RIDE COMPETITIVE TRAIL TO

By Vickie Zapel, PrI

Lesson

Six

My

Horse will go Anywhere, Anytime, Through Anything

CROSSING OBSTACLES WORKS BEST IF THE HORSE THINKS IT IS “HIS” IDEA

When we lead or ride our horse to a

water obstacle, we want to have a positive experience which builds confidence

and trust in our partnership with our horse.

It is best if crossing water is the

horse’s own idea. It will be his idea

and he will be agreeable, if you’ve spent the necessary time and effort

required in Lesson Five. If your horse

is still not keen on water obstacles, keep working on desensitizing him with

the program previously outlined.

The time it takes to master water

obstacles will vary depending on your skill level, how many times a week you

can work at it and your horse’s past experiences. Do not be easily dissuaded; the system will

work and you can be safe implementing it.

If your horse is now doing very

well on the lunge line, whip/stick, and in-hand training for crossing water and

mud, you are definitely ready to start riding the same exercise.

If while riding, your horse is

objecting, and those objections cannot be overcome by simple leg pressure and a

verbal “cluck”, stop riding and go back to more in-hand work. You do not want any kind of a battle about

water. You need to repeat your water obstacle ground work.

You will always want to practice

fairness with your horse. You are the

parent and he is the little kid in a really big body. Encouragements are fine, but never rush an unsure horse. In any situation where the horse is objecting, patience is always your best virtue as

long as the horse is still trying. Work

obstacles where you can build confidence and security in basic training

maneuvers. However, it can be a fine

line to differentiate, if your horse has flat out made up his mind he is not

going to have a meeting of the minds with you; then you are in a situation

where you’ll have to change his mind.

If you are not comfortable or

capable of doing this from the saddle, immediately go back to your basic

training of working in-hand on a water obstacle that you know you can manage

with the horse. Increase the degree of

difficulty of the in-hand work, until you have a built a pliable, confident,

obedient partner.

When presenting an obstacle, let

the horse put his head down and look; don’t ask him to move forward if he is

not first in position to “look” where you want him to go. Slow movement on the part of the horse slows

down his thought process; given time to think about the obstacle makes the

horse surer of himself.

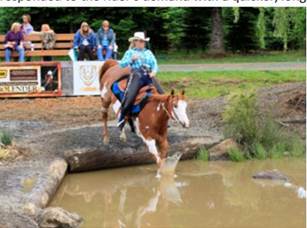

The following photos show what

happens when the horse is not allowed enough time to think.

Everything

about the approach to the obstacle looks good.

1.

The horse does not appear resistant.

- His

front feet are placed right up to the edge of the entrance log.

- His body is straight.

4.

He

is intent and seriously observant.

5. The rider is balanced and has

given the horse extra rein length so he can put his head down.

6. The rider is not leaning downhill

and she is looking where she wants to go.

7.

The horse makes his commitment to the

obstacle and all remains well, except for the distance of the step by the front

feet. The rider wanted to move on before

the horse was ready, so instead of an easy slow step, which the horse was

positioned to make, the horse responded to the rider’s demand with a quicker,

longer step.

8. The result is more of a faltering

jump than a “step down”.

9. As the horse’s left front foot

lands, the right front follows in an even further forward placement. The rider

had to lean backward in a hurry to compensate for the horse’s surge

forward. It looks ugly and it feels

ugly.

To better understand the approach

to this water obstacle the pattern required trotting to the very edge and then

stepping off into the water. During the

Judge’s walk-through, the host of this event made a point of stipulating that

he did not want to see any hesitation at all, at the log entrance step

off. Competitors were explicitly

instructed to go from the trot gait to a walking step off immediately into the

water. This horse at his skill level

needed just a second to “think” before stepping off, as he was not accustom to

trotting right to the edge of a drop off step down.

It

was the rider’s mistake in judgment—rushing the horse-- that made the step-off

ugly.

You

are always better off to build your horse’s confidence than trying to earn

“bonus” points in the competition.

