![Description: Description: Description: conf[1]](lesson_one_33_files/image002.jpg)

Conformation

and Selection for Performance

By Don Blazer, with Instructor Eleanor

Blazer

What

a horse does best is move.

His efficiency of movement is the

foundation of his survival, his evolution, his beauty and his grace.

By all accepted standards, what we say

is "good conformation" is said specifically as it relates to the

horse’s efficiency of movement.

If our desire is efficient movement,

then the ideal conformation is the form which best achieves efficient movement.

And by its very nature, it is also the form which most assures, BUT DOES NOT

GUARANTEE, continuing soundness.

But efficiency of movement is not

always what we want.

Various breeds accentuate certain

conformational traits which affect movement, and particular performance

disciplines demand distinctive variations of movement. So the desire for

efficiency of movement is replaced by another desire. The new movement desired

always subjugates efficiency. And over a period of time the various desired

movements result in conformational changes. The changes in themselves are not

necessarily right or wrong; they are simply choices. But all choices which

limit natural efficiency of movement come with consequences.

Click on the following link to see a

“quick conformation overview”. This is a

standard conformation report that does not relate form to specific function, a task you will be

asked to do at the end of this lesson.

https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/g2837

Understanding a horse’s conformation,

and the deviations from the established standard, allows you to recognize how

and why a particular horse moves as he does. And with that understanding you

can choose the performance work most suitable for that individual.

But before we begin our observation of

specific conformation traits and their affect on performance, I want to review

some basics of horse identification and reference. Click on the link to view the

information. (If you have a slow server

– be patient – the graphics may take some time to download.)

There are two ways to judge a horse’s

conformation.

One: determine the correctness of the

form as it relates to efficiency of movement. (This is supposedly how halter

horses are judged--form as it meets the breed standards. Halter horses of any

breed seldom reflect efficiency of movement, instead portraying the

"beauty" of the current fad, which is correct if meeting the

standards of a new desire.)

Two:

determine the strengths and weaknesses of a particular conformation as it

relates to the performance desired. (Selective breeding has been successful in

producing horses with both conformation and talent for specific exercises.

Knowing what performance you want from a horse allows you the opportunity to

select by breeding, the natural desire to work, and by conformation, the

natural ability to work.)

Always keep in mind that a horse’s

action is initiated in the hindquarters. The hindquarters is

the power plant of the horse, the driving force. The forehand catches,

rebalances and stabilizes the horse. The conformation you are seeing (forehand,

hindquarters, overall) should be evaluated either in relationship to how well

it can function in performing the desired movement, or for its contribution to

efficiency of movement.

View a horse’s conformation from three

positions "directly in front of the horse, at the side of the horse and

directly behind the horse. Looking at the horse head-on allows you to see the

width of the forehead, the chest and the alignment of the front legs. Looking

at the horse from the side allows you to view the set of the head and neck, the

top line, the underline and the positioning and angle of the legs. Standing

directly behind the horse you can see alignment of the hind legs, the level of

the hips and the straightness of the spine. (To fully see the spine, it may be

necessary to stand on a platform to elevate your view.)

Conformational Balance

Balance is the overall symmetry of an animal and is

one of the most important of the evaluation criteria. Balance is evaluated by

viewing the profile of the animal. When viewing the horse, his body should

appear symmetrical with all of his parts blending smoothly together.

The length of a horse's head is a good guide to his

overall balance. If a horse is

"well balanced" his head will be approximately the same length as the

distance from the point of the hock to the ground, or the chestnut on the front

leg to the front foot, or the elbow to the fetlock joint, or the depth of his

body at the girth, or the point of the stifle to the point of the buttock, or

the point of the stifle to the point of the hip. Click

here to see a picture.

There are

several standard ways to evaluate balance and these are illustrated in the

following diagrams.

![Description: Description: Description: conf[1]](lesson_one_33_files/image002.jpg)

A well-balanced horse can be divided into two equal halves. Although not the most common method, many beginners can visualize "halves" better than thirds. A horse should not appear more massive in the forehand than in the hindquarters (or vice versa). Rather a horse with a well-developed forehand should have well-developed hindquarters to match.

![Description: Description: Description: conf[1]](lesson_one_33_files/image004.jpg)

This illustration depicts the more common and more correct way to evaluate balance.

