Equine Coat Color Genetics

Lesson Five

Wrapping up Dilutions

You will remember that

the term “dilute” is used to describe many colors: basically any of the colors that result from

a dilution (lightening) of the color.

These are all caused by different genes.

We have already covered Cream, Dun, and Champagne. In this lesson, we will cover Silver, Pearl,

and talk about various mixtures of two or more dilution genes.

The

Silver (AKA Silver Dapple) gene

Silver is a simple dominant; there

is no visual difference whether the horse has one Silver gene or two. The symbol for this gene is "Z"

(nobody seems to know why that letter was chosen, but "S" would have

been confusing since many colors begin with that letter, and maybe just about

everything else was taken). The gene was

isolated in 2006, and there is now a test for it.

This color has been known for 30

years or more, but is only recently becoming better understood. The name Silver

Dapple was originally applied to Shetland Ponies, in which the color is fairly

common (at one time it was even thought that the gene only occurred in

Shetlands), because it frequently has the extremely dappled, greyish body color

with silver-white mane and tail in that breed. Now we know that not all

(possibly, not even most) of them are dappled, so the name has been shortened

from Silver Dapple to just Silver. The term "Silver" has been

confusing to some, who expect to see a grey-toned horse perhaps, but it has

been in use too long to change. In Australia the color is called

"Taffy", but the term has never caught on elsewhere. In some of the

breeds in which Silver is common in the USA, such as the Rocky Mountain Horse,

it is called "Chocolate".

Except in the few breeds where it is common, they are almost always

registered as chestnut.

This color is not frequently seen

except in a very few breeds -- the Shetland, Mini, and Icelandic have quite a

few, and there are a few breeds in the USA which have purposely selected for

the color so that now many horses of those breeds, perhaps even most in some

cases, are silvers: the Rocky Mountain Horse, Mountain Pleasure Horse, and

Kentucky Mountain Saddle Horse. Aside

from those breeds, it is not a very common color, but it does occur in the

Welsh Pony, Welsh Cob, Quarter Horse, Paint, Appaloosa, Morgan, Saddlebred,

Tennessee Walker, Missouri Foxtrotter, Bashkir Curly,

Mustang, Dutch Warmblood and Paso Fino. There are

even reports of it possibly occurring in the Arabian, but these have never been

proven. It is thought to have been in

the Friesian breed in the past, but no longer. It also is known to occur in

some draft breeds such as the Belgian, Breton, Comtois,

Noriker, and Italian Heavy Draft.

How it works

The Silver gene is interesting

because, unlike Champagne and Dun, which we covered last time, Silver is more

like Cream in that it is pigment-specific.

Silver dilutes only black pigment. Thus, the Silver gene can be carried

and "hidden" by a chestnut horse (since it has no black pigment to be

diluted), and in this way it can appear to skip generations, even though, like

any dominant gene, one parent must have the gene in order for the foal to have

it. It is like the opposite of Cream,

which only dilutes red pigment when heterozygous, and thus can be carried and

"hidden" by a black horse.

When a horse gets the Z gene,

any black pigment will be diluted to a chocolate-brown, ranging in shade from

taupe or "dead grass" color through mocha-brown to deep chocolate

brown, often with a bluish cast. It can be hard to tell apart from a dark liver

chestnut, but usually the dark chestnut will have reddish undertones and the

Silver will not. The gene tends to

dilute the mane/tail much more strongly than the body, often to a silvery-white

color, although this can vary and they may darken with age. Silvers often have

a distinct "face mask" of darker hair which is helpful in identifying

them. This "mask" generally covers the forehead, around the eyes, and

down the front of the nose. They also

tend to have lighter hair on the lower legs, lightest close to the hooves. Another interesting feature of this color is

that it is very often markedly different in summer and winter coats, or if a

horse is clipped.

Silver on Black

Silver on a black base color is the

shade that comes to mind first when hearing the term "Silver Dapple".

