Role and

Responsibility of Riding Instructor

Lesson Two

Understanding

and selecting equipment is one of the most important factors in having students

experience success during a lesson.

In this

lesson we’ll discuss saddles, the components that make up a saddle, safety and

maintenance of saddles, and correct saddle fit for both horse and rider. We’ll examine saddle pads and their intended

use, as well as how they can cause poor saddle fit. We’ll review the bridle, different types and

uses of bits and types and uses of reins.

We’ll talk about all of the extras:

martingales, draw reins, spurs, crops, helmets, and riding boots.

There are

many different types of saddles. Let’s

review two of the most common: the western saddle and the flat saddle. (In the

USA the flat saddle is commonly referred to as an English saddle.) Both types have unique descriptive terms and

are designed with a different rider position in mind.

The Western Saddle

There is

only one type of western saddle, right?

Wrong! As horsemen and events

have become more specialized, saddles have followed suit. This specialization allows the horse and

rider to perform in different ways and at their absolute best. As we discuss the different types of saddles,

we’ll also investigate variations and styles.

The core

of the saddle is the tree.

The tree

is the solid portion that the saddle is built around. The tree is most commonly made of fiberglass, aluminum or wood covered

in rawhide. The type and shape of the tree determines how it will fit a horse.

The

underneath part of the tree has two main parts: the bars, which are the lateral

or side portions of the tree and the gullet that is the arched portion of the

tree. The degree of “arch” and the width

of the bars determine the fit.

The most

common western tree is a “semi quarter” tree.

This will fit most horses.

For a

horse that is very broad across the withers or mutton withered (flat and wide),

a “full quarter” tree is usually needed.

Small

narrow horses, such as the Arabian, need a narrow tree, commonly known as an

Arab tree.

The top

portion of the tree has four basic parts, these are: the horn, which is what I

recommend holding on to if your horse begins frolicking, the fork or the swell,

which is the top portion of the gullet, the seat, obviously the area where the

rider sits, and the Cantle which is the raised area behind the rider’s seat.

The tree

is only the framework to the saddle. It

is not unbreakable. If a horse rolls

with a saddle on or the saddle receives blunt force trauma it is possible for

the tree to break or crack, rendering the saddle useless. A saddle with a broken tree must never be

used on a horse, as it no longer works as designed and the creation of a very

sore-backed horse is inevitable.

To check

a saddle for a broken tree, place one hand around the horn and the other on the

cantle--try to “fold” the saddle upward.

If there is a lot of movement, there is a good chance the tree has been

broken. If the saddle merely gives

slightly, then the tree is not broken.

The

“skeleton” of the saddle is covered with leather.

The

underneath portion of the saddle is typically covered with sheepskin which is

basically protection and comfort for the horse.

Added to

the saddle is “hardware” such as the “D” fixtures or “rigging”, to which the

latigo and billet attach to secure the cinch.

The stirrup is attached with the fender, and the leather behind and

below the cantle is referred to as the skirt.

Some

saddles have a second cinch that is positioned below the cantle. The second cinch keeps the back portion of

the saddle from tipping upward when a rider dallys a

rope to the saddle horse to stop a steer, jerk a calf or pull a log.

The

construction of the fork, saddle horn and seat of the saddle will vary

depending upon the type of saddle.

For

riding cutting horses, the fork of the saddle is high

and the horn is more narrow and taller. This allows the rider to hold the horn

and brace himself against the fork when the horse is working a cow. The cutting rider sits closer to the front of

the saddle and the seat usually allows free movement of the rider.

The reining

saddle has a wider lower set horn, the forks are not as tall as that on the

cutter and seat is deeper to allow more stability for the rider. The fenders of the reining saddle swing

forward and back freely, allowing the rider to balance himself during a sliding

stop by moving his feet forward.

The

roping saddle has a wide and slightly taller horn and is very strong. The fenders of the saddle are set slightly forward

and have little forward or backward swing making the stirrups steady when the

roper stands to throw his loop. The seat

is deep, and, of course, the saddle has a second cinch. The stirrups of the roping saddle are wider

and longer than other saddles. This is

helpful to the calf roper when they need to dismount quickly without getting a

foot caught. The roping saddle is the

most sturdy and heaviest western saddle.

There

are two types of western pleasure saddles.

The first is a general, multi-purpose saddle; a saddle a weekend rider

or a trail rider would find most useful.

This type of saddle is built primarily to be cost effective. The seat is usually average in depth and the

fenders are usually set slightly forward.

The quality of leather used on this type of saddle is usually not as

high as that used on a specialty saddle.

The

second type of pleasure saddle is that used in the show pen. These saddles are

often custom built, use the highest quality leather and are most often hand

tooled. They are accented with sterling

silver plates and conchos.

There are

two types of seat for the show saddle; the pleasure

seat, which is not as deep as the roper, and the horsemanship seat, which

pushes the rider’s pelvis forward slightly.

The

fenders of the show saddle are hung almost directly beneath the seat to allow

the rider’s leg to hang directly below the hip.

The

barrel or game saddle is the western saddle’s version of a race saddle. It is built with weight in mind. The skirt is shorter, the seat is very deep and the saddle is very lightweight.

The

fenders of the game saddle are very loose, swinging forward and back very

easily. The horn of this saddle is a

little narrower to allow the rider to hold on easily when making a sharp turn.

The last

type of western saddle you need to be aware of is the training saddle. The training saddle is most like the show

saddle, except it is made in plain leather and has D hardware attached to the

front and behind the cantle. These D fixtures are used for bitting-up

horses. These saddles are generally a

bit lighter; the fenders are very loose and often made with “rough-out”

leather. Rough-out leather is not

smooth; it resembles suede. This rougher

surface will give more “grip” to the rider’s seat and leg, and that can be of

benefit when riding a young or spooky horse.

The training saddle is made to be very durable and comfortable.

Regardless

of the type, there are a few key areas that need to be checked frequently to

help ensure safety.

Both the off side billet or latigo and the cinching latigo should

checked for cracking or excessive wear.

Both areas will become damp with sweat almost every time they are

used. Overtime the leather may become

dry and begin to crack. A well-used

saddle may show worn areas where the latigo leather has become thin; whether

worn or damaged, the latigo should be exchanged.

The cinch

should receive a visual inspection every single time the saddle is used. Check to see the cinch is in good condition; no broken pieces, and no questionable wear

patterns.

PARTS

OF THE WESTERN SADDLE

Proper

care of the saddle is the best way to ensure it will continue to serve safely.

All

saddles to should be conditioned at least a couple of

times a year. This practice will allow

you to thoroughly inspect the saddle for potential problems, not to mention the

fact that clean equipment will portray a positive image for your business.

All

western saddle seats are measured in inches.

To

measure the size of the seat place one end of the tape measure at the end of

the seat by the pommel, measure to the start of the cantle, the total of inches

is the seat size of the saddle. Western

saddles will range from 13 to 18 inches.

To

determine if the saddle properly fits the rider, observe the rider from the

side. If the rider has never ridden

before or not very often, then it may be necessary to adjust the rider’s

position before making a determination. With the rider sitting in the proper

position, she should be able to place her fist between the back of their seat

and the cantle. If she cannot do this, the saddle is too small. If she can fit more than a fist between the

seat and the cantle, the saddle is too big.

If a

saddle is too small several things may occur:

The rider

may not be able to able to maintain a balanced position. The rider’s constant unbalanced movement

often results in the horse having a sore back.

The cantle is not designed for the rider to brace against for balance;

it is designed to close the seat of the saddle.

When a

saddle is too large, there is too much “play” in the rider’s seat. The rider will be unable to stay in the

balanced position, instead sliding forward and back as the motion of the horse

changes.

Generally saddle purchases are made

without much understanding and purpose.

As the riding instructor, it is your responsibility to see to it the

saddle fits both the rider and the horse.

Neglecting this responsibility will prevent you from providing quality

education.

Price is

most often the primary factor in choosing a saddle. This is a very unfortunate

mistake. Cheap saddles lack both

craftsmanship and quality materials.

Do not

let your students or their horses suffer the complex problems caused by poor

saddle quality and fit; in the long run it reflects directly on your reputation

as a riding instructor.

Not

all saddles are created equal; each saddle has definite purpose. Choose a

saddle for your client, or be sure she purchases one, that allows you to give a

great riding lesson. Do not let the

quality of your work be tarnished by poor equipment.

Flat Saddles

As with

the western saddle, there are different types of flat saddles, each with its

own purpose.

As you

can easily see, any flat saddle has less leather and is a lot lighter than the

western saddle; that doesn’t mean the craftsmanship involved in building the

saddle is any less.

PARTS

OF THE FLAT SADDLE

Just like

its counterpart, the flat saddle also has a tree. The flat saddle also has a gullet, bars and a cantle.

The front

portion of the flat saddle is the pommel, the back the cantle. Underneath the seat and cantle are two pad

like structures, one on the right and one on the left of center; these are

designed to sit on either side of the horse’s spine. These “pads” are referred to as the panels.

The area

between the seat and the pommel is known as the twist. Behind the seat area is

the cantle. To the side of the pommel

and the twist is a small flap of leather known as the skirt, underneath the

skirt is the stirrup bar; the larger piece of leather below the skirt is the

known as the saddle flap. The saddle flap’s placement, as well as its length

will be designed to aid the specific riding discipline selected.

The

“leathers” hang from the stirrup bar and the stirrups hang on the

leathers. The leathers come in various

lengths and widths and are easily adjustable to fit the rider’s needs.

It is

important to note the width of the leather determines how easily the iron is

stabilized. The widths vary from ½ inch to 1 inch. The leather of the ½ inch

width requires more skill from the rider to stabilize his or her leg. The ¾ inch leather requires an effort from

the rider in learning how to stabilize the leg, yet

does not give the feeling of being too thick or in the way as often does the 1

inch leather.

On the

end of the leathers are the irons or stirrups.

Most Hunt

Seat riders refer to the stirrup as the iron.

It is simply a tradition, and Hunt Seat riding is definitely

a discipline that has deep roots in tradition. As part of the Hunt Seat tradition it is important to note that the leathers, irons,

and girth are commonly referred to as “fittings”. Fittings are typically sold separately when

purchasing a saddle.

Under the

saddle flap are three pieces of leather, the billets. The girth buckles to these billets. (A girth generally has two buckles and may be

buckled to the two billets of choice—most commonly the first and third…the

second being kept in reserve.)

Threaded

through the billets is a flap of leather called is the “buckle guard.” The buckle guard is designed to do exactly

what its name implies; it lies over the buckles and keeps the buckles from

becoming accidentally opened and interfering with the rider’s leg. To the front of the skirt and to the top

portion of the saddle flap are the D attachments. These Ds are smaller than

those found on the western saddle. Their purpose is to allow the attachment of

accessories such as a breastplate or standing martingale.

The girth

of the flat saddle has elastic on at least one side and attaches to the saddle

with buckles.

The side

of the girth without elastic buckles attaches to the right side of the saddle,

the elastic side to the left. The

elastic provides a means to stretch the girth and allows the girth to be

tightened easily. Some girths have elastic on both sides

and some have three buckles verses the standard two. The girths are typically

made of leather; however it is not uncommon to see

girths with fleece.

The

saddle seat saddle is the most unique type of flat saddle. Click

here for picture. The seat is very flat and its design places

the rider substantially behind the withers. It is not uncommon for the saddle

seat saddle to have a cut out for high withered horses. This type of saddle is

referred to as a cutback.

The

placement of the leathers places the rider’s leg more forward than the other

types of flat saddles. Ultimately the

saddle is designed for flat work use, not for jumping. Saddlebreds, Morgans,

Tennessee Walking Horses, and Arabians are common breeds you will see being

ridden saddle seat.

The

close contact saddle is another common flat saddle. Click

here for picture. This saddle offers the rider just what its

name implies, close contact. This saddle

may be used for riding on the flat or for jumping.

Riders

competing in classes such as hunter under saddle or hunt seat equitation will

choose a close contact saddle with the flaps placed under the seat of the

saddle. This placement enables the rider

to ride with a slightly longer iron and keep her heel underneath her seat.

Jumpers

will choose a close contact saddle with the flap placed farther in front of the

seat. This type of saddle is also

commonly referred to as a jumping saddle. The placement of the saddle flap in

this manner allows the rider to ride with a more flexed knee and a shorter

leather. The shorter leather causes an

increased angle at the knee; the forward flap absorbs this increased angle.

The seat

of the “jumping” saddle will also be deeper than that used for flat work. The deeper seat provides more stability.

The

all-purpose saddle is the one that does it all. Click

here for picture.

It has longer flaps than the close contact, a deep

seat and knee rolls. Riders new to the

sport will often choose this saddle for its versatility.

The

all-purpose saddle can be used for flat work, jumping, pleasure and trail

riding. These saddles are usually very cost efficient.

If you

plan on providing horses and tack, this saddle is an excellent choice for

economy and options.

The

dressage saddle has the longest saddle flaps. Click

here for picture. The dressage rider will use a very long iron,

which allows maximum contact with the horse’s side. The body position of the

dressage rider mimics that of the western rider. The hip angle is very open

and the rider uses a “deep” seat. The

deeper seat and the maximum leg contact allow the rider to communicate the most

intricate cues to the horse.

All flat

saddle seats are measured in inches. Starting at the pommel, run the tape

measure to the cantle to determine seat size. Flat saddle seat sizes range from

14 to 18 inches.

Saddle Fit

To

determine if the flat saddle fits the rider, follow the same guidelines as

discussed for the western saddle. In addition you will have to evaluate the length of the

flap. The flap should extend about mid way between the riders knee

and ankle. If the flap is too long, the rider will be unable to properly use

her leg.

The

safety check for the flat saddle should include a visual inspection of the

girth. Check each end of the girth to insure the

stitching near the buckles looks solid and has not become worn or compromised.

Check the elastic to make sure it has not become worn or started to tear.

The

leathers should also be inspected for cracks and thinning of leather,

especially where the irons rest. As a general rule it is a good idea to clean a flat saddle

more frequently than a western saddle.

Flat saddles accumulate more sweat from the horse and thus require more

attention.

Western Saddle Pads

There are

so many variations of saddle pads, it’s impossible to discuss them all. In choosing a saddle pad you first need to

consider the purpose. Primarily the

saddle pad is to protect the horse’s back, while it absorbs sweat. The saddle

pad also protects the saddle, and in some cases it may

aid in fitting the saddle.

Felt pads

are simply a piece of one inch felt 32 inches wide and 34 inches long. These pads were very popular during the

seventies and the eighties and are still used quite a bit today. The advantage to the felt pad is that it is

very durable and difficult to destroy.

The drawback is it is difficult to clean, and some horses get the hair

rubbed off in the loin area.

Neoprene

pads are among the newer “hot” items.

They are usually one-inch thick rubber type

substance. The pad is very sturdy and

absorbs concussion well. The major

advantage to neoprene is it can be hosed off and kept clean. The disadvantage is no absorption of sweat,

and some horses may experience an increase in heat production.

Wool-back

pads are nice basic saddle pads. They

are made from synthetic wool and look a lot like a fleece pad. These pads absorb sweat readily and do not

irritate the horse’s back in anyway. The

wool-back pad is usually used with a Navajo to add a little more thickness. The wool-back can be washed fairly easily; the draw back is

hair will become embedded in the pad and in time will not be able to be

removed. The build up of hair may rub on the horse’s

back and create bald spots.

Air ride

pads are popular for western saddles.

The air ride pad has a fleece type bottom that is in contact with the

horse’s back, while the center of the pad is made up of air bubbles, much like

bubble wrap used for shipping breakable items.

The top of the pad is a simple woven cloth.

The air

ride is great for absorbing concussion, while the fleece absorbs sweat. To make it more attractive, it is easily

washed and very durable.

Therapeutic

pads are also available for western saddles. There are many different types and each has its own claim to fame. Some therapeutic pads utilize gel, which

absorbs concussion and distributes weight more evenly across the horse’s

back. Some therapeutic pads have extra

padding in specific areas, such as at the withers.

Be very

careful in choosing a therapeutic pad; be sure you understand how it functions

and what will occur when a horse wears it.

Saddle

pads may help saddles achieve a perfect fit by compensating for a horses conformational imperfection. For example, a horse with a very high wither

may benefit from a pad that has a cut out in the wither area. A horse that has a sway back may benefit from

a wedge pad. The wedge pad will level

the saddle and alleviate excess pressure on the loin.

A word of

caution about “padding up”: think about saddle fitting like you would about

fitting a shoe to your foot. You have to have the right kind of socks on or your feet get sore.

If you were to wear to thin a sock, you might get blisters. If you wear socks that are too thick, they

take up too much room and the shoe feels too tight and

uncomfortable. Wear the right socks and everything is great. Your horse feels the same about his saddle

pad. Don’t make an uneducated decision

about what pad to use. Know how it will

affect your saddle fit.

Flat Saddle Pads

The flat

saddle pad is unique in that not one pad fits.

The type

of saddle will determine the type of pad used.

Each type

of flat saddle pad is cut to fit the shape of the saddle.

The close

contact saddle or jumping saddle is the smallest of the flat saddles. A pad made for the close contact saddle will

not properly fit an all-purpose saddle or a dressage saddle. The all-purpose flat saddle pad is also “cut

to fit”. The dressage saddle pad is

usually a square pad and not cut to fit the outline of the saddle.

Fleece or

wool-back pads: same pluses and minuses as with a western pad. These pads are available to fit all saddles.

Currently on some of the open horse show circuits as well as breed circuits

these pads are not cut to fit the shape of the saddle seat. Instead

they are square under the seat to provide room for the attachment of the

exhibitor’s number. The reasoning behind this is to provide the judge with the

opportunity to easily view the number of the exhibitor without having to walk

toward the rail to view the rider’s number her back.

In the

hunter jumper circuit numbers are still worn on the rider’s hunt coat.

Air ride

pads are available for flat saddles.

Felt pads

are available for flat saddles, however they are seldom seen. It has been my experience that a felt pad is

too stiff and rigid for use under a flat saddle, and often inhibits the rider’s

“feel”.

Therapeutic

pads are available for all types of flat saddles. These pads can be useful for

horses that compete in extremely demanding events such as jumping or

cross-country. Therapeutic pads offer

extra absorption of concussive forces and help soften and distribute the weight

of the rider. When selecting a therapeutic

pad read the manufacturer’s claims about what the pad does and what it doesn’t

do, look at the price of the pad and make your own decision as to it value.

Riser

pads or inserts are typically made of rubber or foam. A riser pad does just

what it says: it raises or lifts the back of the saddle. While the riser pad may level the saddle

appearance, additional pressure is put on the front of the saddle and can

quickly cause a sore back. Before using

a riser pad, reevaluate the fit of the saddle being used.

Fitting the Saddle

Doesn’t

one size fit all? What would it matter

if didn’t quite fit perfectly?

One size

does not fit all, and it is a big deal if the saddle doesn’t fit properly.

A poor

fitting saddle can and will cause a horse to not only become sore in his back,

but in is body as well. The horse’s body

wasn’t truly designed to carry us. His

spine is being pulled down by everything underneath it. Then we put weight on top of it.

As

if that isn’t enough of a problem, how do you think he’ll feel if the saddle

doesn’t fit his back?

With the

horse standing on level ground place the saddle pad over the withers and

slightly forward. Next place the saddle

on the pad. Slide the saddle and pad

backward until they seem to settle into a natural position behind the

withers. Ideally

we want the cantle of the saddle to be level with the pommel, it should not

appear as if the saddle is going down hill.

The

gullet of the saddle will still be slightly over the withers. The girth will be

a few inches behind the elbow of the horse. Now lift the pad up into the gullet

of the saddle, I like to refer to this action as making room for the horse’s

neck.

Lift

the saddle pad into the gullet of the saddle.

You

should be able to fit two to three fingers easily between the saddle pad and

the withers. If this is not possible

then the tree is probably too wide for the horse. A tree that is too wide will apply direct

pressure to the horse’s withers, and can create

sores. It will definitely

inhibit the horse’s movement and the horse attitude, making teaching

with that horse very difficult.

If you are able to fit your entire hand between the withers and the

gullet, then the saddle is too narrow.

A tree that is too narrow will have a pinching effect on the horse’s

back; inevitably causing pain and the horse’s willingness to perform.

If

the horse is not comfortable, you’ll have lots of difficult teaching a good

lesson. If the horse isn’t happy, no one

is going to be happy.

Now

cinch the saddle, but not tightly.

Slide

your hand under the pad on the horse’s shoulder just under the pommel. Repeat

this process on the other side. (Hint: make sure the horse is standing somewhat

square.) The pressure you feel should be

the same.

Slide

your hand under the rear portion of the skirt just shy of seat of the

saddle. You should be able to feel the

saddle in contact with the horse’s back.

If the saddle is not in contact with the back, there will be excessive

pressure on the horse’s shoulders and possibly on the loin. The saddle should contact the back all along

the horse’s side.

Now ride

the horse for at least fifteen minutes.

Be very aware of his behavior. If

he is pinning his ears or swishing his tail excessively, the saddle may be

uncomfortable.

When you

remove the saddle note the sweat pattern on the horse’s back. If there are dry spots, there are saddle fit

issues.

As a

horse develops and ages it becomes necessary to re-fit the horse. As the horse’s body changes there will be

changes to the fit of the saddle. Just

because the saddle fit when he was five doesn’t mean it will fit the horse when

he is nine.

The Western Bridle

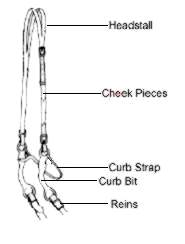

There are

three major pieces that comprise a bridle: the headstall, the bit and the reins.

For bridles that carry a curb bit there is also a chin strap.

It may

seem redundant to discuss the pieces of the bridle; however

I am continually amazed how many people do not know the parts of the

bridle. You should teach it in one of

your very first lessons, then test the student’s knowledge several times.

The

headstall itself has several different pieces and there are many variations of

types of western headstalls. For simplicity sake we will discuss three, the brow band

headstall, the single/double ear headstall and the split ear headstall.

The brow

band headstall is so named because the piece of leather that lies in front of

the ears is termed the brow band. The

piece of leather that lies behind the ears is referred to as the crown piece.

The crown

piece offers attachment and adjustability for the cheek pieces. At the bottom of check pieces, there is an

attachment device for the bit. There are

several ways the bit may be attached.

There may be water ties, or pieces of leather that run thru the double

backed cheek piece. Sometimes there are

buckles used. There may be concho screws

used. (A word of caution about concho

screws: they do become loose in time, and it is necessary to check them

frequently to avoid the bit falling from the headstall.

Brow band

headstalls are commonly used for bridles with snaffle bits or hackamores. We

will discuss different bits later in this lesson.

The

single ear headstall also has a crown piece and cheek pieces. There is not band

across the brow. A single leather piece

attached to the crown piece encircles one ear.

The ear-piece is moveable and can be adjusted

for a comfortable fit. The ear-piece traditionally encircles the right ear.

When

there is an ear-piece around each ear, it is a

double-ear headstall. The ear-pieces do slide on the crown piece and can be adjusted

for a comfortable fit. This design

allows for more detailed placement of silver barrels and braiding.

Single

ear or double ear headstalls are commonly used for bridles that carry a curb

bit.

The split

ear headstall resembles the single ear headstall. The difference is the hole for the ear is not

adjustable, but is instead a sewn piece of leather or

literally a split in the crown piece allowing for insertion of the ear. The

problem that occurs with this headstall arises with the need for adjustment;

there virtually is no adjustment.

SPLIT

The chin

strap or curb strap is a piece of leather or chain which attaches to the bit

and lies underneath the horse’s chin. If

a chin strap is made of leather the intensity or pressure is less than if the

chin strap was made of chain. When we

discuss curb bits we will talk more specifically about the role of the curb

strap.

There are

four basic types of reins used for the western bridle.

1. The romal reins are comprised of one single rein attaching to each side of

the bit. At the center of the reins is a

long single braided leather piece with a “popper” on the end—this is the romal.

Romal reins that are made of leather

and are hand braided. The type of braiding is referenced by the number of

plaits. A basic braid romal rein will be 12 or 14

plait. A 16-plait romal

rein is a little thicker and heavier.

Regardless of the number plaits

involved in the making of the reins, they may be made solely of leather or may

have rawhide woven around them or silver barrels placed around the

leather. The length of the romal rein varies depending upon what event they are used

for. Working cow horse riders use a

54-inch rein. Riders competing in trail classes use a 58 or 60-inch rein.

Another factor that determines

the length of rein is the length of the horse’s neck—long neck, long rein.

The proper way to hold a romal rein is to have one hand closed around the rein

portion with the rider’s thumb on top.

The hand should be held in the same manner as if you were eating an ice

cream cone. The other hand holds the

tail of the rein, and usually rests on the rider’s leg. The hands should be no closer than 16 inches

on the reins. This position allows the

rein hand to move freely with out “hanging up” on

tension created by having a shorter distance between the hands.

Romal reins are

also available in round harness leather, braided rope and regular rope. These reins are substantially lighter than

the braided reins, but are sufficient for the weekend or trail rider.

2.

The single rein is another common

rein used with the western bridle. It is

very similar to that used on standard hunt seat bridles, but is usually shorter

in length. The single rein is just what

it implies, one end of the rein attaches to one side of the bit and the other

end of the rein attaches to the other side of the bit. These reins are available in rope, leather,

braided leather, or nylon.

The events that use the single

rein include roping and “games”. Trail

riders also like to use the single rein since it eliminates the possibility of

accidentally dropping one rein when out on trail.

3. Split reins are the most popular type of rein used with a western

bridle. Two reins make up split

reins. One rein attaches to one side of

the bit and the other rein attaches to the other.

Split reins are used with snaffles

and curb bits. They may be held with two hands or one. If split reins were held with one hand, the

rider’s palm would be facing downward toward the neck of the horse, one rein

would be held between the thumb and the index finger with the other rein being

held between the index finger and the third finger.

In the show ring it is only

permissible to have one finger between the reins, and the reins are carried on

the side of the horse corresponding to the hand being used by the rider……right

hand, right side, left hand, left side.

When the reins are held with two

hands the tail of the reins should cross over the horse’s neck and both reins

are held in each hand.

The highest quality split reins

are made from harness leather. Latigo leather split reins are also available.

The widths available are ½ inch, 5/8 inch and ¾ inch.

The ends of the reins that attach

to the bit may utilize water ties, concho screws or buckles. A word of caution about reins that use

buckles: if you use a running martingale, the buckles may catch on the rings of

the martingale, thus trapping the horse. This will not happen with reins that

use water ties or concho screws. Water

ties are by far the best way to secure reins to the bit.

4. The final type of reins to

consider are draw reins. Draw reins do exactly what they imply, they

draw the horse’s head toward the chest.

The draw rein may be a single

rein or two reins. Attachment is to the

side rings or the cinch or to the Ds at the middle of the cinch under the

horse’s chest. The rein then goes from

attachment through the snaffle bit cheek piece (or the curb rein attachment

point) and back to the rider’s hands.

When the rider sets her hands,

there is no direct contact with the bit…instead the indirect contact of the

rein forces flexion of the horse’s neck and poll.

Only a very experienced rider

should use draw reins. Do not try to

teach a beginning rider while draw reins are in place. Used improperly, the draw rein can cause a

horse to feel trapped and behave in ways that can cause serious injury. When choosing to use draw reins always take

into account the temperament of the horse, experience of the rider and the

choice of the bit. These reins are not

intended for the beginning rider!

The Hunt Seat Bridle

Hunt Seat

riding is deeply rooted in tradition, so it is no surprise that all Hunt Seat

bridles components are essentially the same. The Hunt Seat bridle has a crown

piece, check piece, throatlatch and brow band just as the western counter part. But it

also has a noseband which is attached to the bridle.

The area

where the bit is attached to the bridle is significantly different than that of

the western bridle. It has a small cut

in the leather that fits over a bent piece of metal sewn into the leather. The Hunt Seat bridle has another unique

trait, “keepers.” “Keepers” are loops

of leather designed to hold the “tails” of the bridle. The tails are the pieces that allow bridle

length adjustments.

The reins

of the Hunt Seat bridle may be all leather with a braiding interwoven, or

leather with rubber in the area of the hands.

Hunt Seat reins may have a small buckle where they join at the rider’s

hands. They are available in many

different lengths; the size of the horse and the event determine the choice of

length.

Jumping

horses typically require less rein length than a hunter under saddle

horse. A pony would also need a shorter

rein.

Bits

It seems

from the beginning of time man has been determined to reinvent the wheel so

speak. The variations and promises of

bits are so numerous one would assume horsemanship is not needed.

There are

only two basic types of bits: the snaffle, and the curb. One is not superior to

the other, neither work miracles. Both can be effective in communicating with

the horse with the proper training of the rider.

The

purpose of the bit is simple, it gives added control to the rider, and it also

gives an opportunity to create a refined line of communication.

Snaffle

bits are those bits that have a direct action on the horse’s mouth. The reins

attach opposite the mouthpiece, there is no poll action and no curb

action. The bit pressure is applied to

the corners and bars of the mouth.

Whatever pressure is applied to the rein is applied equally through the

snaffle to the horse’s mouth.

There are

several different styles of snaffles available, all determined by the discipline

of riding, education level of the horse and education level of the rider.

The cheek

pieces of the snaffle are available with four different types. The reins attach to the cheek piece that can

be “O”, “D”, eggbutt or full check.

The “O”

slides through the mouthpiece. All the

others are fixed cheek pieces and will not rotate. The “O” may pinch the corner of the horse’s

mouth as it slides through the mouthpiece.

If this occurs the use of bit guards may be of benefit. Bit guards are

round pieces of rubber that lay between the side of the horse’s mouth and the

“O”.

It is

important to note that horses of any discipline may use any of the snaffles

listed.

Mouthpieces

of the snaffle may be one, two or three pieces. Some of the types of mouthpieces

available are: smooth--the bar stock, which is the actual piece in the horse’s

mouth, is smooth, it is slightly wider toward the corners. Smooth snaffles are used for breaking colts,

for horses with very sensitive mouths or for hunter and jumper horses.

Twisted

snaffle: the bar stock of the twisted snaffle is comprised of one large piece

twisted to two smaller pieces of bar stock. The degree of severity of the

twisted wire depends upon the size of the bar stock used and the shape of it. Round bar stock is less severe than square

bar stock.

Covered

or wrapped snaffles: these are smooth mouthpieces that are wrapped in plastic

or leather, increasing the diameter of the bit. Usually, the larger the

diameter of the mouthpiece, the less severe the bit; the smaller the diameter

the more severe the bit. This is true,

only if the bit fits the horse’s mouth.

Before

selecting any bit, you should measure the width of the horse’s mouth, determine

the amount of tongue the horse has and determine the depth of palate for each

horse.

Kimberwick bits: Kimberwicks

are used in flat saddle riding.

The Kimberwick mouthpieces include smooth as well as ones with

a port. A port is an elevated “U” shaped

piece of bar stock in the center of the bit.

The Kimberwick has two rein attachment

points…one opposite the mouthpiece and one below, allowing the bit to be used

as a snaffle, or a curb. If it is used

as curb, it then needs a curb strap.

Because

the Kimberwick can be used as a snaffle or a curb, it

is a nice choice for riders who are just learning to ride.

A curb

bit has the reins attach below the mouthpiece.

It is a lever action bit. When

the rein is moved backward, the shank of the bit moves backward, rotating

around the mouthpiece, which is the fulcrum of the lever. In doing this there is pressure applied to

the horse’s mouth by the mouthpiece of the bit, pressure to the chin groove by

the chin strap and pressure to the poll by the crown piece of the bridle.

The

amount of pressure applied by the mouthpiece is a ratio…the length of the shank

to the length of the cheek piece of the bit.

If the shank is 3 inches, for example, and the cheek piece is 1 inch,

then the applied pressure is 3 to one.

One ounce of pressure on the reins and 3 ounces of pressure is applied

to the mouth.

Shank

lengths of curb bits are typically 6” or 8”.

There are several junk bits that have shorter shanks, these bits in my

opinion are the most ineffective and offensive to the art of horsemanship.

There are

two common shapes of shanks, the curved shank, such as that found on a grazer

bit, and the straight shank. The straight shank bit will ask for more flexion

at the horse’s poll in comparison to the curved shank.

The

second piece of the curb bit is the mouthpiece.

Mouthpieces of the curb bit are numerous, but they all have only one

purpose---to be uncomfortable. The

mouthpieces may be of straight bar stock, and may or may not be broken or

jointed. They may include a port; ports

are available in many different heights, and widths. The higher the port the more pressure applied

to the roof of the horse’s mouth. The

wider the port, the less the tongue carries the bit, making the bars carry more

of the weight.

Quality

curb bits are generally inlaid with copper.

Very seldom will you find a curb bit with a solid copper mouthpiece;

cooper is very soft and easily chewed.

Curb bits

offer a beginner rider more stop than a snaffle. Knowing you can stop will

prove to be a mental asset to these riders.

A word of

advice on curb bits; choose a bit that suits the job. Do not select a high port bit for a rider’s

first lesson. Choose one that will not

punish the horse when the rider makes the inevitable mistake of pulling or

hanging on the reins.

A good

quality curb bit will cost $125 and up, but will last a life time. Bits are an investment every riding

instructor needs to make. Having the

right bit for the right horse to match the rider’s skills is extremely

important and brands you as professional or unprofessional.

To learn

more about bits take the online course Bits, Saddle Fitting and Hoof Balance at

HorseCoursesOnline.com Click

here to see a course description and outline.

Curb

straps may be leather or chain. Leather

is, of course, softer than chain.

Western bridles use curb chains with a leather attachment while riding

bridles use “J” hooks to attach the curb chain.

When a curb strap is properly adjusted, two fingers will easily fit

between the curb chain and the horse’s jaw.

You change the length of the curb strap to meet the need…how quickly do

you want curb strap pressure?

Accessory equipment

Martingales: for western horses there is one type of

martingale, commonly referred to as a running martingale, or a training

fork. It is comprised of a piece of

leather connected to the center ring of the cinch, running between the horse’s

front legs and toward his head. The leather piece is split and it has two rings

attached. The reins are run through the rings of the martingale and then to the

rider’s hands.

Although

it is not uncommon to use a martingale with either a snaffle or a bit, I recommended

that martingales be used only with a snaffle.

Split reins with water ties are the best reins to use with a martingale.

Reins with snaps may become entangled in the rings of the martingale and cause

a horse to panic.

Flat

saddle horses may use two different types of martingales. The running

martingale is similar to that of the western horse, except it has a neck piece,

this piece of leather which lies around the horse’s neck simply holds the

martingale on the horse. When flat saddle

horses use a running martingale they also use rein stops. Rein stops lie between the martingale and the

bit, they stop the martingale rings before they reach the bit, reducing the

potential for the rings becoming hooked on the buckle attachment of the rein.

The

standing martingale has one piece of leather extending toward the horse’s head

with a loop at the end. The noseband of

the bridle runs thru this loop. It is similar to a western tie-down. Standing

martingales are most often seen on Hunter and Jumper horses. The standing

martingale allows the horse to lean against the noseband for balance.

It is

essential you know if the horse accepts the use of any type of martingale.

Never add

a martingale to a horse’s routine for the first time with an inexperienced

rider. Horses can be very unpredictable;

do not assume a horse with a quite disposition will accept any

thing.

Always

use an educated judgment based upon knowledge of the horse, equipment and past

experience. