Bits, Saddle Fitting and Hoof Balance

With

Eleanor Blazer

Lesson One

Bits—Simple, Yet Effective!

Believe me, bits are simple.

There are only two kinds. (There are

plenty of variations.)

Neither kind can work miracles. They

can, however, be effective communicators.

Both kinds can be used to inflict

pain, which is primarily what bits are designed to do. Most advertisements

today attempt to convince possible buyers their special bit will solve training

problems and never cause the horse discomfort. Impossible! Bits don’t solve

training problems. And while they may not be causing discomfort, the best they

can do is be comfortable.

A bit should be used to communicate

with your partner. The very best a bit can do is tell your partner what body

position you want (your partner then knows the gait and pace desired) and which

direction you desire to go.

Understood and used properly bits are

an important aid in getting high performance from your horse.

Unfortunately most bits are not used

properly.

Ask most horsemen and you’ll be

surprised to discover few know much about bits. Few can give an accurate

definition of either kind of bit. And worst of all, few know how the bit they

are using actually works.

A lot of this confusion is created by

bit makers and tack sellers who themselves do not seem to know much about bits.

Catalogs and bit descriptions supplied

by bit makers consistently incorrectly label curb bits as snaffles.

I consider a snaffle a bit. (Many say

a snaffle is a snaffle and a curb is a bit.)

I consider a curb a bit.

And that is it.

There is a snaffle and there is a

curb. What’s the difference?

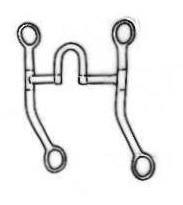

A snaffle has the reins attached opposite

the mouthpiece and has no curb action and no poll action. The snaffle is a direct action bit, meaning

if one pound of pressure is applied to a rein, one pound of pressure is applied

to the horse’s mouth.

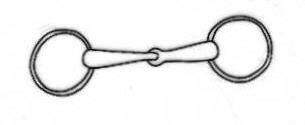

Ring

Snaffle

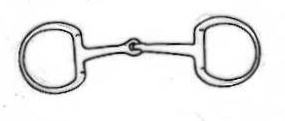

D

Snaffle with Medium Mouthpiece

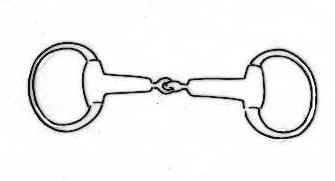

Egg

Butt Snaffle with Thick Mouthpiece

A curb has both curb and poll action

and has the reins attached below the mouthpiece so the

principle of the lever and fulcrum is in effect. That means if the cheek piece of the bit is

one inch and the shank is three inches, the bit is 1 to 3 in leverage. If the rider applies one pound of pressure to

the reins, three pounds of pressure is applied to the horse’s mouth.

Train “uneducated” horses with direct

action (snaffle). Train “advanced”

horses with lever action (curb). With

lever action the rider can be very, very gentle with the reins and still get

plenty of pressure so the horse will easily understand the request.

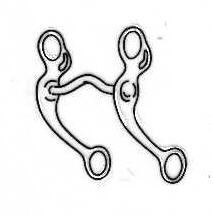

"Grazing"

Shank on

I did not mention the type of

mouthpiece in either bit. That is because the type of mouthpiece does not

define the bit. (You constantly hear that a snaffle is a bit with a jointed

mouthpiece. Not true. A snaffle may have any type of mouthpiece you desire.)

A snaffle—with any kind of

mouthpiece—requires the use of two hands on the reins in order for it to

function efficiently. The snaffle is a direct pressure bit. While the rider

holds one rein steady, the other rein is tugged, thus causing the mouthpiece to

press against the bar and lips of the mouth on one side. The bit pressure

causes discomfort—a communication—and the horse yields in order to avoid the

irritation, thus complying through nonresistance.

You can come up the all the humane

sounding jabberwacky you want, but the truth is the

truth. Bits function on the theory the horse complies with the request to avoid

pain.

The snaffle is appropriate for the

uneducated horse because it allows the rider to literally “place” the horse’s

head in the desired position. Using

direct action pressure, the rider can position the horse’s head, and then while

holding the head position, can influence the horse’s body position with weight

and leg aids.