Always be advised that you ride to the level of your horse…do not push

him beyond what he is comfortable or capable of doing.

Give

him to time to think about an obstacle if he needs that time.

We

all make judgment mistakes; especially during a competition. It is not the end of the world; it is just a

learning process. Frequently, you will

find you will learn more as a team by riding a pattern with obstacles you have

never experienced. If you make a mistake

in judgment, learn from it; shame on you, if you make that same mistake twice.

THE

HORSE’S FOUR FEET

Learn

to trust in your horse’s four feet, they have been connected to the rest of his

body for a very long time. Even when he

doesn’t act like it, the horse does know where his four feet are. Sometimes, he just doesn’t know where to

place his feet and needs a reminder to pay attention to them.

Remember

we studied keeping the horse’s spine straight in past lesson material. You know that it can be extremely difficult

to keep the horse’s spine (poll, neck, shoulders, rib cage and hips) straight,

if the rider is not balanced.

There

is no way a rider can be absolutely balanced leaning forward at a 40 degree

angle, attempting to balance on the inside of his thighs, because his behind is

up out of the saddle, while the rider is bent over the horse’s neck with his

head tilted down, as demonstrated below.

Photo

courtesy of

The

above photo shows a respectable working team.

This horse and gentleman appear to be in unison. The horse is willing and paying attention to

where he needs to go.

The

rider’s heels are down and he has optimal leg contact with the horse’s sides,

but the rider is leaning forward with his shoulders, which puts him out of

balance; especially if he needs to recover should the horse decides to spook or

jump. It is a safer position (balanced)

for the rider to keep his shoulders over his hips, which keeps his seat in full

contact with his saddle, making it easier and quicker to apply necessary hand

or leg cues.

Note:

to maintain his forward riding position the rider actually has his knuckles

resting on both sides of the horse’s neck.

If he needed to make a quick rein cue, his balance and the horse’s

balance are going to be lost. The rider

has taken his position because he is trying to look at the downhill entrance

into the water pond. It is only the

horse that needs to look at where his feet are in this type of circumstance.

(The rules of many competitions prohibit touching the horse’s neck at any

time.)

The

rider does NOT need to see where his

horse’s feet are; his horse can see the ground.

The horse has his head down and is looking where he is going; he knows

where his feet are. Allowing the horse

to work the obstacles is how you score points.

Not

to mention that a horse already packs two thirds of its body weight on the

front end, that is increased with the rider trying to balance forward and over

the front of the horse’s shoulders, making it even more difficult for the horse

to move forward, pick up his feet over poles, rocks or logs, or pull his feet

out of deep mud, stay balanced and maintain his own body position.

So,

you would ask, “Just how are you supposed to guide the horse where you want it

to go”? The

answer is: by LOOKING WHERE YOU WANT TO

END UP.

On a

long obstacle you might start by looking at the center. As you travel toward the center, change your

focus to just past the end of the obstacle, right to where you want to exit.

Look

at, or past the end of the obstacle as you approach the end, but do not look

down. Look forward; concentrate on

something directly in front of you. Look

where you need to go.

Actually,

the judge should be able to tell where the rider intends to go, by following

the rider’s path of vision.

LOWER

You’ll

need to develop a cue to tell your horse to lower his head on command.

Generally,

a slight upward and forward movement of your rein hand in combination with a

gentle squeeze of your legs or a modest, simultaneous “bumping with your legs” makes

a good “lower head” cue. If done

correctly, it should be barely visible to the judge.

Practice

the “lower your head” cue in front of any obstacle. Begin to work the obstacle only after the

horse has put his head down to investigate.

Elevating

your hand along with the leg squeeze or bump is very similar to the way many

trainers cue for the horse to set his head.

However, by also moving your hand forward at the same time you give the

horse additional rein length allowing him to put his head down far enough to

see where he is going to put his feet.

It

won’t take long for your horse to recognize the cue.

