Behavior Modification

By

Dr. Jim and Lynda McCall

Copyright©2003

Lesson

One

EVERY ACTION CAUSES A REACTION

For about 100 years, scientists have been searching for ways to identify

and explain behavior. While we might describe behavior as the way an animal

acts, behind the ivy covered walls of universities, researchers carry this

definition to the "nth" degree.

Behavior is any observable or measurable movement of an organism,

including external and internal movements, and glandular secretions and their

combined effects.

Complicated? You bet. Yet the beauty of science to reduce complicated

systems to simple terms can enable us to explain the whys, whats

and hows of horse behavior. Training horses becomes a

lot clearer and easier when you have a basic understanding of horse behavior

and how to manipulate it.

The foundation of the study of behavior is based upon the fact that all

behavior is influenced by what happens immediately after. To help keep things

simplified, the action or behavior is referred to as the stimulus and what

happens after is called the response.

It

does not manner whether the horse itself, Mother Nature, another animal or a

person provides the response. What does

matter is how the horse feels about the response. Is the response positive or negative to its

well being.

Let's begin by looking at some of the basic instinctive responses of

horses. These behaviors are often called

reflexive behaviors.

A

reflex behavior happens involuntarily when an event causes the horse to

instinctively respond in a given way. For example, a sandstorm triggers the

horse's third eyelid to lower for eye protection. Heat causes horses to sweat

through their skin.

A reflex behavior

happens involuntarily when an event causes the horse to instinctively respond

in a given way.

Reflexive responses like these happen to all members of the equine

family. Most of the time we think of reflexive behaviors as being related to

internal body function of the horse but there are reflex behaviors that must be

dealt with when living with horses.

We

think of fear as being a reflexive response. Fear can be described in terms of

physiological responses. There is a

change in biochemistry of the body that causes some of the body organs

including the brain to act in specific ways.

So anytime you do something that instinctively triggers fear in the

horse, you are creating a reflex behavior.

Most of the time, we try to avoid causing fear in the horse because fear

triggers a horse's flight or fight syndrome.

And, in this mode, horses can be hazardous to humans.

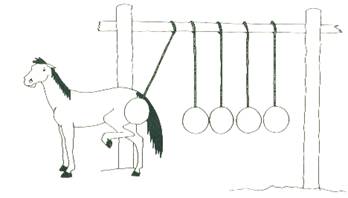

One

of the classic images of creating intense fear in a horse is the old-bronc stomper roping a young horse, tying the frighten

animal down, throwing a saddle on its back and cinching it down. The instinctive response or reflex is for the

horse to try and buck just like it would if a mountain lion jumped on its back.

Kicking can also be a reflex behavior.

A naive horse will often fire out when startled from an unseen threat to

his rear.

This is why horsemen never approach a horse from the rear. A horse cannot see directly behind

itself. And, it is always a good idea to

let a horse know that you are approaching by talking to it or calling its

name. Startling a cat-napping horse may

not be pretty.

Other events that can trigger instinctive

fear in naive horses are:

• Girth pressure

• Stirrups banging on their sides.

• Carrying a bouncing rider on their

back

Not all horses have the same instinctive fear triggers and the outward

expression of the fear may be different between horses. Some horses may run.

Others may buck or collapse.

The bottom line is that you caused a behavior that caused the horse's

body feel fear. How the horse handles his fear will be individual. By understanding the stimuli that can cause

instinctive fear in the horse you are one step closer to learning how to

manipulate its behavior.

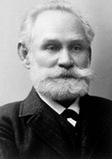

The first recognized step in learning to manipulate reflex behavior was

taken around 1900 by a Russian scientist, Ivan Pavlov, a Russian scientist

trained in biology and medicine. Pavlov

was studying the digestive system of dogs and their relationship between

salivation and digestion. He learned

that when a dog sees food, he begins to salivate which tells his stomach to get

ready to digest feed.

Ivan Pavlov

Like a true scientist, once he learned the normal sequence of events, he

wanted to see if he could manipulate it.

He wanted to make the dogs salivate without presenting food.

Pavlov presented dogs with food along with the sound of a bell. The dogs salivated. After several joint presentations, Pavlov

presented the dogs with only the sound of the bell, the dogs salivated. The learning process of the dogs associating

the sound of the bell with the food was called Conditioning.

Pavlov had conditioned the reflex behavior of salivation. For this he won the Nobel Prize in

Medicine/Physiology in 1904. His experiment laid the foundation for a type of

learning referred to as Classical Conditioning.

Today, Classical Conditioning is recognized as one of the two basic ways

that learning occurs. The other system,

Operant Conditioning, is based upon the principle that every behavior can be

controlled by the event that immediately follows the action. That is, we can control (or condition) a

behavior by what we do after it occurs.

Operant Conditioning is based upon the principle

that behavior can be controlled by the event that immediately follows.

B.F. Skinner is considered the father of Operant Conditioning. In the first half of the twentieth century in

a laboratory at Harvard, Dr. Skinner began studying learning. His research animal - rats. The task to be learned - a wooden maze box

now referred to as a Skinner box.

He

found that he could manipulate the behavior of the rats as they moved through

the maze. If he rewarded the rats for

making a specific turn in the maze, he increased the chance that the rats would

turn that way each time they ran the maze.

Controlling what happens immediately after a behavior influences the

odds of the behavior reoccurring.

Reinforcers can be either postive or negative

but they always strengthen the behavior.

On the other hand, the goal of punishment is to eliminate a specific

behavior.

In

Operant Conditioning, aka horse training, we control the reinforcer. We decide the best way to manipulate the

behavior. We decide which behaviors to

reward and which behaviors should be eliminated.

For example, a horse bites you. If you immediately (immediately

being the operant word here) deliver a response that intimidates the horse, you

decrease the chance that he will bite you again. If you scream, draw back or run away, you

increase the odds that the horse will bite you again. This is an example of

punishment.

It

is time to ask the young 2 year old to trot for the first time. After much urging, he breaks into a few trot

steps. As he is trotting, you praise

him. You are positively rewarding his

behavior. If you wait till he stops

jogging to reward his behavior, you are also positively rewarding his behavior

- but you are rewarding the stop. Not

the trot.

Training horses (and all other animals including humans) falls mostly

under the category of Operant Conditioning.

Consider some well-known quips from various horse trainers.

• "Hit what comes at

you"

• "You can train a horse to

do anything which doesn't cause him

immediate

pain"

• "Horses perform at their

peak, either due to pain or the

suggestion of

pain"

• "Punish the horse for all

the wrong responses. Do nothing when

he does it right and the horse will figure out

how to do it right"

• "Make the wrong thing hard

and the right thing easy"

While we would disagree with the training philosophies behind some of

these statements, the bottom line is that each comment is saying

Manipulating horse behavior is done by creating

either positive or negative consequences for specific behaviors.

By

understanding this simple principle, you have found the road that leads to

becoming a successful horse trainer. The first step down the road is to

understand the things that have the power to change behavior, the reinforcers.