The body color is diluted to a chocolate-brown or mocha-brown shade, sometimes

light enough to appear similar to a sooty palomino. The mane and tail are often

near-white, a striking contrast. The lower legs are usually lighter than the

rest, almost flaxen near the hoof, and the lower legs are often dappled (which

is highly unusual in other colors). The mane and tail often have dark roots. In

a horse with the "classic expression" of Silver Dapple, there will be

very distinct and strong dappling present, which, unlike most colors, does not

appear to be related to age or condition, but rather stays fairly constant

throughout the horse's life -- although they may vary with the seasons, appearing

on the summer coat but not the winter coat, usually. But not all Silvers show

the dappling. Some are a flat chocolate-brown color all year round. Silver on

black can be hard to tell apart from a dark flaxen liver chestnut, and in most

breeds they have indeed been registered as "chestnut" because nobody

knew what they were. Some clues to look for would be the dappling, a drastic

change in color from winter to summer, a bluish cast rather than a reddish

tone, and a silvery mane/tail rather than golden-hued flaxen. Still, it may be

impossible to tell the difference by looking.

Thankfully, there are now genetic tests that will tell for sure. The

normal name for this color is "Black Silver", but sometimes you might

see them called "Classic Silver Dapple", "Chocolate

Silver", "Chocolate", or just "Silver".

Typical

Black

Typical

Black Silver

Silver on Bay

The Silver gene acting on a bay

base color gives a quite different effect. The red pigment on the body is unaffected,

while the black on the legs is slightly diluted and the black of the mane/tail

is more strongly diluted. This gives the appearance of a horse that is not

quite bay, and not quite chestnut either. Most of the time they end up being

registered as chestnut, which can cause confusion, but most registries have no

separate category for Silver. The mane and tail can vary from a platinum

blonde, to a flaxen color, to just slightly diluted, and can darken

considerably with age, making identification more difficult. Usually the legs

are the main clue that the horse is not a chestnut -- they will be much darker

than a chestnut, ranging from near-black to chocolate-brown, generally with

lighter hair close to the hooves. And again, when in doubt, testing will

distinguish them from chestnuts. The most usual term for this color is

"Bay Silver" or “Silver Bay”, but occasionally they are called

"Red Silver" (reflecting the reddish body color), however, this is

discouraged, since to most people the term "red" means chestnut, and

therefore "red silver" could cause confusion to those thinking that

it means silver on chestnut.

Typical Bay

Bay Silver

Bay Silver

Silver on Brown

A seal brown with the Silver gene

will look similar to either a black silver, or a bay

silver, depending on how light or dark the brown's base color happened to be.

Most seal browns are mostly black, and this plus Silver would probably be very

hard to tell apart from black silver. There would likely be some tan on the muzzle

on close inspection. The lighter seal

browns with more tan in the coat would give a lighter

shade of Silver. Testing for the different Agouti genes might be needed to be

sure. The most usual term for this color

is "Brown Silver" or “Silver Brown”, but if the exact agouti genes

are not known, they might be called by whichever they looked most like, i.e.

Silver Bay or Silver Black, or just called Silver Dapple.

Typical Seal Brown

Brown Silver

Silver on Chestnut

Since a chestnut horse (or any

other red-based color) has no black pigment to be affected by the Silver gene,

they will show no effects. Such a horse would be called "chestnut carrying

silver". Some breeds use the term "Silver Chestnut" but this is

highly discouraged by geneticists, because it tends to confuse people, making

it sound like the chestnut horse is somehow affected by the Silver gene. In

some breeds, some breeders apparently think that the Silver gene can cause a

flaxen mane/tail on a chestnut horse; however, this is not true.

Foal colors

Foals often have hooves with a very

strong and distinct striping pattern, and white eyelashes. These traits are

helpful for identifying Silver in foals, but are gradually outgrown most of the

time. Bay and brown silvers generally

look chestnut as foals, and black silvers typically are a greyish color at

birth. The diluted mane and tail may not

come in for some time. One thing that is

helpful in identifying Silver foals is the fact that they will be born with

black skin (since they have an “E” gene) rather than pinkish skin which is

typical on chestnut (or other “e/e”) foals at birth. Now that the gene has been isolated, of

course, we can test for it and not watch and wait and wonder!

