Behavior Modification Techniques

By

Dr. Jim and Lynda McCall

Copyright

© 2003

Lesson Eight

FLOODING

VS DESENSITIZATION

Somewhere in the southwestern

At this point, the cowboy slips a braided hackamore over the horse's

head. He begins to sack out the colt by flipping an old blanket over its

shoulders and back. If the bronc is worth his salt,

dust and dirt will fly some more until it turns to mud as it mixes with the

sweat pouring off both bodies.

The fit begins to die down as the mustang's survival instincts kick in.

With the horse's head tied securely to the post, the horse wrangler, carrying

the saddle, approaches his shoulder.

The bronc fails to submit. With the only part

of body still free to resist, the bronc fires a

couple of well aimed blows with his hind legs. Placing the saddle back down on

the ground, the seasoned bronc-stomper pulls out a

scarf and another rope. The colt has left the horse breaker no choice but to

tie up a hind foot and blindfold the cunning critter.

The blindfold is twisted into the cheekpiece

on either side of the hackamore and slowly slid over the bronc's

eyes. Next the old soft braided rope is looped around the neck and tied with a

bowline knot, leaving about 16 feet of line free to snare a back leg. Another

struggle takes place before the rope can be drawn back through the neck loop

and tied off.

Next the saddle goes on and the cinch is pulled up tight. A lot of fight

has gone out of this previously unrestrained animal. The bronc-stomper,

after unhooking the tie to the post, now earns his name and his pay. He

slithers up into the saddle with the stealth of a rattlesnake stalking a rat

and drops lightly into the depth of the horse's back. He reaches down easy to

loosen the blindfold, then unties the slip knot holding the hind foot off the

ground.

The horse, apparently blinded by the bright overhead sun, stands

quietly. The rider tickles his sides with a light rake of his spurs.

Explosion! It is man's athletic

ability against that of the horse. The spurs rake, the quirt whips the flanks

of the sweat soaked horse. In a few minutes the horse gives up and runs, then

tires to a jog. The day's lesson is over.

The

fight or flight syndrome is still built into most horses born in the

twenty-first century. The bucking, stomping, and squalling is

the horse's reaction to a simulated predator attack.

This method for breaking horses has been around a long time and is

probably responsible for the old horsemen's saying: "There never was a

horse that couldn't be rode and there never was a cowboy that couldn't be throwed."

The truth in these words is founded upon an instinctive fear of horses.

Horses fear being pounced on by creatures that land on their backs. Peaceful

grazing animals are eaten by predators who behave like this. Four thousand

years of domestication has not erased this survival instinct. The

fight-or-flight syndrome is still built into most horses born in the

twenty-first century .The bucking, stomping, and squalling is the horse's

reaction to a simulated predator attack.

Unfortunately, this innate fear is not the only one which plagues

horses. Specific horses may be afraid of sudden movements, loud noises, cars,

trains, sonic booms, or being bound around the heart-girth. The list goes on,

leaving the horse trainer to figure the best way to handle these fears.

Historically there have been two major approaches. The one most folks

think of first is the one described in the opening story - flooding. It works

well on many horses, but it runs a high risk of both physical and mental injury

.This technique starts by identifying what is frightening the horse. Then the

frightening stimulus is applied full strength while preventing the horse from

escaping it. The frightening stimulus is kept up until the horse either dies or

gets used to it.

While effective on some horses, the thrashing and fighting of a

terrified horse can create physical damage to the barn, the horse and the

human. The mental damage suffered by many horses is often just as bad, although

more subtle. They do what we want, but in a mechanical sort of way without any

willingness. Some weaker horses mentally snap and are never quite right

afterwards. Their spirit is completely broken.

There are also some problems if the flooding is not completed. For

instance, when trainers break horses using the flooding techniques used by the

1885 bronc-stomper, it is important for the rider to

stay in the saddle until the horse stopped showing fear. If the horse manages

to throw the rider, flooding is not completed. Instead the horse learned that

fighting can eliminate the cause of his fears. Therefore many trainers today

use flooding only as a last resort, when all else has failed. They also keep in

mind that if you are going to flood, you had better do it properly.

The other approach is slower and requires more patience, but is much

safer since it has a very low risk of physical or mental injury. It is called progressive desensitization by

some and systematic desensitization by others. We call it, simply, desensitization.

As with flooding, desensitizing begins by identifying a specific thing

that a horse fears. Once identified,

the trainer works out a plan whereby the frightening stimulus can be reduced to

a level that does not intimidate the horse.

Now the altered stimulus is presented to the horse. If the trainer was right, the stimulus will

not create any fear in the horse. Slowly

over the course of several training sessions, the intensity of the stimulus is

increased in very small increments.

Done correctly, the horse should calmly accept each new level of

increased intensity. If, at any time,

the horse shows signs of fear it indicates the trainer has advanced too

quickly. The solution is to fall back to a level that the horse can handle, and

continue the process from there.

Desensitizing takes more time, but the benefits are substantial. The

horse does not need to thrash and fight to escape. Consequently, there is far

less chance of physical damage to the barn, the horse or the human. Mentally,

horses find this method less stressful, which preserves the spirit so prized by

horsemen.

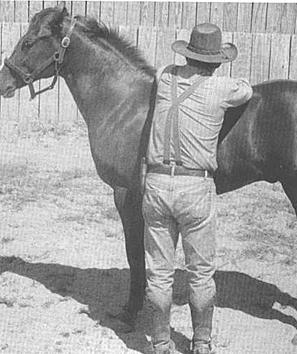

A good example of desensitizing a horse's fear of carrying a rider is

the method we developed which has been called by some “breaking without

force" or "tackless training."

Pressure on the horse's back is applied at a level the horse will accept

without fear. This can be merely a hand placed on his back. The next step would

be two hands. When the horse feels comfortable with that, an arm or two may be

pressed across his back. By continuing in small steps, and never going to the

next step until the horse is comfortable, you will soon be bellied across his

back. Sitting up is only one more small step. The

horse has been desensitized to carrying a human without the thrashing, fighting

and damage so characteristic of the flooding approach.

Applying

pressure on a horse's back at the level he will

accept without fear is a good example of a desensitization technique.

Spooky horses are usually trained best using desensitization training.

Flooding can destroy these sensitive animals. Whatever stimulus causes them to

spook can be decreased and reintroduced at a level they can accept. By

gradually increasing exposure to the fear object these horses will learn to

ignore what previously frightened them. For example, horses with fears of loud

noises, such as thunder, can be desensitized using high quality tape

recordings. The volume can be turned down to an acceptable level, then

gradually raised in stages. One major advantage of tape recordings is that it

allows you to present the fear at opportune moments such as feeding time.

A horse that strongly objects to carrying a sack of rattling cans is a

more common problem for trail riders. The wildest beast can be desensitized by

using this simple technique:

Start by quietly shaking a sack of cans at a distance from the horse

where he shows interest but not fear .Slowly increase the sound to its loudest.

Step in closer and repeat the sequence. If the horse should show fear at any

point decrease the noise level, step back or stop the sound completely. Walk up

to the horse with the sack and let him investigate. Once his curiosity

is satisfied, return to an acceptable location and begin desensitization

again. It won't be long until the horse will no longer be apprehensive about

what it once thought was a "horse eating sack."

Desensitizing also works well on young

horses because they aren't mature enough to handle a great deal of stress. A

young horse has to learn to accept a myriad of new experiences. One difficult

lesson is the horse's acceptance of restraint. Tying a weanling up hard and

fast, either to a wall or a snubbing post, is an example of flooding. The

pressure is relentless and inescapable. He must submit or die. A few die. Some

break legs or pull down their heads. (These horses have dislocated the vertebrae

where their heads join their neck. They will, forever, hold their heads to one

side - thus the term "pulled down head").

A less traumatic approach to teaching restraint exists

using desensitization techniques. By haltering a young foal and leading him

along with his dam, the foal learns restraint in increments. At first the foal

will try to follow his Mom. The new situation, the halter, will inevitably

cause him to pull away. Small amounts of pressure will bring him under control

because he wants to return to his dam. Increasing the time before the foal can

return to his mother's side establishes gradual control without unnecessary

fear.

As you can see, desensitization is a very simple concept. To change

concepts to useful tools for training horses requires an understanding of the

horse. You must be always willing to let the horse tell you how much he can

take and when he has had enough. Without the ability or desire to read a horse,

concepts will always be concepts and the union between horse and man will never

exist.

By

haltering a young foal and leading him along with his dam, the foal learns

restraint in increments.