A horse that is balanced should have lengths of

head, top line and hip that are nearly equal. Similarly, a balanced horse can

have his body divided such that the lengths from the point of the shoulder to

the barrel (a), from the barrel to the point of the croup (b), and from the

croup to the point of the buttocks (c), are equal.

![Description: Description: Description: conf[1]](lesson_one_33_files/image006.jpg)

In addition to balance from head to tail, a well-balanced horse should have a similar distance in the girth (a) as from the underline to the ground (b). Horses which appear shallow-hearted, or to have extremely long legs are not considered well balanced.

![Description: Description: Description: conf[1]](lesson_one_33_files/image007.jpg)

The final consideration in evaluating balance is

determining how level the horse is over his top line. A balanced horse is similar in height from

the ground to the withers (a) as from the ground to the croup (b). A horse that is higher in the forehand or

higher in the croup is not well-balanced.

Generally, a horse with a long-sloping shoulder will have a short top line. A short top line is desirable because shortness denotes strength of top, and a top line that will withstand the stresses of riding. Note the difference between horses with strong and weak top lines.

![Description: Description: Description: conf[1]](lesson_one_33_files/image009.jpg)

When viewing a horse for strength or correctness of the top line, the top line should appear relatively short in comparison with the animals underline. Horses long in the loin will appear to have top lines and underlines of similar length.

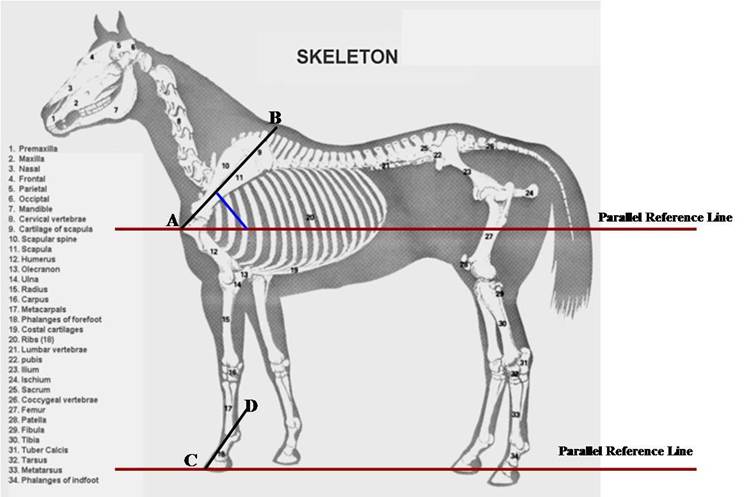

ANGLES

Skeletal angles will dictate if a horse will be able to stand up to the stress of performing. The angles of will affect the fluidity of movement and his soundness.

*

A to B is the slope of the shoulder.

(Point of shoulder to the highest point of the withers.)

The

blue line is the angle of the shoulder—approximately 45 degrees in the

“perfect” horse.

*

C to D is the slope of the pastern. Ideally it will be close to the same angle

as the slope of the shoulder.

The skeleton shown is drawn to be a perfectly balanced horse with maximum efficiency of movement. Seldom do we see such a horse.

To aid you with visualizing degrees, here is a handy scale.

Students will need a protractor for completing assignments. Order from Amazon or get one at your local store.

The angle of the shoulder will determine the length of stride. An upright shoulder will produce short choppy strides; a long, laid back shoulder will allow for more range of motion (speed, flexibility, extension).

The next diagram shows the angle between the shoulder blade and the humerus.

*

A to B is the slope of the shoulder.

(Point of shoulder to the highest point of the withers.)

*

A to C is the angle of the humerus from the point of the shoulder to the elbow.

The

“perfect” horse will have about an 85 degree angle. (Notice how close the angle is to 90 degrees

– refer to the degree scale.)

If the angle formed by the shoulder and humerous is too acute (closed together) the front legs will be set back under the body. It will appear his chest is sticking out (pigeon breasted). The resulting gait will be uncoordinated and lack length. If you want a jumper avoid a horse with an acute angle. The most talented jumpers will have a shoulder/humerous angle of 100 -110 degrees.

The next diagram shows the desired hindquarter angles. These measurements are taken from the point of the hip, to the point of the buttock, to the stifle and back up to the point of the hip. It should form an equilateral triangle.

FEET

If I am looking at a horse for possible

purchase, I will stand in front of the horse and look at the coronet bands of

both his front and hind feet. I want to see an even coronet band, symmetrical

with the opposite one. The coronet band should flow across the front of the

foot and should not have dips or upward variations. The hair line should move

evenly around toward the heel and should not sink down toward the ground. Any

deviation in the hair line at the coronet band tells you there is something

going on of concern.

Keeping the coronet band as the main

focus, I can view the entire hoof. I look for flares, differences in the angle

of the medial and lateral hoof wall, pulled in heels and hoof wall damage.

Moving to the side of the horse I look

for dorsal/palmar (front to rear) balance. Determine if the horse has a broken

forward or broken backward hoof/pastern axis. Carefully analyze the angle of

the hoof wall horn, noting any tendency toward under-run heels.

I then pick up each foot and look at the

medial/lateral balance, the condition of the frog, the medial/lateral heel

lengths, the position of the bulbs of the heel, and the width of the heel.

A horse with small feet can do just

about anything, but his soundness will be questionable, especially if he is

asked to work in high impact events.

Flat footed horses should be worked only

on soft footing.

Mule feet are narrow with steep walls. A

horse with mule feet should be worked only on soft footing.

Coon footed means the horse has a very

upright foot, while the pastern slopes radically toward the hindquarters.

Club feet are defined as a foot with

high heels and a front face which exceeds 60 degrees. Club feet can be genetic,

caused by the horse having one leg shorter than the other, or faulty

nutritional practices with young horses.

Contracted heels and small frog are

common results of poor shoeing practices. Horse with such problems should be

used only in non-concussion events.

Narrow hoof walls predispose the horse

to sore feet and are often associated with flat feet.

Without a foot, the rest of the horse’s

conformation matters little. If the horse has too many obvious foot problems, I

don’t have an interest in purchasing him. While most foot problems are the result

of poor care and/or poor shoeing, many will be associated with conformational

faults.

If I have been asked to evaluate the

horse, I simply note my observations of the hoofs and move on.

HEAD

Return to a position in front of

the horse and study the horse’s head.

The horse's neck should be 1.5 times as long as the head, or a bit

longer.

Now examine the horse's nostril. I want to see a large nostril, capable of

opening wide to allow maximum air flow. A great air supply is extremely

important to any horse which will be used in activities requiring speed and

stamina. (Racing, cutting, jumping, eventing.)

The more air a horse gets into his

lungs, the more oxygen the blood carries to the muscles, having a direct effect

on the horse’s ability to perform.

A horse with small nostrils should be

considered for pleasure riding or trail.

It is best if the horse’s face is

neither dished nor bulged out. A smooth, straight line from a point between the

ears down the nose to the nostril allows air flow. A dished face is a major

restriction to air flow and severely limits the horse’s ability to perform with

speed or stamina. A bulging face line (Roman nose) interferes with the horse’s

ability to see clearly and is usually associated with horses of poor

temperament, willfulness or spookiness.

A large, soft eye set to the side of the

head generally allows the horse to see well, and is associated with a horse of

kind temperament. Small eyes, often called pig eyes, restrict a horse’s vision.

The horse has both monocular and binocular vision. He can look at two different

things at the same time, or he can use both eyes to concentrate on a single

point, so what he sees can be quite distracting to him. In addition, the retina

of the eye doesn’t form a perfect arc, so the horse must frequently shift his

head position to bring particular observations into focus.

It is not advisable to have the eyes set

too far to the side of the head, as this causes the horse even more trouble

bringing things into focus. It is also much more difficult for the horse with

wide-set eyes to focus both eyes on a single object, which in turn limits his

ability to concentrate.

A horse with a well defined jaw line

usually has a relatively wide jaw, which is an asset. Make a fist and place it

between the horse’s jaw bones at the throatlatch. A horse of one year or older

will have what is considered a wide jaw if you can slide four knuckles of your

fist between the jaw bones. This width allows for good air flow.

With width between the jaw bones, the

throatlatch will be clean and well defined. A well defined throatlatch is

important since everything essential to the horse’s performance--blood, nerve

impulses from the brain, air--travels through this area.

Horses which are narrow between the jaw

bones should be directed toward performances not associated with speed or

endurance.

NECK

The neck is measured from the poll to

the withers and should be about one-third the length of the horse’s body

measuring from the tip of the nose to the buttock. The neck should be at least 1.5 times longer

than the head, and the same length as the horse's front leg (elbow to ground).

The neck should be set on the horse’s

chest neither too high, nor too low, but aligned for forward movement.

A short neck will cause the horse’s

stride to be shorter, but the shorter neck will allow for quick air flow to the

lungs. A short neck is not considered

advantageous for a jumper or for a horse expected to work with speed for long

distances. However, a horse with a short neck gets plenty of air to sprint.

A long neck causes the horse to be heavy

on the forehand, but is acceptable in jumpers and horses working in straight

lines.

An upside down, or ewe neck relates to

high head carriage and compromises all performances. A horse with the upside

down neck is often called a "stargazer", and is often

under-conditioned because it is difficult for him to engage his hindquarters.

Ewe necked horses are frequently underweight and many have a bulging underline.

The horse with a large crest or

"crest fallen" neck is usually the product of obesity, which, of

course, can be corrected.

A bull neck is a heavy neck with a short

upper curve. Horses with this conformation generally work best in harness.

Horses with a swan neck--almost an

"S" like curve--never work well on the bit and often tuck their chins

to their chest. This neck generally has a long dip just in front of the withers.

A naturally arched, well-defined neck is

suitable for any type of work.

THE BODY/WITHERS

When examining the horse’s body, begin

with the withers. The withers are formed by the coming together of the left and

right scapula, which don’t actually touch, but are held in place by muscles.

If the withers are rounded, flat and

with little definition, they are called "mutton withers." Mutton

withers affect all physical action and allow no free flow of movement. Saddles

slip easily on mutton withered horses.

High withered horses are hard to fit

with a saddle, but can generally perform any kind of work.

THE BACK

The horse’s back lies behind the withers

and to the loin, which is defined as the last rib to the point of the hip. The

loin is considered to be long if it is more than a hand’s length.

The back is generally a bit longer than

30 per cent of the horse's body length.

(the forehand…point of shoulder to back of

withers…should be 30 per cent of body length, the hindquarters…point of hip to

point of buttocks…should be 30 per cent.

Therefore, the back, depending on the length of the loin, will be a bit

more than 30 per cent.)

A hollow back looks concave and can be

rider induced due to a lack of drive from the hindquarters. Riding with

incorrect contact, a pull instead of a push, creates the low back and a strung

out horse. This condition is often seen in horses used for distance trail

riding.

Short backed horses have limits to their

lateral flexion, and therefore generally lack suppleness.

A roach back--the spine raises in the

loin area--is often associated with stiffness in the back. Roach backed horses

cannot use their loin properly and so they are limited in quick lateral

movements.

Long backed horses generally have a weak

loin area. The weakness here precludes them from "folding" (drawing

their hind legs forward under them) quickly, so these horses lack both speed

and power.

A horse is said to have "rough

coupling" if he has any kind of a depression in his back just in front of

the croup. Rough coupling can be compensated for by being sure the horse is

very well conditioned.

THE CHEST

A horse with a wide chest can do just

about anything, but the width will often adversely affect the horse’s length of

stride and speed. Look for a horse with a chest proportional to his overall

look. If you immediately notice the horse has a wide chest, he probably has a

little too wide a chest.

RIBS

Standing in front and just a little to

one side of the horse, you should see "well-sprung" ribs, meaning the

ribs are prominent at the heart girth area. Well sprung ribs taper in as they

approach the horse’s flank.

Barrel ribs are prominent all the way to

the flank. The horse has a body "like a barrel." This width all the

way to the flank generally accounts for an uncomfortable ride, because the

horse cannot easily bring his hind feet well forward and under his body.

Pear shaped ribs are narrow at the heart

girth and widen toward the flank. A horse with pear shaped ribs should be used

on level terrain and cannot be expected to do a lot of work. As the barrel

ribbed horse, he cannot easily bring his hind legs forward.

FRONT LEGS

Looking at the front legs from the

front, you should see the form of the bone entering the joints in the center.

A horse with a base narrow stance cannot

be expected to perform well in speed events or events which require athletic

agility.

Base wide horses are best suited for

easy pleasure riding.