Breeding for

these colors

As a simple dominant, only one gene

is needed to get the color. Therefore,

you have a 50/50 chance of getting it when breeding a

heterozygous Silver to a nondilute.

Punnett Square example:

|

|

Z |

z |

|

z |

Z/z |

z/z |

|

z |

Z/z |

z/z |

And when breeding two heterozygous

Silvers, you will get 25% homozygous Silver, 50% heterozygous Silver, and 25% nondilute.

Punnett Square example:

|

|

Z |

z |

|

Z |

Z/Z |

Z/z |

|

z |

Z/z |

z/z |

However, because of the

pigment-specific action of this gene, when a chestnut is involved, it can mess

up the percentages. A chestnut can carry

the gene, but won’t express it. So if you

have, say, a black silver who is “E/e”, bred to a black who is also “E/e”,

rather than the straightforward 50-50 chance of black or black silver, you

instead have a 25% chance of chestnut (half of which will have the Silver gene,

but not show it), 37.5% chance of black, and 37.5% chance of black silver.

The Pearl

Gene

Pearl is a fairly newly discovered

gene in the dilution category. This gene

is almost certainly a third allele at the Cream locus, but at this time the

research showing that has not been published.

We should assume it is, until proven otherwise, since the evidence is

quite strong. U.C. Davis, who developed

the test, is calling it "Prl". The test has been available since October

2006. This gene is not quite a simple

recessive gene, but almost. It normally

requires two copies to be visible by itself, but it also is visible when one

Pearl is combined with one Cream allele.

History:

In November of 2001, the registrar

of the Champagne registry (ICHR), Carolyn Shepard, received an application for

a Paint horse named "Barlnk Peachs

N Cream". She looked for all the world like a gold champagne, complete with golden

coat, pink skin and freckles. Just one

problem -- her parents were both "sorrel". It's not all that uncommon to find a gold champagne that was registered as chestnut/sorrel,

likely as young foals while still in their darker baby coat, or maybe they are

a particularly dark shade. But in those

cases usually the horse will have a champagne parent, or other champagne

offspring. This was not the case with

these parents. No other explanation

could be found, though, and it was before any tests for these genes were

available. So the horse was given a

"tentative" number (meaning she would have to prove she was truly

champagne before being officially registered).

But this oddity sent Carolyn Shepard on a quest, and what she found was

that there were increasing incidences of "palominos" popping up from

two "sorrel" parents, and double-dilute-looking foals from one

non-dilute parent. What they all had in

common was that they were descendants of a horse named Barlink

Macho Man. She was convinced that this

was a new gene. She called it the "Barlink Factor" and by July of 2002, had figured it

out enough to write an article about it (which is still available on the ICHR

website).

Meanwhile, some odd-colored horses

were popping up occasionally in the Andalusian and Lusitano

breeds. It was hoped that they might be

champagne, which is what they looked like, but as with the similar Paint horses,

no champagne ancestor could be found, and they didn't reproduce the color as

expected. Eventually it seemed there was

no other explanation than that this was a previously unknown dilution gene. By consensus of those researching it, it was

called "Pearl". You can read

more about the process of finding and identifying these horses at www.newdilutions.com .

The genetics researchers at U. C.

Davis heard about the "Barlink Factor" and

wanted to try to find the gene. Carolyn

Shepard, by that time, was certain that it was an allele at the Cream locus, or

perhaps a gene right next to it, because by then there were several known

"Barlink Creams" which were thought to be cremello/perlino but did not

produce like one -- instead of having 100% diluted foals, they were passing on

only the Cream, or only the "Barlink

Factor" (which caused an undiluted-looking foal) -- never both at the same

time. She told the lab at U.C. Davis

about her theory and told them where to look for the gene. And, sure enough, they found it in record

time. (By comparison, all of the other

color genes that have been isolated took several years of searching.) They announced that a test was available in

October 2006. They would not call it

"Barlink" since the owner of the Barlink-related Paint horses was against the idea, and

also, by then it had been found to have come from the mare My Tontime (granddam of Barlink Macho Man).