The snaffle’s direct action can be

used repeatedly within minutes to reaffirm the rider’s desire for a specific

head position and body frame.

The curb bit is a lever action bit.

The shanks of a curb bit (the lever) move around the fulcrum (mouthpiece) and

create pressure in the chin groove and at the poll. In addition, depending on

the mouthpiece, pressures are applied to the tongue, the bars, the lips and

possibly the roof of the mouth.

As a horse advances in his education,

he is generally asked to work on a curb bit.

The lever action of the curb bit magnifies the subtle movement of the

reins as the rider “asks” for head and body frame rather than using bit

pressure to place the horse in frame.

The curb is appropriate for the

advanced horse that understands the cue request and will respond to the

smallest of rein actions

Riders can use a hand on each rein, or

use only one hand when riding with a curb bit.

How Bits Are Used

A snaffle is a direct

action bit (one pound of pressure on the reins equals one pound of pressure on

the bit), and is generally mild because the mouthpiece is usually smooth and

relatively wide in diameter.

A snaffle can be made a

little more severe to encourage a little quicker response by changing the size

(narrow) and style (twisted wire) of mouthpiece.

A snaffle allows the

rider to physically put the horse in the frame the rider desires. The rider tugs on the rein to tip the horse’s

nose into position, or holds the position by leg pressure, pushing the horse

into the bit.

Use a direct action bit

to “place” the horse into the body position desired.

As the horse learns, it

takes less and less time and less and less “placement” of the horse to get the

position desired. The horse is learning

to respond to the request, but it still takes one pound of pressure on the rein

to get one pound of pressure on the mouthpiece.

When the horse is

responding quickly and correctly to the direct action bit pressure (which is

always followed by an immediate release of pressure) the horse is ready to

begin using a curb bit.

The curb is a lever

action bit; one ounce of pressure on the reins will equal 3 or 4 or 5 ounces of

pressure on the mouth, depending on the length of shank and cheek piece. If the cheek piece is one inch and the shank

is 3 inches, then the bit is 3 to 1 in pressure applied.

With a curb, the rider

asks the horse with a very small amount of pressure on the rein. (That means you can just move your fingers

and get enough pressure in the mouth to get a quick response.) The response you seek is the horse taking the

requested position—he knows what to do now and he doesn’t need to be “placed,”

he just needs to be asked.

Use the curb not to

apply more pressure to the horse’s mouth, but to apply less.

Use the curb on a horse

that knows what to do…knows the positions and has learned the correct responses, and understands that by responding correctly

he’ll be left in a comfortable position.

That is the way bits are

to be used. They are always incorrectly used when they are inflicting pain to

“force compliance” rather than teach or ask for a specific response.

All the names given to curb bits—such

as

Ornate

Spanish Style Shank

Bits were invented about 1,000 B.C.,

starting out as a thong through the mouth or around the lower jaw. The idea was

to inflict enough pain that the horse would comply with the handler’s desire

rather than put up with continued discomfort. (Keep in mind men had already

been riding astride for nearly 3,000 years without the use of bits.)

As technology advanced, bits became

much more severe and painful, especially with the advent of the martingale

which allowed horsemen to apply great downward pressure to mouthpieces which

were discs, spikes and chains. The Greeks were using such torture devices as

well as a version of the modern roller bit, as long ago as 500 B.C.

It is interesting to note that not

much has changed in bits or the way we use them since that time. As soon as someone

devised a different bit style, with more or less painful possibilities,

horsemen rushed to employ it. It’s the same today. Horsemen seem to love the

idea of a bit of any kind which will solve their particular training problem.

Seldom, unfortunately does the horseman actually take the time to understand

the bit he or she is using.

"I was told it was mild. I was

told it is a good training bit. I was told a jointed mouthpiece is an easy

bit." Too many horsemen accept what they are told as an excuse not to

educate themselves. And so they take the so called "cowboy snaffle",

which you now know is a curb, and quickly inflict great pain to their horse.

Mechanical hackamores ought to be used on the dude who puts one on his

horse—they can be extreme pain producers, as can the Tom Thumb (a curb) which

has a nutcracker action due to the jointed mouthpiece and lack of spacer bar

between the shanks.

Jointed

Mouthpiece Curb – often ‘incorrectly’ labeled a snaffle

But

then, you can’t blame the bit.

Bits were designed to create discomfort,

and I understand that, and I employ the principle that the horse will, when he

understands the communication, comply to avoid pain.

I also understand and endorse the fact

that it is the horseman, not the bit, who inflicts the pain on purpose, then

continues to abuse the horse with continued and/or greater pressure.

Xenophon, the first to write a

complete book on horsemanship, recognized what he was using—spikes, discs and

chains in the mouth—and how they should be used.

According to Xenophon, the key to the

horse’s acceptance of the bit is the "light hand."

Xenophon’s observation was made 400

B.C. and was as true then as it is today: it is not so much how severe the bit,

but how light the hand.

And a hand is light when it applies

minimal pressure to communicate a desire, and that pressure is momentary,

followed by an immediate release of the pressure.

All bits, and all communication should

be employed in the same manner: light pressure to ask for a response, then an

immediate release of pressure. If the desired response is not forthcoming from

the horse, the request is made again, followed by an immediate release. The

request is repeated until the horse responds correctly, at which time he should

be praised for his action. That is communication, which is horse training.

Heavier, more severe bits may be

employed by the light handed rider when, and only when, they can deliver the

request in a more subtle manner.

Bits can, of course, HELP establish

the horse’s head position—snaffles raising the head, curbs lowering the head.

The bit HELPS by acting as a barrier to establish a frame for the horse. The

rider sets the head by establishing a barrier, then pushing the horse into the

frame by the use of strong legs.

All action initiates in the

hindquarters. Great riders control the hindquarters, pushing a horse to a bit,

never pulling the bit back to force a horse into the desired position.

Heavy curb bits with large or

elaborate (spade, for example) mouthpieces encourage a horse to hold his head

in a vertical position. If the horse puts his head in the vertical, then the

bit hangs from the headstall and does not apply pressure inside the horse’s

mouth. If the horse holds the bit with his mouth while maintaining a vertical

head set, the bit is most comfortable.

The more severe a bit, the more

carefully and gently it must be used.

Here are 2 rather complicated, but

effective ways to rate the mildness or severity of bits.

1. SNAFFLE

Answer

the following questions and give points for each answer as indicated:

l. How many pieces are in the horse’s

mouth?

A. one to 3 pieces equals 1

point.

B. more than 3 pieces equals

5 points.

2.

What is the texture of the mouthpiece?

A. sharp (triangular or edged)

equals 10 points.

B. twisted wire or chain

equals 10 points.

C. twisted metal equals 5

points.

D. wrapped with smooth wire

equals 3 points.

E. smooth equals 1 point.

3.

What is the shape of the cheek piece?

A. round (ring or circle)

equals 1 point.

B. other shapes (eggbutt, D,

etc.) equals 2 points.

4.

How thick is the mouthpiece?

A. ½ inch or more equals 1

point.

B. 3/8th inch

equals 3 points.

C. less than 3/8ths inch

equals 10 points.

5.

Is it a gag or elevator bit?

A. yes equals 8 points.

B. no equals 0 points.

6.

How is the cheek piece attached to the mouthpiece?

A. through holes in the

mouthpiece equals 1 point.

B. all other attachments

equals 3 points.

7.

Are there keys or crickets on the mouthpiece?

A. yes equals 3 points.

B. no equals 0 points.

8.

Is the mouthpiece copper, sweet iron, or does it have copper added to

it,

such as rings?

A. yes equals 3 points.

B. no equals 0 points.

The

most common snaffle you see is a ring snaffle with stainless steel 3/8th

inch mouthpiece. Let’s rate it using

this formula.

Add

points for question one and two together, then multiply points for question

three times the points for question four, and add that total to the previous

total. Add the points for question five

and then subtract the points for questions six, seven and eight. Here is how it rates: Q 1 equals 1, plus Q 2

equals 1 for a total of 2. Question 3

equals 1 point multiplied by Q 4 with 3 points results in 3 points added to the

previous total of 2 equals 5 points. Now

add 0 points for a no answer to question 5 and subtract 1 point for Q 6,

leaving a total of 4 points. Subtract 0

points for Q 7 and 0 points for Q 8 and the final answer is 4 points.