Horses which toe-out can be used for

high impact events, while horses which toe-in should be used only in low impact

activities.

Move to the horse’s side to evaluate the

horse’s shoulder. An upright shoulder indicates the horse can work in sprint

activities. The horse’s speed lies in his ability to gather and get into the

next stride, not on the length of the stride. In other words, the more strides

within a particular distance, the more speed. A horse increases speed by

driving off the ground. His speed slows as he travels through the air.

If the horse has a sloping shoulder, his

withers will be well behind his elbow. Horses with this conformation are well

suited for jumping, dressage and driving.

A long arm produces speed, but is also

excellent for the dressage horse.

A short arm "from the point of the

shoulder to the elbow" will create an angle of less than 90 degrees.

A long forearm favors speed and jumping

ability. The horse with a short cannon will generally have speed, agility and foreleg soundness.

From the side you can determine whether

or not the horse is over at the knee or back at the knee. Back at the knee

conformation is frequently associated with unsoundness, but is also the desired

conformation for the modern western pleasure horse as he will move slowly with

flat knees and little reach.

Over at the knee horses are not pleasing

to look at, but many have speed and seem to remain sound.

Look at the horse from the front to see

if the horse has bench or offset knees. A horse is said to be bench kneed when

the forearm enters the knee to the left or right of where the cannon bone exits

the knee, making the forearm the back of the bench, the knee the bench seat and

the cannon the bench legs.

An offset knee has both the forearm and

the cannon entering and exiting the knee either on the medial or lateral side.

The fetlock joint should be clean and

well defined.

A horse with long pastern provides a

smooth ride and makes a nice pleasure horse or dressage horse.

Short pasterns contribute to a harder

ride, but also aid a horse’s speed.

A.

Straight legs, good front

B.

Splay-footed

C.

Pigeon-toed

D.

Knock-kneed, narrow front, base wide

E.

Base-narrow

F.

Bow-kneed

HINDQUARTERS

Stand at the side of the horse to begin

your evaluation of his hindquarters.

The perfect length of the hindquarters

is 30 per cent of the total body length and is measured from the point of the

hip to the point of the buttocks.

A short hindquarters

“less than 30 per cent of body length” is associated with a horse which lacks

speed and power. Remember, all action initiates in the hindquarters.

STIFLE AND HOCK

The

stifle joint should be about the same height as the elbow of the front leg and

directly under the hip, creating a low joint for better leverage for the

muscles of the hindquarters. If the

stifle is low, the muscles along the back of the hindquarters can be longer and

stronger continuing down toward the gaskin.

(This is just the opposite of what we see in today's halter

horses.) When viewed from the rear, the

stifle should be slightly wider than the hip.

The

hock is complex and worked harder than any other joint, so it must be well

proportioned and strong. A large,

well-formed hock provides power for motion and greater area for absorbing

concussion.

The

point of the hock should be level with the chestnut on the horse's front leg

and directly below the point of the buttocks with a slightly turned in angle

for best leverage and strength.

Finally,

the distance from the stifle to the point of the hock should be equal to the

distance from the point of the hock straight down to the ground.

CROUP

A flat or horizontal croup is associated

with a flat pelvis. The topline of the horse continues all the way to the dock

of the tail. Horses with flat croups “which are quite common” have a flowing

stride at the trot. They are especially good at distance trail riding, and

driving in harness.

A steep rump is called a

"goose" rump and is not particularly common. Horses with a goose rump

are best suited for slower types of work, such as pleasure or trail riding. The

steep slant of the pelvis shortens the backward swing of the leg.

Narrow hips limit the amount of muscle

the horse can carry, thereby limiting the amount of muscle power possible.

A "knocked down" hip is when

one hip bone is lower than the other. The condition is fairly common. When

examining the horse from the rear, be sure to watch carefully as he is walked

away from you.

A long hip is easily recognized when the

stifle joint sits at or below the sheath line on a male horse. Low stifles are

particular good for horses which are intended for eventing

or show jumping.

A short hip creates a high stifle joint.

Horses with high stifles are best suited to draft work.

A short gaskin is associated with high

hocks, which generally means the horse will have inefficient movement, taking

an extra long stride.

High hocks make a horse suitable for

trail, pleasure riding, or driving.