U.C. Davis proposed calling it "apricot", to howls of disgust

from horse owners and color researchers everywhere. But a surprise was yet to come. In late October, they tested a hair sample

from a "pearl" Andalusian, and it turned out to be the same exact

gene! So, to the relief of all

concerned, they settled on "Pearl" as the official name for the

gene.

Some would say that the gene is not

"official" yet because they have not yet published the study. But many horses have now been tested, and the

results have all been consistent with their phenotypes and pedigrees. It's also not considered "official"

that the gene is located at the Cream locus, because U.C. Davis has not yet

confirmed this in writing. But those who

have researched this color extensively are 100% sure that it is. There have now been a large enough number of

horses with offspring to say that the Cream/Pearls have never been observed to

pass on both genes, only one or the other. And no horse has ever been found to have two Cream plus one Pearl, or two Pearl plus one Cream. By now most feel the evidence is overwhelming, it just can't be stated "officially for

sure" until that study is published.

So far the Pearl gene has been

documented in the Paint horse (so far only in descendants of My Tontime), the Andalusian/Lusitano

(in both America and Europe), the Peruvian Paso (in 2006) and the Gypsy Cob (in

2007). Undoubtedly more will follow, now

that the test is available to identify carriers. We would expect to find it in breeds with

Spanish influence, such as the Mustang, Appaloosa, and Quarter Horse, and

possibly some of the gaited breeds. It

is presumed to be a mutation of the Cream allele that happened at some time in

the Iberian breeds, and from there spread to America. It does appear to be quite rare, but

considering how it can be carried for many generations without being visible,

it is unknown how widespread it might be.

How it works

All of the dilution genes have

something that makes them unique, and Pearl is a quirky one. It does not appear to be pigment-specific

like Cream and Silver, that is, it dilutes both red and black pigment equally

(like Champagne and Dun). It does not

leave the points dark, or put stripes on the horse, like Dun. It does dilute the skin color, like

Champagne. But it only causes a visible

dilution effect when there are two Pearl genes, or one Pearl and one Cream.

One Pearl gene by itself does not

dilute the base color, although the horse will usually have pink speckles on

the skin. These are not always present,

and may come and go over time, so it's not a definitive indicator of the gene,

but it is commonly seen. One Pearl gene

does not appear to have any additional diluting effect on horses with another

type of dilution gene. It does not

create a “double diluted” look when combined with Champagne, as Cream

does. There are a few documented Pearl +

Champagne and Pearl + Dun horses, and they don’t look any different from ones

with no Pearl.

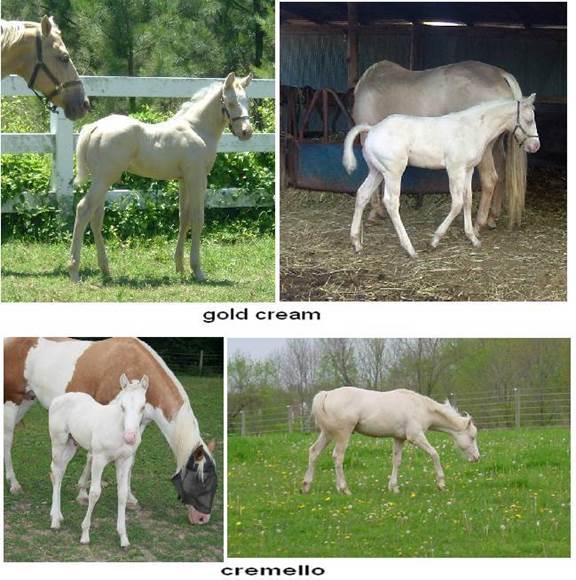

One Pearl gene plus one Cream gene

gives a horse that is usually born looking like a cremello

or perlino, but looks more like a champagne-cream as

it gets older. They often have light

colored eyes (but not typically bright blue as adults), and they have pink skin

like a champagne. These horses are

easily mistaken for double-cream dilutes or champagne creams. On a red base, they look like a cremello or a gold cream.

On a bay/brown/black base they look very much like a perlino

or light amber cream.

Two Pearl genes will dilute both

the hair and skin so that the horse looks remarkably like a

champagne. Most of the ones that

have been found are on a chestnut base (since that color is so common in the

Paint breed) and they look like a gold champagne. They are golden, with pink skin and

freckles. They have been registered as

palomino. A homozygous Pearl on other

base colors looks very similar to a champagne of that

shade.

Breeding for these colors

When breeding two heterozygous

Pearl carriers, which carry no other dilution genes, together, there is a 50%

chance of getting a Pearl carrier, 25% chance of getting a visible Pearl color,

and 25% chance of no Pearl gene. This unexpected

result is what led to the discovery of the new gene. When people started linebreeding to the

popular stallion Barlink Macho Man, these “palominos”

from two apparently sorrel parents, and “cremellos”

with only one dilute parent, started popping up.

When breeding a heterozygous Pearl

carrier to a heterozygous Cream color, you have a 25% chance of getting both

(the horse would appear cremello/perlino),

a 25% chance of single Cream dilute with no Pearl, a 25% chance of a Pearl

carrier with no Cream (will not be visibly diluted), and 25% chance of no

dilution genes.

If that Cream + Pearl horse (which

generally has the phenotype of a double Cream dilute) is bred to a nondilute, he will pass on either the Cream gene (giving a

single Cream dilute phenotype) or the Pearl gene (giving a nondilute

phenotype), because these genes are at the same locus, which means any horse

can pass on only one to each foal.

Double Pearl on chestnut. Bother parents are normal-looking chestnuts,

who carry a Pearl gene.

Another Double Pearl on chestnut, but a much lighter shade.

Close-up of skin color; very champagne-like.

Dilution Mixtures and Confusion

When a horse happens to inherit

more than one type of dilution gene, the results can be highly variable. Some of them combine to give a “double dose”

effect, while others have no visual effect at all. Some combinations even tend to create a

darker color than either one would give alone, oddly enough.

Silver Combinations

When Silver and Cream are both

present, the effects of the Silver gene tend to be less obvious,

or even not really visible at all. This

would seem to be counterintuitive since Cream makes the mane and tail of a

palomino white, and Silver makes the mane and tail of a black silver white (or

nearly white, usually), but oddly enough they seem to almost cancel each other

out instead of doubling the dilution effect.

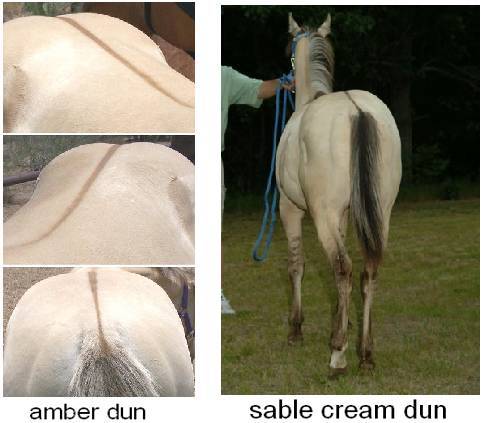

When Silver is combined with Dun,

the horse will usually have about the same body shade as with Dun alone, with

the darker dun-factor markings, but with a light mane and tail like a typical

Silver, and the black on the legs will be somewhat diluted and often dappled or

mottled. (A red dun would of course show

no visible effects.)

When Silver is combined with

Champagne, it gives a boost to the overall level of dilution (although not to

the same extreme as combining Champagne and Cream) and dilutes the mane, tail,

and legs. The examples that have been

found so far are similar in shade to a smoky cream. Unless it is known for certain which

dilution genes are present in the parents, only genetic testing can sort these

out, since they look very similar.

Amber champagne plus Silver

Dun vs. Buckskin vs. Dunskin

Probably one of the biggest areas

of confusion is in this group of colors.

Throw in a few amber champagnes and it gets even worse. Part of the problem comes from the fact that,

for many years (and even today in some places and some breeds) all kinds of

dilutes were lumped together under the name of "dun". So when you hear someone say "I didn't

know I could get a palomino foal from a dun," well, technically you

can't... but since buckskins are/were commonly called dun, suddenly it makes

perfect sense.

