Bits, Saddle Fitting and Hoof Balance

With

Instructor Eleanor Blazer

Lesson

Two

Saddle Fitting

Girth a horse

tightly so the saddle doesn’t slip.

Wrong!

Position the

saddle correctly so the saddle doesn’t slip.

Right!

Girth the horse “snugly”,

but never tightly.

Tight

girths are just one of the “don’t dos” of tacking up. Horses that are girthed tightly soon become

“cinchy” and dislike being saddled. Once

they resent being saddled, they’ll often reach around and try to bite the

saddler…or they’ll expand their girth area so the girth will be “snug,” but

comfortable when they relax.

That

“snug” girth is nearly always “just about right.” After all, riding is easy….just

keep a leg on each side…and you don’t need a tight girth to do that.

But

before you girth that saddle, let’s study saddles, and then saddle fitting.

Most

of the world calls the “riding” saddle a flat saddle. In the

The

flat or English saddle is split into two basic styles…the Saddle Seat and the

Hunt Seat.

Saddle

Seat riders use a saddle with a relatively flat seat that places the rider well

behind the withers and just behind the horse’s natural balance point

(center.) Saddle Seat riders are

expecting to ride down the road or in the show ring; they are not expecting to

“jump.”

While

any breed can be ridden with the Saddle Seat saddle, the most common breeds are

American Saddlebreds, Morgans, Tennessee Walking Horses, Arabians and most

gaited horses.

Because

the head of the saddle is often cut back to accommodate high withered horses,

the saddles are sometimes called, “cutbacks.”

The

Hunt Seat saddle, often called a Forward Seat saddle, are

very popular now in the

Sub-categories

include: All-Purpose, Close Contact and Dressage.

The

All-Purpose saddle is the most popular due to its general versatility. It has a deeper seat and a padded knee roll

to provide more security and can be ridden in such disciplines as pleasure,

trail riding, horsemanship and even eventing. It is an excellent choice for the new or

novice rider.

The

Close Contact saddle is used for jumping rather than flat work. It is designed with a very flat seat allowing

the rider to maintain a very sharp hip angle facilitating the rider taking the

“two-point” jumping position.

The

Dressage Saddle is used specifically for dressage, giving the rider balance

through the seat while allowing maximum side contact with the horse. The dressage rider wants a straight hip

angle, allowing a “deep” seat. The

straight, longer flap on the dressage saddle promotes a longer stirrup. A knee roll is optional.

The dressage rider’s saddle allows for maximum leg contact.

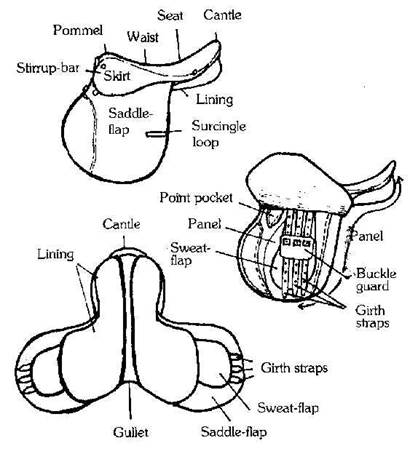

LEARN THE PARTS OF THE FLAT SADDLE

Most English or flat saddle are

made in

The

fittings for a flat saddle—stirrup leathers, stirrup irons and girth--are not

generally included with the saddle, and are selected to meet the needs of the

individual rider.

The

western saddle, originating long before the wild west of the

The

general purpose western saddle is used for everything. But more and more the western rider is

seeking a specialized form, such as the cutting saddle, the roping saddle and

the “games” saddle used for barrel racing and pole bending.

The

cutting saddle has a “wrap around” fork configuration to help hold the rider in

place as the horse moves laterally with almost unbelievable speed.

The

roping saddle has the stirrups set in such a way as to keep them from moving

rearward. This allows the roper to stand

in the stirrups and lean forward without his or her feet swinging toward the

horse’s hindquarters.

The

game saddle is cut small to avoid any kind of interference with the horse’s

movement and to reduce the saddle’s overall weight.

The most

specialized western saddles are the Parade saddle and the show saddle, both

usually sporting silver in an array of patterns. While Parade saddles are big so they can

carry lots of silver, the western show saddle has plenty of silver and a

variety of “seats” to give the rider a “show look.”

LEARN THE PARTS OF THE WESTERN SADDLE

Saddle Blankets and Pads

Saddle

blankets and pads are designed to 1. protect the horse’s back, 2. absorb sweat and

moisture, 3. protect the saddle and 4. help saddles fit better.

NAVAJO

BLANKETS are colorful outer blankets used with the western saddle. They are made of wool and can be quite

expensive. They need to be dry cleaned,

but if cared for, will last a lifetime.

