Equine Coat Color Genetics

Lesson Four

Dun and Champagne

The

Dun and the Champagne dilution genes are two entirely different, separate

genes, but they do have one thing in common – they are both in the “simple

dominant” category. You will remember that

this means that it takes only one copy of the gene to get a visible effect, and

that there is no difference in appearance between heterozygous and homozygous

(one copy or two). And unlike some other

dilution genes, these two genes affect both red and black pigments, so they are

expressed on any base color, and cannot “hide” on any of the base colors. Because they are dominant, they cannot skip

generations; a dun horse must have at least one dun parent and a champagne

horse must have at least one champagne parent.

But there are occasions when the gene may not be visible. A horse that is also grey, for instance, will

eventually look white, leaving no clue about its base color. Some pintos have so much white that the base

color is impossible to determine. And

some cases of multiple dilution genes make it hard to tell (i.e. a cremello or perlino probably will

not show any visible signs of dun or champagne if they have it). In those cases, or if a horse could be

homozygous, the test will be very useful.

The Dun

gene

The

Dun gene is one that affects both red and black pigment equally, lightening red

hair to a peachy or pale-red shade and black hair to a mousy-grey or almost

blue-grey tone. The skin and eye color

are not diluted. (The dilution effect is

thought by some to be caused by the pigment being restricted to one side of the

hair shaft, rather than an actual lightening of the pigment itself, but this

theory is not proved or disproved yet.)

Dun is unlike any of the other dilution type genes in that it is

"location-specific"; that is, it dilutes the hair on the body, but

leaves the points (lower legs, mane, tail) undiluted. It also is unique in that it causes various

markings that are collectively referred to as "dun-factor" or

"dun-markings". These include

a sharp, clear dorsal stripe, striping or “barring” on the upper legs,

"frosting" on the outer edges of the mane and tail,

"cobwebbing" (concentric circles of darker hair) on the forehead,

white or light eartips, "zippers" (thin stripes of lighter colored hair running vertically down the

back of the lower legs), and dark shading or striping over the withers and/or

lower neck. There is often a darker

"masking" on the face. All

duns will have the dorsal stripe and leg barring at least, but the other

markings are variable from one individual to another. Not all duns will have all of the markings,

and non-duns can have some of them. Any

color can have a dorsal stripe (believed to be caused by sooty or

countershading) but a non-dun dorsal stripe has a different "look"

and "character" to it than a dun dorsal stripe. It certainly can take some experience to tell

then apart, though, and not all horses "follow the rules", so it's

nice that there is now a test to tell dun from non-dun in those confusing

cases. In the days when both true duns

and buckskins were called “dun”, it was not uncommon to see the term

“line-backed dun” used to refer to duns, with dorsal stripes.

The gene is one of the most recent

to be found. There was a test for

“markers” for it starting in 2008, which means they have almost narrowed it

down but not quite. This test is

available through U.C. Davis. In 2014 it

was announced by Animal Genetics that they had found the causative mutation for

the Dun gene, and they offer a test for it now.

They have not published this information though, so some are not

completely convinced. Time will tell.

Duns of all shades do not generally

get dapples like the kind that appear on other colors. It is quite rare to find a dun with dapples (and

most of those that do have them are both Cream and Dun). Duns, like champagnes, sometimes get

"reverse dapples" -- darker spots rather than lighter ones, but these

are not overly common either. Duns also,

like champagnes, do not show "sooty" tones which are common on

cream-dilutes and nondilutes. The theory is that since the gene dilutes

both black and red pigments, the black "sootiness", if present, would

be diluted enough that it would not stand out visually. Although dun shades, like any color, can

range from light to dark, the dilution cannot be "hidden" by black

hair the way a cream-dilute can.

Not all breeds have the Dun

gene. Some of the most common breeds do

not have dun, most notably the Thoroughbred and Arabian, and most

Warmbloods. Even in breeds where it

occurs, it is not a very common color.

Many of the American breeds do carry dun, including the QH and

derivative breeds (Paint, Appy, POA),

the Mustang, and most of the gaited breeds (TWH, MFT, Paso) although it is very

rare in those. Note that in many breeds

it is quite common to call buckskins "dun" and therefore you should

never presume a horse registered as dun is actually dun, especially in British

breeds (i.e. Connemara, Welsh, TB). The

only drafter breed known to come in dun is the Mulassier.