If horses followed all the

"rules" it would be much easier.

Things like "all champagnes have pink skin" (they do, but it

can look awfully dark from a distance and in photos, especially when heavily

freckled by the sun). Or "duns have

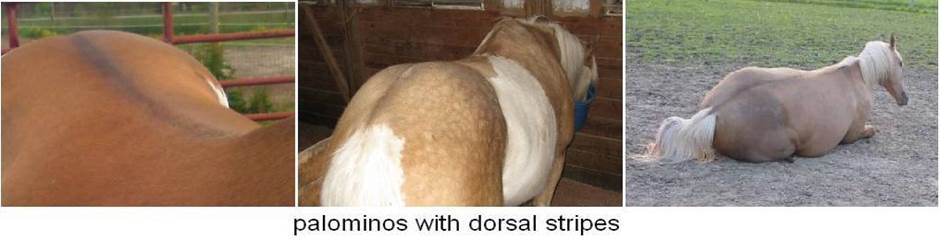

dorsal stripes and buckskins do not" (not so, buckskins can have

surprisingly dark dorsal stripes on occasion).

Or, "it's not a dun if it doesn't have leg

barring" (generally true, but sometimes those markings are obscured by

pinto spots, or invisible on a really light color like cremello).

Usually looking at the pedigree can

be helpful when there is doubt. Some

breeds only have one or the other kind of dilution, and in others there are

well-known lines of dun and cream and champagne. Assuming the pedigree is correct (no

"fence jumpers"), this can often be all the

info you need. Other times it's just not

known which kind of dilute the ancestors were, or maybe they were both.

Duns and dunskins

will have the dorsal stripe and leg barring (unless there are white markings

covering those areas). A dun dorsal

stripe tends to be more reddish colored, very sharp-edged (typically people say

it looks "painted on" or "like it was drawn with a

Sharpie"), slightly wider over the loin area, and runs right down the

center of the mane and tail. A non-dun

dorsal stripe tends to be black in color, be the same width throughout, be

rather fuzzy-edged, and sometimes comes and goes with the seasons.

Probably the main thing to look for

to identify a buckskin with a dorsal stripe is the

lack of any leg barring. If there is none, that pretty much rules out dun. But if the horse has some ambiguous

"mottling" on the legs, or high white that covers that area, then the

only way to know for sure would be by testing.

Thankfully, we now have a dun test!

Regular bay duns and dunskins can be impossible to tell apart by appearance

only. Dunskins

tend to be lighter in general, but there's such a wide range of shades from

light to dark in both colors that they do overlap quite a bit. Sometimes the pedigree will have the answer

(i.e. if one parent was a cremello or perlino, there must be a cream gene, etc.) but sometimes, testing is the only way to know for sure.

Buckskin

dorsal stripe

Dun dorsal stripe

Palomino vs. Dunalino

Palominos sometimes have dorsal

stripes, but it's usually the dark, sooty ones that show these, and they are

not sharp-edged stripes. Dunalinos are often somewhat lighter than the average

palomino (depending on the shade of chestnut that is their base color), usually

with a somewhat muted “peachy” tone, have distinct red-colored dorsal stripes,

and red leg barring. Some dunalinos are the same shade as a regular palomino (perhaps

these would have been darker palominos if they didn't have a dun gene), and the

dun-factor markings are only noticeable on closer examination. It's also worth mentioning that, in some breeds,

owners of dunalinos are not willing to accept or

disclose that fact, preferring to call them palomino. (There is a Palomino registry that does not

accept dunalinos.)

And for registration purposes, they have to choose whether to call them

palomino or red dun. It is very rare for

a dunalino to appear "sooty". It does happen occasionally, but usually just

in foals during a shedding phase. They

are also hardly ever dappled.

Dunalino dorsal stripe

Dunalino

Grulla vs. Smoky Grulla

These two colors cannot be told apart

by appearance only. Smoky grullas may be somewhat lighter, but not always. Many are just as dark as regular grullas. The only

way to know for sure is if one parent was a double-cream-dilute, or if the

horse has produced a definite cream dilute foal, or if it has been tested.