Using

this formula, bits are mild with 5 or less points, moderate with 6 to 19 points

and severe with 20 more points.

2.

CURB

To rate a curb bit, answer the following questions and assign points as

indicated.

1.

How many pieces are there in the horse’s mouth?

A. one to 3 equals 1 point.

B. more than 3 pieces equals

5 points.

2.

What is the size, height and shape of port?

A. no port and/or a joined mouthpiece

skip questions 2 and question

3 and go to question 4.

B. high narrow port and the

port meets the cross piece squarely

equals 10 points.

C. high wide port and the

port meets the cross piece in a rounded

position equals 5

points.

D. medium or low wide port

equals 1 point.

E. unbroken arched mouthpiece

equals 2 points.

F. straight unbroken

mouthpiece equals 3 points.

3.

How is the port angled with respect to the bit’s shanks?

A. port slopes back more than

the shanks equals 1 point.

B. port is parallel to the

shanks equals 1 point.

C. port slopes forward more

than the shanks equals 10 points.

4.

How does the mouthpiece slope side to side?

A. jointed mouthpiece with a

spacer bar to keep the shanks apart

equals 1 point.

B. jointed mouthpiece with no

spacer bar, shanks can move toward

the center under the jaw

equals 10 points.

C. solid mouthpiece which is

perpendicular to shanks equals 1 point.

D. solid mouthpiece, which

slopes down to the shanks, equals 10

points.

5.

How are the shanks bent?

A. they are straight equals 3

points.

B. swept back toward horse’s

chest equals 1 point.

C. are angled forward of

mouthpiece equals 5 points.

6.

How long are the shanks?

A. 1 inch or less equals 1

point.

B. more than 1 inch up to 3

inches equals 2 points.

C. over 3 and up to 4 inches

equals 4 points.

D. more than 4 inches equals

7 points.

7.

What is the texture or shape of mouthpiece?

A. sharp (triangular or

edged) equals 10 points.

B. twisted wire or chain

equals 10 points.

C. twisted metal equals 5

points

D. wrapped with smooth wire

equals 3 points.

E. smooth equals 1 point.

8.

How thick is the mouthpiece?

A. ½ inch or more 2 points.

B. less than ½ inch equals 3

points.

9.

Where does the curb strap attach?

A. same ring as the bridle

cheeks equals 0 points.

B. separate ring below ring

for bridle equals 2 points.

C. separate ring behind the

ring for bridle equals 5 points

10.

How are the shanks attached?

A. through holes in the

mouthpiece as most Pelhams equals 1 point.

B. all others including

welded solid equals 3 points.

11.

Are there keys, crickets or a roller on the mouthpiece?

A. yes equals 3 points.

B. no equals 0 points.

12.

Is the mouthpiece copper or sweet iron…or does it have copper or iron

added to it in any way?

A. yes equals 3 points.

B. no equals 0 points.

To

rate the severity of the curb bit use this formula:

add the points together for questions 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. Now add the points for 6 and 7 together and

multiply by the points for question 8.

Add that to the previous total and then subtract the points for

questions, 9, 10, 11 and 12.

Let’s

rate the most standard curb seen today.

This bit is solid jawed, has a low port with a 5 inch shank and is made

of stainless steel. The curb strap

attaches in the same ring as the bridle.

Here is the rating: Q 1 equals 1 point, Q 2 equals 1 point, Q 3 equals 1

point, Q 4 equals 1 point, Q 5 equals 3 points for a total of 7 points. Now add the points for question six (7) and question seven (1) for 8 points and

multiply the points for Q 8 which is 2 points for a total of 16 points. Add the 16 points and the 7 points for a

total of 23 points, then subtract 0 points for question 9, and subtract 3

points for question 10, for a total of 20, then subtract 0 points for question

11 and 0 points for question 12. The

total then is 20 points.

The

rating then for the most common (and cheapest) curb bit is 20 which makes it a

severe bit for any horse. A score of 6

to 19 points would be a moderate bit and a score of less than 6 would be a mild

bit.

Never get a bigger, stronger bit to

control a horse. That is a sure sign of a poor horseman.

Before any bit is selected, the

knowledgeable trainer or rider will determine the configuration of the horse’s

mouth by observation and measurement.

Does the horse have a deep mouth, short mouth, wide mouth, thick tongue,

long tongue, narrow jaw, etc.?

Determining mouth configuration is the

first step to bit selection.

Whether

curb or snaffle, the correct width of the bit is very important.

To

measure the width of the mouth you can use a piece of twine or a wooden dowel

about 12 inches long. Put the dowel in

the horse’s mouth where the bit would be placed. Mark the dowel or string on each side of the

horse’s mouth to get the correct width for the bit. Always round up. If the width is 4 and 7/8th, then

get a 5 inch bit, not a 4 and ¾ inch.

To

determine if you horse has a lot of tongue or a little, lift his lips when his

mouth is closed. If the horse’s tongue

sticks out over the bars of the mouth, the horse has a thick tongue.

To

determine the room inside the mouth put your index finger in the side of the

horse’s mouth where the bit mouthpiece would go. When the horse stops trying to chew your

finger, bend your finger and see if it hits the roof of his mouth. If you touch the roof of the mouth, the horse

has a low palate.

While determining a horse’s mouth configuration, also check the horse’s

teeth.

A

horse’s teeth are critical to health, longevity, bit acceptance and

training. A horse must eat efficiently

to maintain health, and he must have a comfortable mouth or his attitude and

performance will be adversely affected.

A

horse having trouble with his teeth will often toss his head in response to the

bit, hackamore or halter. (Hackamores

and halters apply pressure to the cheeks, pushing the flesh against sharp edges

of teeth.) A horse with tooth problems

will also carry his head and neck crooked.

The

teeth are divided into “incisors” (front teeth used for biting and tearing) and

“molars” (back teeth used for grinding.)

The

mature horse has 40 teeth, while a mare has 36.

The stallion or gelding has “tushes,” or pointed teeth between the

incisors and molars. Tushes are not

always found in mares.

When

a horse gets his teeth, the size, shape and markings can tell you the

approximate age of the horse.

To tell the age of any horse

Inspect the lower jaw, of course.

The sixth front tooth the tale will tell

And every doubt and fear dispel.

Two middle "nippers" you behold

Before the colt is two weeks old

Before eight weeks, two more will come

Eight months, the "corners" cut the

gum

Two outside grooves will disappear

From the middle two in just one year

In two years from the second pair

In three the corners, too, are bare

At two, the middle "nippers" drop

At three, the second pair can't stop

When four years old, the third pair goes

At five, a full new set he shows

The deep black spots will pass from view

At six years, from the middle two

The second pair at seven years

At eight, the spot each "corner"

clears

From the middle "nippers" upper jaw

At nine, the black spots will withdraw

The second pair at ten are white

Eleven finds the "corners" light

Continued-I'm out of characters!

Update: As

time goes on, the horsemen know,

The oval teeth, three-sided grow.

They longer get, project before,

Till twenty, which we know know

more.

"Gleason's Handbook of Horses" published in 1892

Sometimes

horses and mares will develop small, pointed teeth in front of the molars of

the upper jaw. These teeth are known as

“wolf” teeth. They don’t often appear in

the lower jaw, but they can. Wolf teeth

interfere with a bit only when the bit is being used improperly, being pulled

back in the mouth. However, it’s not a

bad idea to have wolf teeth removed (it’s very simple) eliminating the chance a

bit will bump against them.

The

upper jaw is wider than the lower jaw, so when the horse grinds its forage or

grains, the teeth do not create a completely smooth table…the outer edges of

the upper jaw teeth can become sharp, while the inner edges of the lower jaw

teeth may remain ragged. The sharp edges

of the upper teeth can irritate the inside of the horse’s cheek, while the

lower teeth can cut or scrape the horse’s tongue.

To

remove these sharp edges we “float” the horse’s teeth. (Floating is the

“smoothing of the rough edges of tooth by the use of specific file called a

float. Floating is most often done by

hand.)

In

humans, once the permanent teeth come in, growth of the tooth stops…not so with

the horse whose teeth continue to erupt from the gum line throughout his

life. (continuous eruption) Because the teeth are worn down from

the grinding involved in chewing, the teeth continually push up through the jaw

bone to re-level the teeth within the mouth.