SHEEPSKIN

PADS are sort of the English equivalent of the Navajo blanket. Sheepskin pads are expensive, but if brush

clean after each use and occasionally washed in cool water, they too will last

a lifetime.

BLENDED

FIBER blankets look like Navajos, but are not as durable since then are usually

made of cotton or some synthetic.

IMITATION

SHEEPSKIN is just what it says it is.

Popular because they are less expensive, they don’t hold their shape as

well as the real thing and they are not as absorbent. They are less expensive and are usually

machine washable.

HAIR

PADS are great at absorbing sweat and they

are good shock absorbers. The drawbacks

include being hard to clean and slow drying.

Protective leather pieces (wear patches) under the stirrup leathers on

the western saddle protect the pad, giving it a longer life.

FELT

PADS are available for both western and English saddles, but are hard to keep

clean and cannot be washed.

FOAM

PADS are available for both western and English saddles and are great shock

absorbers. They come in a range of

colors and quality. They have one big

drawback…foam doesn’t breathe, so they create a good deal of sweat and can

setup a situation where the horse’s back is irritated.

THERAPEUTIC

PADS are available in for both western and English saddles. Riders choose them for horses that become

back-sore easily or as an insurance policy when a horse is under extra stress. Before going to a therapeutic pad, check to

make sure the saddle fits correctly.

To know about

saddle fitting, we start with the horse’s back.

Most

veterinarians, horse trainers and riding instructors agree between 25 and 50

per cent of all horses have some degree of soreness in their back. You don’t actually hear them complaining

because horses are pretty stoic when it comes to pain, and the manifestation of

the sore back comes in the form of sour expression, poor movement, loss of

condition and resistance to work. (To

make a preliminary test, just run your finger tips

down your horse’s back on both sides of his spine. If the horse flinches or “sinks” he probably

has some sore spots.)

The

horse’s back is much like a human’s. The

back is composed of a chain of bones, through the middle of which runs the

spinal cord and around the outside of which are affixed large, strong muscles

and the ribs. The horse’s spine was

designed to have weight suspended from it, but not to support weight on one

small part atop it.

When you are sitting on a horse, the horse’s spine is

under strain it was not designed to withstand.

Imagine the strain on the horse’s back when we gallop him, bounce on

him, or jump him.

To

make matters worse for the horse, the horse’s spine has very little direct or

lateral flexion. In fact, the spine

normally only bends in fractions of a millimeter. All this talk of “lateral spinal flexion” is

just that—so much talk; lateral flexion of the horse’s spine is virtually

imperceptible. What lateral flexion he

does achieve, he does by softening his body.

Any

injury or stress to the spinal bones can produce inflammation which essentially

is the mildest form of back soreness. Of

course there can also be damage to the muscles, to the spinal cord itself or to

the ribs.

The

two main causes of “ordinary” sore backs are pressure and friction.

Both

are generally caused by poor fitting saddles, saddle pads and saddle blankets. (After poor fitting tack, the second greatest

cause of sore backs is poor riding skill.)

According

to a study by New Mexico State University National Agri-Marketing Club a very

large percentage of riders do not have properly fitting saddles.

The study considered two types of

riders, ropers and barrel racers. The

roping saddle sample showed 41.3 per of the saddles had unacceptable saddle bar

pressure and nearly 27 per cent showed spinal pressure at harmful levels.

Fit problems were far more likely to

occur at the front of the saddle with 93 per cent showing elevated pressure

points at the pommel.

Bridging was an issue with almost 85

per cent of the roping saddles.

The barrel saddle sample showed

excessive pressure in the front of the saddle in 49 per cent of the cases with

16 per cent showing spinal pressure.

More than 90 per cent of the barrel saddle showed “bridging.”

The study is a myth buster if you

think saddle pads can correct poor saddle fit.

It is incorrect to think a thicker pad will be more comfortable for your

horse. The study revealed that every inch of pad thickness increased the chance

of poor fit by more than 23 per cent because the “pad paradox” increased the

incidence of bridging.

The first time a saddle is placed

on a horse, that saddle should be tested for fit. If the saddle doesn’t fit properly……don’t use

it! And claiming it is the only saddle

available is not acceptable. Anyone who

can’t beg, borrow or purchase a saddle that fits his or her horse should not be

riding.

CORRECT SADDLE PLACEMENT

(ENGLISH OR

WESTERN)

Have

the horse standing on level ground.

Ideally,

we want the saddle placed so it rests solidly and level on the horse’s

back. In this position, the rider’s

center of balance will be just behind the horse’s natural balance point at a

standstill. As the horse begins to move,

engaging the hindquarters, his natural balance point (just behind and slightly

above his elbow) will move back and under the rider as the horse begins to

round his back upward. Now the horse,

saddle and rider are in balance.