When

the horse puts his head down, your rein will be lengthened and close to the

ground. Be careful not to give the horse

so much rein that he could step on it.

This can easily happen on very steep, downhill obstacles.

Don’t

let your horse get into the habit of touching the log, teeter-totter or

obstacle in front of him. He can look at

and smell it without touching it, but unless he is very young, very

inexperienced or very insecure, he does not need to “touch” the obstacle with

his nose. Most judges will consider this

a sign of insecurity in the horse and you can lose a point for it.

In the photo below, the horse is

touching the obstacle and the rider is not aware the horse has made

“contact.” A well-schooled horse will

have worked bridges and teeter-totters so many times that it should never be

necessary for him to “touch” the obstacle.

When a horse “touches” an obstacle with his nose, it usually means he

has “stopped” moving forward; therefore the pattern flow was interrupted

unnecessarily, which will also cause lower scores.

RE-INVENTED

REFUSALS

When first

learning to work obstacles, horses can invent and re-invent ways to

refuse. Watch this horse.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DgAX98MccB0&feature=c4-overview&list=UUM8nQJSFFUQCK8yRRGw0xCg

Did you note the

repeated sideways and backward movements?

The horse made several attempts at various movements, but didn’t want to

move forward. In the horse’s mind, if

one type of refusal didn’t work, surely a different refusal attempt will. The refusal attempt may be minor or full

blown.

However,

once his rider had the horse really “look” at the obstacle and focus on where

he needed to put his feet, the horse responded by moving forward.

Make

sure your horse is “looking” where he needs to go before you ask him to move

forward. He needs to see the obstacle

before he can be comfortable and confident.

The

horse in the video was very inexperienced, so we can excuse the evasion. But in excusing the evasion, we must create a

new schooling plan to show the horse what we want.

The

rider/trainer could ride a loop around the trench three or four times; working

their way closer and closer to the entrance and then ask the horse to walk to

the center and enter.

When

you are approaching an obstacle, be prepared to ask the horse to put his head

down and look at the obstacle. As you

ask him to lower his head, you must also be prepared for the novice horse to

make an evasive move. If he attempts to

move to the left, block that movement with your left leg and left rein by

pushing him deliberately back toward the center. If he starts to move back to the right too

quickly, you’ll have to shift your cues to the right side of the horse, and

block the movement with your right leg and right rein so he does not continue

to turn completely around. If he decides

to back up, strongly ride him forward, even if you cannot go forward directly

or straight into the center of the entrance, still ride purposefully forward.

Trying

to turn or back away from an obstacle is usually the horse’s first choice when

refusing. Relax and think how you can

get the horse to think it is his idea to work the obstacle. Your first step may be to sit there for a few

minutes and just let the horse have time to look at the obstacle, think about

and decide to approach on his own.

Never let the horse turn completely

around. If he starts to make a 360 turn

to the left, for example, use your left leg to hold the ribcage and the right

rein to pull his nose back to the right.

Be very positive in your correction.

When you are facing the center of the obstacle again, ask the horse to

put his head down and look. As long as

he studies the path you want him to take you are making progress. It is any

evasion to standing and inspecting the obstacle that is not allowed.

THE RIDER’S

There are two types of “re-check”:

mental and physical. Try to make your “re-checks”

simultaneous.

For the physical re-check, start

with your heels. Are your heels

down? Are you centered in your saddle

and not leaning to one side? Are your

shoulders up and square, is your chest open.

Are you looking where you want to go? Are you breathing? Is your rein hand forward with enough rein

length that you are not interfering with your horse’s forward movement? Have

you properly given your horse his cue to put his head down and focus on his task?

Have you aligned yourself to be balanced?

Many obstacles present a moment of

opportunity to make your re-check; for example, while standing in a holding

position between judges’ quadrants or sectors.

How about while you are counting off five seconds as your pattern calls

for a hold on a bridge? Or the quiet moment before you side pass away from the

gate. Slow your own thought process

whenever you can.

