Equine Coat Color Genetics

Lesson Nine

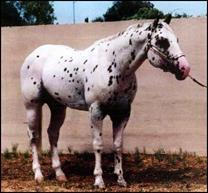

The Appaloosa

Like the terms

“Paint” and “Pinto”, “Appaloosa” refers to both a breed and a color. Like those terms, when capitalized it means a

horse of that breed, and when not, it means the color. Just as the terms “paint” and (more commonly)

“pinto” are used to refer to horses of any breed with white body spotting, so

has the term “appaloosa” been used to refer to that pattern, regardless of

breed. In Europe it is usually called

“spotted”. Although the Appaloosa breed

gave its name to the color, it is far from the only breed in which the pattern

occurs. Spotted horses have been found

in Chinese art dating back as far as 500 BC. By the 1300s they were

common in Spain and by the early 1800s their presence was well established on

the North American continent as the horse of the Nez Perce Indians. Tribal legend of the Nez Perce indicate that

the first '"spotted horses" arrived aboard a Russian ship in the

early 1700s. The horses were traded to Indians in the northwest who in turn traded them to the Nez Perce. Other stories credit Cortez and the early

Spanish explorers with the infusion of the Appaloosa into the Americas in the

early 15th century.

The breed

registry for the Appaloosa horse is the Appaloosa Horse Club (ApHC)

http://www.appaloosa.com/

This registry

has standardized names for the various types of appaloosa patterning and

characteristics, as the Paint and Pinto registries did with pattern names like tobiano, overo, and so on.

As with the pinto spotting patterns, the size of the white areas is

independent of the actual pattern gene, so can vary from large to small.

A group of

researchers and Appaloosa breeders formed a project to identify and map the

Appaloosa genetics. You can read more on

The Appaloosa Project at: https://www.appaloosaproject.co/

Appaloosa Characteristics

Just as the Dun

gene causes a set of specific “dun-factor” markings, and the Champagne gene

causes a unique skin color, the appaloosa color comes with some special characteristics

of its own, in addition to any colorful pattern the horse may carry (or

not). These characteristics are varnish

roan, mottled skin, white sclera, and striped hooves. Another characteristic which is quite common

but not universal is a short, sparse mane and tail (in the Appaloosa breed this

is often called a “rat tail” and is considered a sign of “old blood” or

“foundation” type); this trait is one that most breeders have been trying to eliminate,

with some success, so it apparently is not caused by the actual appaloosa color

genes.

Mottled Skin

This

characteristic is unique to the appaloosa color, and is visible wherever there

is bare skin - on

the face, udder or sheath, and under the tail.

It can vary from horse to horse, and can also increase over time, but

there should be at least some mottling present.

Not to be confused with the speckled champagne skin, which is pinkish

with tiny dark spots that look like they were dabbed on with a brown or black

felt-tip marker, the appaloosa mottling looks like pink spots on a dark

base.

White Sclera

The sclera is

the white part of the eye which encircles the iris (the colored portion). The

white sclera of the human eye is visible all the time, but horses typically do

not have much white sclera visible unless they are looking forward or back. The appaloosa's is more readily visible at all

times. While the visible white sclera is

considered an appaloosa trait, by itself it is not sufficient to prove a horse

is appaloosa, because it can occur randomly on other colors and breeds,

especially if there is a large amount of white on the face.

Striped Hooves

Bold

and clearly defined vertical stripes on the hooves of the dark legs, either

dark with tan stripes, or tan with dark stripes, is an appaloosa trait. If the horse happens to

have white markings on its legs (unrelated to its appaloosa color), those

hooves won’t be striped. Striped

hooves alone are not proof of appaloosa color, because other things can cause

them. Some Cream dilutes have vertical

stripes on their hooves, but this is much more subtle. Silver dapples can have very bold, distinct

stripes, especially when young. When

horses with white leg markings have ermine spots in them,

that can create a stripe below each spot. For comparison, here are some examples of

non-appaloosa hoof striping.

palomino striped

hoof silver dapple striped hoof ermine spots with stripes

Varnish roan or

“appy roan”

Appaloosas

have a specific type of roaning which is different

from the true roan and other types of roan that we discussed earlier. This roaning is

typically called Varnish Roan. Appaloosa

roaning is somewhat like grey in that it is

progressive over time (although the horse won’t go completely white as a grey

would). They start out dark, like a

grey, and the roaning increases from year to

year. Like grey, it may be obvious at

the first shedding, or they may stay dark for several years, but eventually it

will occur. Although the appearance can

be mistaken for other types of roan, or even grey, there are differences. The lightest area tends to be over the hips

(which may or may not be spotted), and the roaning is

not as uniform as other types of roan.