Because

the horse has a fixed amount of tooth to erupt, it is extremely important that

“aggressive floating” is avoided. I

advise not allowing anyone to “power float” a horse. Power floats (floats driven by electric

power) frequently take too much off the tooth, actually taking years off the

horse’s life.

On

occasion a horse’s incisors will not meet properly. If the upper teeth stick out in front of the

lower jaw, it is called “parrot mouthed.”

If the lower teeth are in front of the upper incisors, the horse is said

to have an “undershot jaw.”

The

teeth a horse loses include his baby incisors and his baby molars. The baby incisors come out pretty easily, but

often the baby molars hang around for awhile, sitting on top of the incoming

permanent molar. While the baby molar is

sitting on top of the permanent tooth, it is called a “cap.” Caps will fall off on their own (you’ll find

them in the manger); however, you or your veterinarian can remove a stubborn

cap, making the horse’s chewing much more comfortable.

In young horses, about 3 years of age, you’ll

often see a large lump on the bottom of the jaw….this is the base of a fully

developed tooth which will continue to erupt, eventually eliminating the lump

on the lower jaw.

As

a horse grows older, the top of the tooth (crown) wears down, followed by the

neck of the tooth and lastly the root. A

4 year old horse has about half of his tooth protruding from the gum, while an

older horse may have only stubs left.

You

must constantly be alert to the condition of your horse’s mouth. Uneven wear, excessive wear or misalignments

can cause health problems as well as training problems.

Performance

and behavioral problems include tossing of the head, refusal or reluctance to

respond to communication through the reins and bit, and mouth opening. The horse will often carry himself crooked

and out of balance in an attempt to avoid mouth pain.

To

flex at the poll, the horse’s lower jaw must slide forward. If the horse wants to raise his head, the

lower jaw slides back just a small amount.

If the horse has misaligned teeth or rough tooth surfaces, the jaw

cannot slide easily, so the horse will avoid the request or open his mouth to

allow the jaw to move. (Drop your own

chin to your chest while concentrating on your lower jaw…you can actually feel

it move forward. Now roll your head back

and you’ll feel your lower jaw move backward.)

Attempting

to force compliance to requests by using a standing martingale or tie-down or

using a noseband to keep the mouth shut will only increase the problem and

create greater mouth pain.

The

ability to hold a bit without discomfort is critical to any performance horse

being trained to high levels. A painful

mouth can affect a horse’s performance just as any other unsoundness.

If you consider your horse’s mouth,

then selecting a bit is much easier. Usually a large, round, smooth mouthpiece

is going to be mild and comfortable for most horses. However, if your horse has

a small mouth and a thick tongue, then a large mouthpiece is going to be

uncomfortable. A narrow mouthpiece may be toward the more severe, but for this

particular horse will be much better suited.

In

nearly every case, when a horse is fighting a bit or ignoring it, there is a

dental problem or the bit is too severe for the horse. The horse is trying to

avoid the pain being inflicted.

The

thinking, knowledgeable rider will immediately determine the cause of the

behavior. If it is not a mouth problem,

then the rider will return to the use of a milder bit.

MOUTHPIECES

When it comes to mouthpieces, average

diameter, smooth and copper usually combine for the mildest bit.

Ports will help keep the horse from

getting his tongue over the mouthpiece. Rollers and crickets sometimes soothe a

nervous horse.

These mouthpieces can be found in

either a snaffle or a curb.

All other mouthpieces are

questionable. They may be of much more importance to the rider’s ego than to

the benefit of the horse.

The snaffle generally comes as An

"O" (ring), D or egg butt with a jointed mouthpiece. The O forms the

snaffle cheek piece and if allowed to slide through the end of the mouthpiece,

it can pinch the edges of the horse’s lip. It is best to have a sleeve on the

ring, which is the idea of the D. The egg butt also has a sleeve which prevents

pinching.

Young horses do very well on the jointed

mouthpiece snaffle. But they also do well on a snaffle with a small port, or a

curved hollow rubber bar.

When placing the snaffle in the

horse’s mouth you should note the width of the mouthpiece. The bit should be

wide enough not to pinch the horse’s lips inward. The mouthpiece should fit

snugly in the mouth, and may create one wrinkle at the corner of the mouth.