During your “re-check”, take a

breath. Your involuntary muscles won’t

let you turn blue, but they cannot stop you from holding your breath. We all tend to hold our breath when under

stress or concentrating on a difficult maneuver. So every chance you get, take a deep

cleansing inhale starting in your lower abdomen and exhale through your

mouth. A good deep breath will always

rebalance you mentally.

RIDE YOUR OBSTACLES IN SEGMENTED

PROGRESSION

This is where

really knowing and understanding your horse’s personality will help you with

his training.

Your horse’s training

should always be progressive; when you enjoy any improvement in his

understanding of your requests, take it!

Another small improvement tomorrow is the progression you want.

In the above

video you didn’t see a spectacle of commotion unfold. The horse has been in that concrete pond

before, but he was still somewhat hesitant because it is not mud or rocks as

the ponds with which he is most familiar.

When the horse was hesitant, the rider did not force the issue, but

allowed the horse time to look and get comfortable during a training session.

On the bridge

the rider allowed the horse to stop and stand quietly. Such a maneuver is often asked for in a

competition. Too often, horses want to

rush across the bride and get off. Don’t

allow any rushing of an obstacle when your horse has experienced the obstacle

sufficient times for him to know the obstacle is not the boogey man. Initially, you

might allow rushing as exiting quickly from a bridge is better than the horse lungeing off the bridge sideways. Be careful where you restrain the horse, you

will quiet possibly have to use restraint on an obstacle in segments, as you

build upon the horse’s confidence.

It is often a

good idea to school an obstacle in repetitions.

In the video, the horse was asked to make three laps around the pool and

bridge obstacles. By doing the obstacles

several times in a row, we got small improvements each time, our goal for the

day.

You could

consider the concrete pond entrance another “segment” of your training plan for

that obstacle.

In the video,

when the horse approached the wide side of the pond after the first bridge

exit, he was focused on his task, but not 100% comfortable about entering the

pond. Had you pushed that entrance, the

horse would have responded with more hesitation, not less. I was not going to give the horse that

opportunity. I rode him to the edge, let

him put his head down and look, and then proceeded to ignore the horse and talk

to the videographer. Sensing that I was

not concerned, the horse felt no pressure and stepped right into the pond, in a

slow, thoughtful, safe, inquisitive manner; all of his own accord.

On the second

lap or the next “segment” the horse was asked to enter the water next to the

bridge, not his favorite place. He had a

slight stall, but since this was his second chance, I pushed him forward and he

went with just a little effort. Note on

the third entrance to the pond we increased the degree of difficulty by

entering right alongside that worrisome bridge.

The horse showed no reluctance.

Each time around

and through the obstacle we were building trust with the horse by avoiding any

kind of labor dispute or evasion. The

horse was never pressured into responding, therefore had no reason to refuse

the obstacle. He had a chance to think

about the obstacle, and he decided it was his idea to move forward.

If you can think

and school this way on obstacles, you’ll be progressing in small steps with the

final result being a giant advancement.

During competitions you won’t have an opportunity to make three

different trips into the pond. But it

won’t matter as you will have developed a trusting, confident horse that will

enter water for you, even if he has never seen that particular obstacle before.

Your horse must

always honor your request. If you make

it a demand (on a rare occasion it may need to be demanded) the demand will

turn to defiance and resistance if the horse is not mentally ready to respond

correctly. As the trainer, it is your

responsibility to think through all schooling situations and avoid “demands”

the student cannot accept gracefully. We

want to set the horse up to respond, not resist.

It is always

preferred to make a request the horse can accept, even if there is concern and

hesitation on his part. Simply set him

up for success by requesting a performance for which you have adequately

prepared him.

It is the

“progression of segments” which can make your training program advance without

incident.

ULTIMATE

GOAL: SEAMLESS ENTRACE

Any obstacle,

including water obstacles require a seamless entrance and exit with a steady

unchanging cadence if you are to score well in competition.