A long gaskin is associated with low

hocks which often puts the horse in a camped-out position. Horses which are

camped-out behind lack power and smoothness. He can best be used as a trail

horse or pleasure horse.

The gaskin length is best when it sets

the hocks at the same level as the horse’s knees, for the horse will usually

have both power and speed. When evaluating the potential of a horse which will be

asked to work with speed and agility, look for hocks which are at the same

level as the knees.

Sickle-hocked horses should not be

considered for speed events, while post-legged horses--very straight hind

legs--are particularly good at speed events, but little else.

A horse is said to be cow-hocked if when

viewed from behind the cannon bone and the fetlock joint are well to the

outside of the hocks.

If conformation is demanded in

relationship to efficiency of movement, a horse will tend toward a natural, but

moderate, cow-hocked stance. The horse’s toes should point outward, and he

should NOT stand square behind as virtually all conformational standards

require.

When a horse increases his speed, the

hips and the hocks rotate outward, and the hoof rotates inward. A horse which

stands square behind naturally--and they are very, very rare--will strike his

front legs with his rear feet when he moves with speed.

Never allow a farrier to trim a horse’s

hind feet high on the inside to make the horse stand square behind.

Do not endorse breed association rules

of showing which allow a handler to "pull" the horse’s hocks out,

twisting the foot into a straight forward position. That is not the horse’s

conformation and it is ignoring the truth if it judged that way.

A. Correct skeletal structure.

B.

Correct leg set.

C.

Sickle-hocked or too much set.

D.

Post-legged or too straight, “coon-footed”.

E.

Camped-under or stands under.

F.

Defects of this magnitude should not be propagated.

BALANCE

A horse is said to be balanced when his

withers and croup are level. A balanced horse is generally capable of working

any type of event.

Light boned horses should work low

impact and low speed events, while course boned horses are more suitable to

high impact events such as eventing.

LEG JOINTS

The joints of both the hind and fore

legs should be clean and dry in appearance. Any puffiness or signs of fluid

indicate joint damage and eventual problems.

The pasterns, hind and fore, should be

tight and dry.

FINAL ANALYSIS

View the horse from the front, the side

and from behind, looking at the entire horse as a single object. Do you like

what you see? Is he smooth in overall appearance, or does some angle or

roughness jump out at you?

As you decide on the importance of each

conformation point you have viewed, evaluate you observations in relationship

to efficiency of movement, or to the work you want the horse to do.

Every horse can do everything and

anything to some degree. But mediocrity in performance seldom pleases the

horseman. So it is the responsibility of the horseman to understand how the

form affects function, and to select the correct conformation for the work to

be done.

It is a bad horseman who demands a horse

work at an event for which he is not properly conformed.

Conformation is visible, but the thing

which makes performance champions cannot be seen. A horse’s heart to compete and win cannot be seen, but accounts for

‘super efforts’. Still, the horse moves

to into the winner’s circle on his physical conformation.

Quizzes are best viewed using Chrome or

Firefox.

Assignment:

1. Make a video of you going over the parts of the

horse. Please do not use a

“cheat-sheet”. Practice before you submit the video and can do them from

memory. Feel free to send more than one

video in order to cover all the parts.

The preferred method of sending the video/s is to load to YouTube and

send me the link. Be sure the setting is for “public” and not “private” at

YouTube. elblazer@horsecoursesonline.com

2. Please write a detailed

conformation evaluation of the horse pictured. Check essay for proper spelling

and format. Send your report to elblazer@horsecoursesonline.com

Click

here for a conformation evaluation guide developed by Melinda Hertel, a

professional certification student from Gilbert, Arizona. This chart will help you evaluate the

pictured horse and other horses.

You will not be

able to get his actual measurements, but you can make pretty accurate

proportional approximations. Please

include angles, such as hoof, pastern, shoulder and hip; evaluate legs, joints

and feet for correctness.

Save this report, you will need it at the end of

lesson two.

The horse

pictured is 4 years old, 16.1 hands and approximately 1200 pounds.

Click here to

view picture one – The Complete Horse, Left Side

Click here to

view picture two – The Complete Horse, Right Side

Click here

to view picture three – The Legs

Click here

to view picture four – The Front Legs and Chest

Click here

to view picture five – The Head

Click here to view picture six –

The Hindquarters