The snaffle may have a chin strap

which attaches below the reins. The chin strap serves no purpose, but some

claim it helps to keep the cheek pieces from being pulled into the mouth. Any

rider who pulls the cheek piece of a snaffle into the horse’s mouth needs to

dismount; he or she is not yet ready to ride a horse.

The most important part of the snaffle

is the one holding the reins.

More highly trained horses on curbs

can be reined with two hands or one hand. The key to the curb is that it

applies pressures in three places, the poll, the chin groove and the mouth, all

at the same time. These pressures are supposed to combine to allow the rider to

give a more subtle cue while giving the horse more information concerning gait,

head set and body position.

The mouthpiece of the curb too should

fit snugly into the corner of the horse’s mouth. The chin strap should be loose

enough to allow you to put two fingers between the chin groove and the strap.

The chin strap should begin to engage

the chin groove when the shank of the bit has moved about 45 degrees.

The chin strap should be slightly

tighter for fast work and slightly looser for slow work. With the chin strap

slightly tighter, the cue will be delivered with less rein action.

The most important part of the curb is

the one holding the reins.

The full bridle is actually two bits,

four reins. The full bridle is a snaffle, often called a Bridoon, and a curb,

both in the horse’s mouth at the same time. The bits are used one at a time in

order to refine or expand the communication being offered.

The material used to make bits is

often very important to the horse. Most horses get along quite well with

stainless steel. At the same time, most horses do not like aluminum. Neither

material stimulates a lot of moisture in the mouth.

Copper stimulates moisture and horses

generally like a full copper mouthpiece, or a mouthpiece with inlaid copper,

copper rings, copper port, or copper roller.

Horses especially like iron bits and

are very delighted by iron with a little rust deterioration, known as sweet

iron. Iron causes a horse to salivate and thus keep the mouth moist and soft.

Plastic or rubber bits generally cause

a horse to have a dry mouth.

Any claim that a bit is going to solve

training problems, reduce resistance, give more comfort, control the rogue or

get the horse to swim on his back while whistling Dixie is bunk.

Bits do what they do, create pressures

in order to deliver messages from the rider.

A good horseman considers his horse

and his education level, selects a bit which he hopes will communicate

effectively, and then he uses the bit in the least abusive way possible.

There is no reason not to change bits if you

think a change will benefit your horse.

It is a good idea to have several

bits to choose from. Horses often like a change of bits as they progress in

their lessons. And every horse is an individual. What works well with one may

not be enjoyed by another.

While bits are simple, communication

is not.

Before blaming a bit for poor

behavior, or seeking a new bit to solve a training problem, rethink your

effectiveness in communicating with your horse.

Finally,

a word about bitless bridles. (What is

said here about bitless bridles can also be said about bosals. We are not talking about a mechanical

hackamore which is a torture device and nothing like a bitless

bridle.)

Lots

of horses like to be ridden in a bitless bridle,

mostly to get away from riders with bad hands.

If

you want to use a bitless bridle, that is fine, as long

as you understand that it also applies pressure in an effort to get the horse

to move away from discomfort and into a position of comfort.

Because

a bitless bridle doesn’t produce much discomfort, a

horse will seldom if ever, learn to carry himself with much collection. A bitless bridle doesn’t provide the needed

barrier to forward movement necessary to create a shortened frame and rounded

back. A horse going on a trail ride

will be perfectly happy in a bitless bridle as he can

remain flat, relaxed and elongated.

Choose

a bitless bridle if you have no intention of asking

for advanced level exercises.

Assignment:

1. Describe the bit you have chosen for

your horse. and then rate it using the formula in the lesson. Please attach a picture of the bit.

2.

What is the age of your horse? Describe your horse’s level of training.

3.

Why did you chose the bit you are using?

4.

Please send a video of you inspecting your horse's mouth. What is the width? Is the palette low or

high? Does the tongue appear to protrude

over the bars? Load the video to YouTube

and send me the link. Make sure the

security setting is "public".

5.

How long since his last dental checkup?

What was done during the appointment?

Send your report to Ms. Eleanor at: elblazer@horsecoursesonline.com

Be sure to include your full name and email address. Please check spelling and write in complete

sentences.