Grulla vs. Smoky Black

These two colors in theory should

be pretty easy to tell apart, but it's an unfortunate fact that many smoky

blacks have been registered as grulla over the

years. So, if you see "grulla" in a pedigree, it may require a little more

research to be sure that it was in fact a dun-dilute and not a

cream-dilute. Smoky blacks can do a very

good grulla imitation at times. Especially as foals, when

they may have "foal-coat markings" that often look a good deal like

dun-factor markings (but they go away when the foal-coat is shed), or when they

are sun-bleached. Here is a

picture of three smoky blacks and one grulla. Can you tell which is which? On close inspection it's easy to tell that

only one has a dorsal stripe and leg barring, but from a distance or in

pictures, it's not so easy. (The second

from the left is the grulla.)

Champagne Mixtures

Once you see a

champagne up close in person, you will never again understand how anyone

could confuse them with a cream or dun dilute.

The skin color is just so totally different. But if all you have is a photo, it can be

hard to tell. Pictures can be

deceiving.

When champagne is combined with

cream, it often produces a pretty good imitation of double-cream-dilutes. The illusion is strongest when they are

foals. As they mature, the eyes will

change from blue to amber, and the skin will begin to freckle. Interestingly, many champagne creams have

even more and darker freckles than regular champagnes.

When champagne is combined with

dun, the results are what you'd expect -- a champagne

colored horse, usually lighter than normal, and with all the dun-factor

markings. Where it gets interesting is

when cream is added to the mix as well.

It would seem logical that the champagne/dun/cream horses would be

lighter than the champagne/dun ones, and sometimes they are, but it's not

always the case. Some champagne/duns are

in fact lighter than some champagne/cream/duns.

It must be that the range in shade from light to dark of the base color

causes these mixtures to have overlapping phenotypes. So, in cases where either one is possible

from the pedigree, the only way to know for sure is by testing them.

Chocolate Palomino vs. Silver Dapple

vs. Flaxen Liver Chestnut

These colors can look remarkably

alike, for such very different things.

They can readily be sorted out with genetic testing nowadays,

thankfully. No more guesswork like in

the past, or waiting to see what kind of foals they produce. But if you are looking at a horse where

testing is not possible and you just want to make the best possible guess, here

are some clues to help figure it out.

Silver dapples don't always have

the dapples for which the color was named, but when they do, the dapples are quite

vivid and clear, and often continue down onto the lower legs (something quite

rare in any other color). Chocolate

palominos are often, but not always, dappled as well, but these dapples tend to

look more like "normal" dapples and often change with the

seasons. Dapples seem less common on

liver chestnuts. Silver dapples often

have dark roots in the mane/tail hair.

And the "tone" of the color will often give a clue. Silvers usually have a "cool tone"

to their coats, with an almost bluish cast, with manes and tails typically

described as "silvery" or "platinum" (although they can be

quite dark too). Chocolate palominos

usually have a yellowish tone, often with lighter golden shading on the face,

with manes and tails that are white but often with varying amounts of dark

sooty hairs mixed in. And liver

chestnuts usually have a reddish tone to their color, and typically a more

yellowish tint to the mane/tail color.

In the days before genetic testing

was available, the only way to sort these out was by close examination of the

individuals, their parents and siblings and offspring, and looking for patterns

in their pedigrees. (For instance,

silver dapples registered as chestnut can be the cause of a bay from two chestnut

parents – which would be impossible if they were truly chestnut, and a

“chestnut” producing a cremello must be a dark

palomino.)

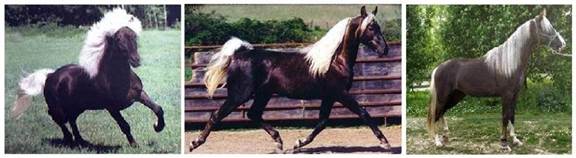

Which is

which??

From left:

silver dapple, chocolate palomino, liver chestnut

Click Here To Take Quiz