There are darker areas where the bones are closer to the skin, such as the

point of hip and elbow, stifle, lower legs, the frontal bones of the face and

above the eye. The ears are also usually

dark. These areas may stay dark all the

horse’s life.

Varnish

roan

Appaloosa Patterns

In

addition to the above general appaloosa characteristics, appaloosas usually

have some sort of pattern. Some don’t,

and are “only” varnish roan, but the patterning is highly desirable and

breeders strive to produce them.

Just

as the Paint and Pinto registries standardized pattern terms such as Tobiano and Overo, Appaloosas have their own pattern terms

as well. (In other breeds where these

patterns occur, they may or may not use the same terminology, but for the most

part they have been pretty universally adopted.) White patterning that covers all or almost

all of the body is called Leopard, while white patterning that covers the

hindquarters is called Blanket. The

white areas can contain spots, or not (more on that later). A leopard without spots is called a

“few-spot” and a blanket without spots is called a “snowcap”.

Leopard

is used when the horse is 60% or more white.

It’s not uncommon for them to retain a good deal of dark color on the

head and legs. If the white patterning

extends up onto the neck and shoulder, but doesn’t cover them entirely, this is

commonly called a “near-leopard” or “suppressed leopard”.

Leopard Near-leopard

“Few-spot”

leopard Few-spot

Blanket is used for a white marking

that does not go farther forward than the withers. They can be just a small area on the top of

the hips, or extend all the way down under the belly. The Appaloosa registry has five

classifications of blankets depending on how much of the body they cover.

Small blanket Larger blanket

Snowcap

Snowcap

Another pattern is called

Snowflake. This is not actually white

patterning, and it’s not known what exactly causes it; most likely it’s a stage

that some varnish roans go through, but that is not known for certain yet. This is when there are many white spots on a

dark background.

Snowflake Snowflake

How it works

The Appaloosa coloring is a bit

more complex than any others so far. The

reason for this is because it’s not just one gene. Think back to when we looked at the base

colors, and remember how it takes a combination of two separate genes to get a

bay – at least one “E” so that it can make black pigment, and then at least one

“A” so the black is restricted to the points, instead of covering the whole

body. Recall how a red horse might have

any of the different genes at the Agouti locus, but because there’s no black

pigment for it to act on, there’s no visible effect. The appaloosa colors are similar to

that.

The first gene is called “LP” for

Leopard Complex. It was named long ago,

before much was known about genetics, and is actually a slight misnomer now –

this is the gene that gives the appaloosa characteristics listed above – the

mottled skin, visible sclera, striped hooves, and varnish roan. It does not actually cause

the pattern labeled Leopard. LP is the

basic appaloosa gene, without which a horse would not be any of the appaloosa

colors, but additional genes are needed to get the white patterning. Without those pattern genes, the horse will

be “just” a varnish roan with appaloosa characteristics. The LP gene is another incomplete

dominant. This should be a familiar term

by now. When heterozygous, any white patterning

on the horse will contain dark (base color) spots that do not roan out over

time as the varnish roan progresses (these would be the leopards and

blankets). When homozygous, the white

areas will have no spots or only a few little ones (these would be the fewspots and snowcaps).

Some experts also state that the heterozygous ones have dark hooves with

light stripes, while the homozygous ones have light hooves with dark stripes

(on legs without any white markings, of course).

When homozygous, the LP gene also

causes night blindness (full name: Congenital Stationary Night Blindness). Most horses see much better

in the dark than humans, but horses with night blindness see very little in the

dark. Surprisingly, they seem to cope

with this very well, as with the Splash pintos that are deaf. It took a long time for us humans to realize

that these horses were deaf, or night-blind, as the case may be. This condition is in place from birth and

does not change throughout their lives.

