents. And, of course, bays crossed on blacks

allow the A gene the opportunity to

act on the black base coat.

Bay is the base color for buckskins, Perlinos, bay roans and buckskin duns. Crossing any of

these colors provides the opportunity for a bay foal to occur, but it is not

the way to increase the odds that you will produce a bay.

What

the Foals look Like

Regardless

of the shade, bay foals are born with the tell-tale sign of black tips on their

ears. Most of them have black manes and tails. Their legs, however, may be

light, shedding to black later.

This bay colt is about 2 weeks of age. Notice the

characteristic grayish color to the lower legs.

This colt has one hind white sock.

Summary of bay: Bay horses are black-based horses which have

at least one (1) copy of the normal (A) agouti

gene. The bay agouti gene limits the

expression of the black coloration (E) to the “points”, mane/tail and lower

legs, of a horse. This leaves the body

color a reddish color. A bay horse does not need to carry a red gene to cause

the reddish body color. Agouti only affects the black coloration, so you can

have a chestnut/sorrel horse which carries agouti, but you cannot tell that by

its appearance.

The Other AGOUTI Gene: At

NOTE: in order to accommodate all

browsers, this gene will be noted as (At) for the remainder of this

course. However, the more correct way is

with the "t" as superscript (raised).

Brown (aka Seal Brown)

Brown (Seal Brown)

Horse -- black plus At

With

the ability to test for the agouti (bay or A) gene came the revelation that seal brown horses were not solid black horses with another gene

(usually believed to be the Pangare/Mealy gene) added

to cause the lighter shading. It is now known that Seal Brown is due to the At allele at the

agouti locus. This allele has been sequenced, named "brown", and

there is now a test for it.

http://www.petdnaservicesaz.com/equine-testing/

With

this fact comes a complication to the simple

The brown (At)

gene is recessive to regular bay (A), but dominant over non-agouti (a) (solid

black).

Other Modifiers

Additional

genes, called “Modifiers” work upon these two colors to produce the different

colors that appears on the body of horses.

As with any palette of colors, there

are factors which affect the hue, tone and shade of the true color. These modify,

but do not change, the genetic color makeup of horses, but they alter the

visual appearance of the colors.

They are:

Shade: This describes variations within a

basic color group resulting in light to dark body color variations. On a

chestnut/sorrel this modifier can result in colors from light and nearly yellow

to dark and almost purple, brown or nearly black. (Sometimes a "red"

horse can have a near-white, or "flaxen", mane & tail. The genetics behind this are unknown as of

this writing.)

Light chestnut/sorrel miniature horse

Dark Chestnut (Liver) stock type horse

Keep

in mind that both of the above horses are genetically red (ee).

If

you were to test these horses they would test identically for the red gene (ee).

Sooty: This refers to the presence of black

hairs among the otherwise-lighter body hairs. Most often this is noticeable

across the back, shoulder and croup, with the lower body appearing lighter.

Mealy (Pangare): This

modification causes pale red or yellowish areas on the lower belly, in the

flank area, behind the elbows, inside the legs, on the lower legs, on the

muzzle and over the eyes. This modification can occur on any base color and the

effect varies from minimal, very subtle and easily missed, to extensive,

causing dramatic paleness to the body. In the American Southwest, it is often

referred to as “muley", after a mule's

coloration.

This modification occurs on

chestnut/sorrel and bay horses.

On otherwise-black horses, this

appearance is actually caused by the At, or brown

gene, which was in the past usually called “seal brown”, after the coloration

of one species of seals.

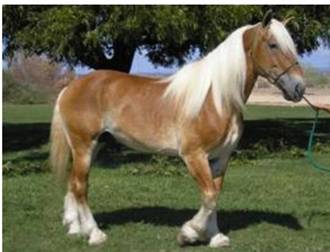

This is a Belgian (breed) sorrel /chestnut horse showing

mealy/pangare

This is a dark bay showing the Mealy/Pangare

The Ultimate Modifier – Gray

The “color” gray is a modifier, rather

than a color. All gray horses are born a ‘base/birth’ color, and they carry

those ‘base/birth’ genetics throughout their lives, and those genetics will

have an impact on what you get when breeding.

If

a horse carries the gray gene (G), then regardless of the color the horse is

born, the horse will turn gray. Gray is a progressive color

changer, in that as graying horses get older, most will eventually end up

white; the amount of time it takes to reach the white stage can vary from horse

to horse with some horses being white by five or six years of age and others do

not reach the “white” stage until they are in their teenage years. Some go on to develop "flea bites"

after turning white: specks of color that may or may not match their birth

color. This is called a

"flea-bitten gray".

The

photos below are of the same horse taken when the horse was a nursing foal, a

yearling and as a two year old. As you can see, this "gray horse" was

born chestnut/sorrel and started turning gray as a weanling/yearling. Its body

hair has lightened considerably with age, and will continue to lighten until

the horse is almost all white.

Photos are courtesy of “Cedar Ridge Ranch” www.grullablue.com

Gray

horses will continue to change color until they reach the “white” stage. Some

of the most famous gray horses are the Lipizzaners found at the Spanish Riding School of

Vienna. Lipizzaners

are born dark and turn white with age, with the occasional one staying dark,

indicating it did not receive the gray gene from either parent.

So,

to summarize lesson 2:

▪

All

horses come in one of two “base” colors; Black or Red.

▪

When

the black gene is present it will mask the presence of a red gene

▪

Bay agouti (A) limits black to the “points" of a horse

▪

Brown agouti (At) dilutes black on the muzzle, flanks, "armpits", and

some other areas of an otherwise black horse.

▪

Agouti

(A) or (At) only affects the black color

▪

Other

modifiers may be present which can affect the Shade, Smuttiness or Mealiness of the color of the horse. The latter two are often referred to as

"countershading".

▪

Gray,

while called a color, is actually a modifier that changes all colors from birth

or base color to gray.

▪

The

Punnett Square can be used to determine the possible

colors from a mating and their probability.

ADDITIONAL

http://www.horsecolors.us/darks/darks.htm