How it works

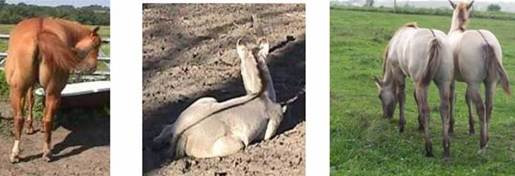

Dun on a chestnut base color is

called Red Dun. In times past it was

also called “Copper”, and the lightest shades of red dun are often called “Claybank” in some places.

They can range from a distinctive

light peachy or apricot tone to a darker shade that could pass for a sunbleached or bodyclipped

chestnut at first glance. The points are

left undiluted, so are whatever shade of red the horse would have

been if it didn't have the Dun gene. The

dun-factor markings are also red.

Typical

chestnut/sorrel: e/e, any agouti, d/d

Dun

on chestnut – Red Dun: e/e, any agouti,

D/_

Dun on a bay base color is most

often just called Dun, but also Bay Dun, Zebra Dun, Yellow Dun, and sometimes

less common terms like "peanut-butter dun" (a pretty accurate

description of the typical body color) and "buckskin dun" (meaning a

dun that looks like a buckskin; not a genetically correct term -- if taken

literally, that term would mean a horse with both a Cream gene and a Dun gene).

They look similar to a buckskin, with yellowish bodies and black points. But the body tone generally tends to be more

"flat" or "earth-toned" and less golden than a buckskin. Since

both colors can have a wide range of shades, the best way to tell them apart is

to look for the dun-markings. Although a buckskin may have a dorsal stripe, strong leg barring is

diagnostic of dun. (In cases where there

is still some doubt, genetic testing can now sort out the buckskins, duns, and dunskins.) The dun-factor

markings on a bay dun will be whatever color the hair would have been in that

place without any dilution -- typically a dark red for the dorsal stripe and

any wither/neck stripes/shadows, and leg barring that is dark red higher up the

leg and black closer to the knees/hocks.

Typical

bay: E/_, A/_, d/d

Dun

on bay – Dun or Bay Dun: E/_, A/_, D/_

Dun on a black base color is

usually called Grulla (the Spanish word for Crane,

pronounced “grew-ya”), sometimes spelled Grullo, or in some places, Black Dun, Mouse Dun, or Blue

Dun. Some breeders call an exceptionally

light, silvery-toned one a “silver grulla”, but this

is not genetically correct (there is a separate gene named Silver, so it should

not be used as a descriptive term).

They have a greyish body color, but

unlike a grey, which when examined closely is a mixture of dark and white

hairs, a grulla's hairs are all the same greyish

color. It can tend toward a tannish

shade in some horses but is usually a "cool" tone tending more toward

bluish. A sunbleached

smoky black can do a very good grulla imitation, but

they are usually more yellowish in tone.

The grulla's dun-factor markings will be

black.

Typical

black: E/_, a/a, d/d

Dun

on black - Grulla:

E/_,

a/a, D/_

Dun on a seal brown base color does

not have a specific official name (and is not recognized as a separate color by

any registry), but is generally called Brown Dun or sometimes Seal Dun by those

who have one. The ones on a darker base

shade would look like a grulla with the tan muzzle of

a seal brown, but would most likely be registered as grulla. The ones on a lighter base shade would look

like a darker shade of bay dun, and these have been called "Lobo Dun"

or “Olive Dun” in some places. In the

past these would have been hard to identify, but now that there is a test for

Seal Brown, they can be distinguished from other duns. We do not have a picture of a confirmed brown

dun at this time.

Breeding for these colors

With a simple dominant gene, it can

be easy to get the color on your foal – just find a horse that is homozygous

for Dun. Breeding such a horse to a

non-dun would give you a heterozygous Dun foal every time:

Punnett

Square example:

|

|

D |

D |

|

d |

D/d |

D/d |

|

d |

D/d |

D/d |

Breeding a heterozygous Dun horse

to a non-dun would give you a 50-50 chance of a Dun foal:

Punnett

Square example:

|

|

D |

d |

|

d |

D/d |

d/d |

|

d |

D/d |

d/d |

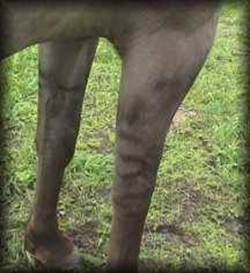

Some close-ups of the “dun-factor” markings

(Photos

provided courtesy of Cedar Ridge QH www.grullablue.com )

Dorsal

stripe:

Leg

barring:

Ear

barring/tips:

Face

mask:

Mottling

on the forearm:

Neck

striping:

Mane

& tail frosting:

Cobwebbing:

Barbs

(or fishboning) off the dorsal stripe:

The

Champagne gene

Like Dun, Champagne is a simple

dominant gene in the dilution category.

Although for many years it was confused with Cream and Dun dilutes, it

has been known to be a separate gene for at least a dozen years now. It's well understood at this point, and it's

not particularly difficult to recognize a champagne,

unless the horse has other genes that interfere with being able to see the

color, such as grey, roan, large amounts of white, or combinations of multiple

different dilution genes. In those cases

it can be difficult or impossible to tell, so the test will be useful. Also, the test will identify homozygous

champagnes. It has been observed that

many of the homozygous champagnes are lighter in body color, and have pinker

skin with fewer freckles than usual.

However, the difference is not necessarily great enough to make them

distinctly different looking, and it is not known yet whether this will hold

true in every case.

The mutation that causes the

Champagne gene was found in 2008 by a team at the University of Kentucky. A test is now available from various

labs. You can read the research paper

here:

http://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1000195

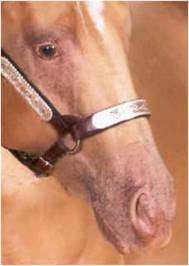

The Champagne gene affects both red

and black pigment equally, lightening red hair to a golden shade (quite similar

to palomino) and black hair to a sort of greyish-to-chocolate tone depending on

the individual. And, unlike most of the

other color-modifying genes, champagne also affects the skin and eye

color. The defining characteristic of

champagnes of all types and shades is pink skin. They are born with bright pink skin and

bright blue eyes. Over time the eyes

usually change to greenish, hazel, amber or light brown. The skin darkens to a more

dusky sort of pink, and develops dark freckles which tend to increase

with age and exposure to sun. Some

horses get so many freckles on their muzzles and around the eyes that their

skin could appear to be dark (especially in pictures), but on closer inspection

the pink underneath the freckles is evident, and looking at the skin on the

sheath or udder, and under the tail, will give a better idea of its true color

without the sun exposure. The pink skin

is a different color than the unpigmented pink skin that occurs under white

markings -- champagnes with pinto markings illustrate that noticeably. If a blaze goes down over the nose, for

example, the outline of the marking can be clearly seen. The white-marking pink skin is brighter pink,

without any freckles (and tends to sunburn), and the champagne skin is slightly

darker pink, with the freckles (and tends not to sunburn).

Champagnes of all shades do not

generally get dapples like the kind that appear on other colors. It would be very, very rare to find a champagne with dapples (and the few that have been seen

are usually both cream and champagne).

They often get what are called "reverse dapples" -- darker

spots rather than lighter ones. Not all

champagnes get them, and they come and go with the seasons. Reverse dapples are not unique to champagnes,

but seen only rarely on other colors.

Champagnes also do not show "sooty" tones which are common on

cream-dilutes and non-dilutes. There may

exist one somewhere, but a "sooty" champagne

has never yet been documented. The

theory is that since the gene dilutes both black and red pigments, the black

"sootiness", if present, would be diluted enough that it would not

stand out visually. Champagnes tend to

have a very even body color, the same shade all over, without the lighter and

darker shading that is common on many other colors. They also often have a metallic sheen to

their coats. Not all champagnes have

this, and plenty of non-champagnes have it too, so it's not a defining characteristic

of the color, but it is fairly common, especially in summer coats. Champagnes often have faint dorsal stripes

that come and go, but they are nothing like a true dun dorsal stripe.

One unusual thing about this color

is that foals are usually born much darker than they will end up when mature,

which is the exact opposite of most foal colors. Typically, the foal's color looks like what

it would have been without any dilution gene -- like a bay foal, for example,

with an amber champagne. The combination of a coat that doesn't look

diluted, with the bright-pink skin and blue eyes, is quite striking. Then, when they shed out in a few months,

they lighten up to their normal adult champagne color. It can be quite a dramatic change. The interesting thing is that some foals are

born already diluted, and don't change much when they shed. It's not as common, but it does happen, and

nobody knows yet why.

There is a color registry for

champagnes, the ICHR, founded in 2000.

They have a very informative website at http://www.ichregistry.com/ which is highly recommended to anyone wanting

to learn more about the color. You can

see pictures of all the registered horses, which display a tremendous variety

of colors and shades; and their pedigrees, with the champagne lines

indicated. You can see what breeds have

the color, and which bloodlines are champagne.

There are also close-ups of all the champagne characteristics, which is

helpful in identifying them when you come across one. Not all breeds have the Champagne gene. Some of the most common breeds do not have

it, such as the Thoroughbred, Arabian, and Morgan. Even in breeds where it occurs, it is not a

very common color. It can be hard to

know for sure, since they have historically (and usually even today) been

registered as something else, i.e, palomino or

dun. It is known to exist today in the

American gaited breeds such as ASB, TWH, MFT, and so on; the stock type breeds such as the

Quarter Horse, Paint, Appaloosa, and so on;

in Minis and grade ponies; in the American Cream Draft; and it has been

introduced to a few Warmblood breeds via those that allow some outside blood

(typically a small amount of QH or Saddlebred).

How it works

Champagne on a chestnut base color

is called Gold Champagne, or just Gold.

They look very much like palominos with golden bodies and white manes

and tails. Occasionally the mane and

tail are not white, but the same shade as the body (this is commonly called a

"self gold") or even somewhat darker.

The body color ranges from light gold to dark gold, but they don't have

the same extreme shade range as palominos do.

Typically they have been registered as palomino or "golden",

depending on breed, but some have been registered as sorrel (presumably they

were registered before the foal-coat shed out).

The ones with darker manes and tails were probably thought to be red

dun.

Typical

chestnut/sorrel: e/e, any agouti, ch/ch

Champagne

on chestnut - Gold champagne: e/e, any

agouti, Ch/_

Champagne on a bay base color is

called Amber Champagne, or just Amber.

They look similar to a buckskin or dun at first

glance, with golden bodies and dark points.

The mane and tail are usually not black, but a dark bronze to chocolate

sort of shade. The legs may be darker

from the knees and hocks down (although not truly black) but often they are not

much darker than the body. Manes and

tails often have "frosting", or lighter hairs along the outer

edges. They are typically registered as

buckskin or dun.

Typical

bay: E/_, A/_, ch/ch

Champagne

on bay – Amber champagne: E/_, A/_, Ch/_

Champagne on a black base color is

called Classic Champagne, or just Classic.

They are the most unusual shade of all.

The color is hard to describe, a sort of greyish brownish, nearly

purplish at times, similar to grulla at other

times. This is probably the color that

was called "lilac dun" by the old-timers. Many have likened it to a Weimaraner

dog. The manes and tails are generally

darker, and the legs may or may not be darker than the body, but there is no

true black hair anywhere. Historically

they have most often been registered as grulla or

dun, but there are many odd examples of classic champagnes being registered as

all kinds of strange colors, including chestnut and brown. It seems that nobody knew quite what to call

them!

Typical

black: E/_, a/a, ch/ch

Champagne

on black – Classic champagne: E/_, a/a,

Ch/_

Champagne on a seal brown base

color is called Sable Champagne, or just Sable.

The darker ones look pretty much the same as a Classic Champagne, and

the lighter ones look like an Amber.

Without testing them to see which agouti genes they have, it can be

impossible to tell them apart. The only

registry to recognize it as a separate color is the ICHR. Most others call them dun, grulla, or buckskin, whichever the registry thinks it most

resembles.

Champagne

on brown – Sable champagne: E/_, At/At

or At/a, Ch/_

Breeding for these colors

With a simple dominant gene, it can

be easy to get the color on your foal – just find a horse that is homozygous

for Champagne. Breeding such a horse to

a non-dilute would give you a heterozygous Champagne foal every time:

Punnett

Square example:

|

|

Ch |

Ch |

|

ch |

Ch/ch |

Ch/ch |

|

ch |

Ch/ch |

Ch/ch |

Breeding a heterozygous Champagne horse

to a non-dilute would give you a 50-50 chance of a Champagne foal:

Punnett Square example:

|

|

Ch |

ch |

|

ch |

Ch/ch |

ch/ch |

|

ch |

Ch/ch |

ch/ch |

Some Close-ups of the Champagne Characteristics

Pictures

provided courtesy of the International Champagne Horse Registry http://www.ichregistry.com/index.htm

Pink

skin with dark freckles:

The skin will be this color everywhere except under pure white markings.

Best

seen on udder/sheath or under tail:

Eye

color: Eye color in Champagnes will vary from an Amber

color to almost a green color – foals are often born with an Aqua or Teal

colored eye which will change to Amber or a green hue as the foal ages.

An Amber eye

A Teal or Green eye

Reverse

dapples:

Champagne with dark dapples

Compare to…………………. Bay

with light dapples

Click

Here To Take Quiz - Duns and Champagnes

![]()

![]()