In your own mind, you should begin to ride

the obstacle before you get to it, you probably know where your horse will

struggle with the obstacle, so be ready, to help him in the training

process. A good horseman learns when to

push and when to back off mentally and with physical cues.

As you begin the

exit of the obstacle, exhale, but don’t stop riding and don’t let your horse

change cadence. You are not clear of any

obstacle until you are approximately two horse lengths past it. That is typically where the judge will

disconnect the score from the obstacle.

BACKING

IN WATER

A great way to

start teaching your horse to back in water is to stop him with his hind feet

still in a water obstacle while moving forward.

Initially, you will only want to request one step. As your horse becomes more adept and willing

to back in water, you can ask for the second step back, and then another and

another.

Start your

“backing” training in water by being in the water. Many times you may not have level ground,

this is a situation that both you and your horse must learn to adjust for and

expect to happen. It might surprise both

of you, but there is no need to be startled if you are moving slowly and

thoughtfully.

It is best

mentally for the horse if you teach “backing out of water” near an easy

entrance.

If the horse wants to hurry and back quickly,

attempting to clear the obstacle, stop, stand and wait. Don’t let him hurry. No rushing allowed. You may spend more time standing than

backing, which is simply another opportunity to teach your horse to wait for

you, which keeps both of you safe.

Once you have spent as much time as necessary

preparing the horse to back confidently and willingly while in water, you can

then begin to teach the horse to back from dry ground directly into a water

obstacle.

Once the horse

has mastered backing into water, you can begin to teach backing off of ledges

into the water. Something similar to

backing out of a step up horse trailer;

think baby steps, one slow, easy step at a time adds up to success.

In an

effort for Equine Studies Institute to offer continual education, as your

online instructor, I want to give you every opportunity to continue your

training. An onsite clinic planned to

meet your needs is an incredible way to continue training your horse. Clinics can be a lot of fun with great

camaraderie and less pressure than a competitive event and are good stepping

stones towards a competition.

* JoLinn Hoover can answer

your questions and assist you with hosting a clinic. We have worked together many times and can

personally vouch for the Hoover Team’s exceptional training. In addition to helping you with a clinic, The

Hoover Team can also design your obstacle course. You can contact her directly at: info@mjrisinghranch.com 1-541-519-4995.

* Don’t feel up to the effort of hosting a clinic,

but you’d like to ride in one? Contact

Marie-Francis Davis directly at:

mfcdavis@msn.com or lynnpalm.com/clinics.htm Phone toll free 1-800-503-2824.

* Marie-Francis Davis can provide the details on

mountain trail clinics at Fox Grove Farms in

* Wish you had your own obstacle course, but you

can’t afford one or you don’t have a good place to build a course? Investigate the possibilities of working with

a boarding facility, an association, local horse club or city or county recreation

department. (An obstacle course also

works great for dog training and mountain biking). Make it a horse-community project. It can start small and grow as you go.

* Commandeer whoever you can with a tractor or small

back hoe and build your own course. It

is amazing what you can do with a hole, a hill, logs, rocks and railroad

ties. Get the local lumber yard and

landscaper to donate in some way to your project and give them credit for it on

a posted yard sign advertisement.

ASSIGNMENT:

Send me a video of you and your horse negotiating a water obstacle, including, but not limited to:

1.

Crossing water of some form with a log,

or rocks, shrubbery or whatever you can utilize at the entrance or exit.

2. During this

crossing please come to a complete stop at a point that you have pre-designated

in your mind’s eye and stand quietly for 3 seconds.

3.

Where

ever you choose, you can back while in the water and stop. Back into the water obstacle from the edge or

back out of the obstacle, whichever will work better.

4. The obstacle does not have to be

fancy or complicated. I just want to see

what you have accomplished, so I can critique it for you with some additional

training tips specific to you and your horse.

Make certain to title your

assignment in the email and send directly to:

Vikevon7@gmail.com

Please load your videos to YouTube or another host

and send me the “hot” link. I’ll do my

best to respond to your assignment within 5-7 business days.