Place

the saddle pad or blanket over the withers and well forward. Now place the saddle in position, over the

withers and forward.

Slide the saddle and pad backward until they settle into a

natural position, behind the withers and level on the back.

For many, this

saddle position is going to seem too far back.

It is not!

The

gullet of the saddle will be somewhat over the withers, the saddle will be

level (gullet and cantle level) and the back of the saddle will not be pressing

into the loin area. The girth will not

be immediately behind the elbow, but will be several inches behind the elbow.

Check the pad or saddle blanket.

At least two fingers should slide easily between

the withers and the saddle.

Saddle is sitting level on

horse’s back - off the withers, but not into the loin.

Girth is behind elbow. The saddle is in its natural place and not restricting

shoulder movement.

If

the saddle is left too far forward, well over the withers, and the girth is

directly behind the elbow, the movement of the horse’s shoulders will be

restricted. Both stride and lateral

action are adversely affected.

Properly

position, the saddle will not need to be “tightly” girthed. It stays in position naturally and only needs

a “snug” girth to remain there.

Now

in position, the rider should check the pad or saddle blanket and lift it up

into the gullet so that at least two fingers slide easily between the withers

and the saddle.

Problems

arise when the saddle is left propped forward on the horse’s withers, or when

the saddle is pushed too far back and rests on the loin. (Western saddles with large skirts—mucho room

for silver---are usually the saddles that create soreness in the loin area.)

Horses

with wide flat (mutton) withers can suffer discomfort and pain if the saddle

creeps forward toward the neck.

Rubberized or “non-slip” grip pads can help avoid this problem.

When

a saddle is built with a downward slope fore to aft (Saddle Seat, Western

Equitation Seat), the rider is seated behind the horse’s center of balance,

causing unwanted pressure on the horse’s back near the loin.

You

can spot problems from the ground if you just stand back and observe the tacked

horse.

Are

the forks of a western saddle or the pommel of an English saddle sitting higher

than the cantle? Is the saddle too far

forward crowding the shoulders? Do the

bars of the saddle rest on the loins? Do

the stirrups hang off the vertical?

If

the answer to any of those questions is “yes,” evaluate the design of the saddle;

reposition the saddle and then decide if it is the saddle or just the way the

horse was tacked.

The

tongue on a western girth should not be left unused. The protruding piece of steel could cause

injury if the horse should fall or brush against something solid. If you've got it, use it. If you prefer to tie the latigo, use a girth

with "tongue less" hardware.

Secure the tongue

Do not let the tongue protrude

A

The

bars of a western saddle are usually called Quarter Horse bars or Arabian

bars—essentially, they are the same thing.

A

semi-QH bar is for a narrow to average sized horse with relatively high

withers.

QH

bars are for an average size to wider horse with an average withers for his

size and shape.

Full

QH bars are for a wide horse to a small draft type with a flat withers.

You

should be able to put 3 to 4 fingers together and place them vertically between

the withers and the pommel of the new saddle.

Once a saddle is broken-in, the distance will shrink to

Looking

at the saddle from the back—yes, you need to stand directly behind the horse,

so be careful—there should be no obvious gaps along the back of the saddle.

There

should be space between the end of the saddle skirt and the horse’s hips so the

hip and loin are not rubbed.

You

will need to ride a saddle to make a final determination as to its proper fit.

Ride

the western saddle for 5 minutes and then get off and check the fit again. Has the saddle shifted? Is it rubbing the horse anywhere? Are the withers free from pressure?

Remount

and walk, jog and lope for 15 minutes or more to be sure the horse is creating

a sweat under the saddle pad or blanket.

While riding, you should be looking for unusual behavior…such as laying

back of the ears, bucking, or turning to bite at your leg—all signs the saddle

might not be too comfortable.

When

you are sure the horse has had enough work to break a sweat under the saddle

pad and blanket, return to the barn and pull the saddle. What to you see?

If

the horse’s back has a nice even wet spot showing that the saddle and pad sat

evenly on the horse’s back, you can be pretty sure the saddle is a good fit.

If

there are dry spots, you can be pretty sure the saddle does not rest evenly

along the horse’s back. You might need a

different tree width, or the saddle might not be well constructed, or you may

have had the saddle too far forward or too far back. You’ll have to make some decisions at this

point; retest or find a new saddle.

Saddles,

inexpensive or high priced may have defects such as panel and flaps

asymmetrical, or twisted trees. Be sure

to check the saddle from side to side; some minor differences can be tolerated,

but those can be seen with the naked eye will usually cause pressure point

problems.