It is commonly believed that

appaloosas in general tend to be more prone to uveitis, another eye condition,

but there is no solid evidence linking it to the appaloosa genes. Most experts think it’s caused by some sort

of virus, but it’s not known why appaloosas would be more susceptible.

The LP gene is located on

chromosome 1, and was isolated in 2013.

There is now a test for it.

But in addition to LP, an entirely

different, separate gene is needed to get the white patterning. So far only one has been isolated, in 2015. It’s located on chromosome 3, and was named

PATN1. It is a simple dominant. PATN1 causes the leopard/fewspot

pattern, defined as 60-100% white. Like

the various pinto-spotting genes, there are undoubtedly other factors that

influence the amount of white. Usually

leopards are white all over the body, with some dark on the head and legs. But some have mixed or even dark areas

extending back from the head, even including the whole neck and chest

sometimes. These are commonly called

“semi-leopard” or “suppressed leopard”.

In the past it could be hard to tell for sure whether a horse was a

semi-leopard or an extended-blanket pattern, but now that there is a test for

the PATN1 gene, this can be determined.

A horse that has one or two PATN1 genes, and one LP gene, will be a

leopard appaloosa: white covering all or

most of the body, with dark (base color) spots scattered throughout. The spots are often larger and more numerous

over the hindquarters. A horse that has

one or two PATN1 genes, and two LP genes, will be a few-spot appaloosa: white covering all or most of the body, with

no (or a very few small) spots. A horse

that is homozygous for both, LP/LP + PATN1/PATN1 will, when bred to solid

mates, produce 100% leopard patterned offspring.

When the research into the pattern

genes was underway, it was hoped that there would be a second gene (which would

be named PATN2) that causes the blanket pattern. Unfortunately, no such gene has been found. The researchers now believe that the blanket

patterns are probably caused by many pattern genes, each of which has a small

effect, so that a horse with a very small blanket might have just one of these

genes, while a horse with an extensive blanket would have several of these

genes. And such a horse could pass on

none, or some, or all of them, so that its offspring would range from no

blanket, through various sizes of blankets, to ones that looked the parent,

with smaller numbers at each extreme.

This does appear to be the way they produce. But these pattern genes have not been

identified yet. It may be that some of

the white-spotting (“W”) genes in the KIT complex can affect appaloosa patterns

as well.

There

is a nice article on the Appaloosa Project website which has illustrated

Punnett Square examples demonstrating the odds of various results when breeding

Appaloosas, here:

The interesting thing about this “two-genes-needed”

inheritance of the appaloosa color, is that horses can

carry the various pattern genes without showing any outward sign of it, if they

don’t have at least one LP gene. We have

seen similar situations before; for instance a red-based horse can carry a

Silver gene without showing it, even though it’s dominant, because Silver only

affects black pigment and the red horse has none. And as previously mentioned,

a red-based horse does not show which genes it carries at the Agouti locus,

since they too only affect black pigment.

It is completely unknown what percentage of solid-colored horses in

breeds that once came in appaloosa colors but no longer do,

or which go back to “unknowns” fairly recently, could possibly be

carrying PATN1 and whatever other patterning genes that cause the blanket

pattern. It explains how the rare

“crop-out” appaloosa can appear in breeds that were thought not to have those

colors, such as the Quarter Horse and Tennessee Walking Horse. One parent carried the pattern gene, unseen

for generations, and the other parent had the LP gene although misidentified as

a regular roan, or thought to be grey, or even covered up by an actual grey or

roan color. The foal gets both, and -

surprise – an appaloosa baby.

As mentioned at the beginning, the

appaloosa coloring is very old. It

appears to have been popular at various times in history, and then fallen out

of favor at other times. While it would

be easy enough for a breed to eliminate LP because it’s visible (especially if

that breed didn’t have any roans or greys for it to be mistaken for), the PATN

genes would not be as easy to remove from the gene pool, since they are invisble without LP.

It would be a fascinating project to test a large number of solid

colored horses from breeds which once had the coloring, or ties to breeds that

did, and see if any are carrying PATN1.