Everything

seems to be going high-tech, including saddle fit. There are supposedly computerized saddle pads

with pressure sensors that are placed under the saddle, and then connected to a

computer. The horse is lunged and the

sensors show high or low pressure points on the computer screen.

While

technology is often useful, it is also often complicated, confusing and

useless. What technology is “reporting”

during a single test today, may be far from the truth tomorrow. There are ever-changing variables—the horse,

the saddle and the rider.

A

Place

the saddle slightly forward on the horse’s withers, and then press down on the

pummel and slide the saddle reward until it stops at the place dictated by the

horse’s conformation. Repeat this

placement several times until you are sure the saddle is stopping in the same

place each time. This spot should be 2

to 3 inches behind the shoulder blade.

Lift

the flap of the saddle and find the angle of the points, located just under the

stirrup bars—one on each side. If the

angle of the points is too narrow, the points will dig into the horse’s muscle. If they are too wide, the saddle will sit

down in front putting pressure on the withers. Some points are virtually

hidden. If that is the case, you’ll have

to rely on the panel pressure procedure to make a determination.

To

perform the panel pressure procedure, place a hand on the center of the saddle

seat and press the saddle down on the horse’s back. Hold the saddle in place with one hand while

you run the other hand, palm up, under the panels all the way to the back of

the saddle to feel for any uneven contact with the horse’s back. Lift the flaps and examine to fit to ensure

the panels are snug and even on both sides of the withers, that there is no

pressure on the withers and that there is no “bridging,” space where the saddle

does not make good contact with the back.

In

a saddle with a deep or moderate seat, the cantle should be 2 to 3 inches

higher than the pommel. In shallow

seats, such as close contact saddles, the cantle may be only 1 to 2 inches

higher than the pommel.

If

the cantle is level with or below the pommel, the saddle does not fit properly.

The

area of the deepest part of the saddle seat should be level, placing the rider

squarely on the seat bones and in balance.

The

clearance between the pommel and the withers should be approximately 2 to 3

fingers. If the pommel is higher than

that, then the saddle tree is probably too narrow. If the pommel is less than 2 fingers above

the withers, then the tree is probably too wide. If the panels are stuffed with wool, make

allowance for the saddle to settle about a half inch.

Check

the channel clearance. There should be

adequate clearance over the spine and connective tissue throughout the channel.

The

saddle should not shift excessively side to side or up and down. Some shifting may be due to the muscle

conformation of the horse.

A

saddle should never extend beyond the vertebrae corresponding to the last rib,

as that area is weakest area of the back.

Finally,

monitor the horse’s response to all that you are doing. Watch for body language telling you the

saddle may not be as comfortable as you had hoped. And as with the western saddle, ride the

horse and watch him carefully during movement.

Does he feel or appear free, or do you feel and or see resistance? Observation of the horse in movement may be

the most important element of saddle fitting.

Once

the saddle fits the horse, does the rider fit the saddle?

The

most common fault is having a seat too small for the rider, forcing him or her

to sit at the back of the saddle. In an

English saddle the rider’s knee should be at the center of the position of a

knee roll when the back of the rider’s heel would be on a vertical line dropped

from the center of the rider’s shoulder.

English

saddle sizes range from 16 to 18 inches for adults and from 12 to 16 inches for

children. An English saddle is measured

from the saddle nail (a rivet on the front side of the skirt near the pommel)

to the mid-point of the cantle.

Sit

in the saddle several times before you decide if you fit it and it fits you.

Western

saddles generally have seats measuring 13 to 17 inches. Measure from the fork just below the saddle

horn to the highest upward curve of the cantle.

As a general rule there should be a tiny space between your lower

back/buttocks and the cantle. Don’t be

wedged into the saddle, and don’t have any overhang.

Even

when saddles fit correctly, horse’s get sore backs. One of the causes is putting too much weight

on too young a horse. Riding a young

horse for short periods of time and with discretion helps to strengthen the

horse’s muscular and skeletal systems.

Indiscriminate

and excessive work forced on a horse by large riders quickly results in

physical damage.

Spine

supplying exercises, such as light lunge line work, can help alleviate some

back soreness.

If, during your review of the saddle positioning, you notice your horse

is smiling and appears “ready to go,” he is….so snug that girth and enjoy the

ride.

Assignment:

1.

Make a video of you going over the parts of a saddle, which you have memorized.

Do not use a diagram or other form of assistance when making the video. You can use an English or western saddle.

2.

Tell me about the saddle. Is this the

saddle you normally use? For what

discipline do you use it? What size is the seat?

3. Send me pictures of your horse saddled, with

the girth/cinch fastened. Include one

from each side.

Please

send the video, pictures and report to Ms. Eleanor at: elblazer@horsecoursesonline.com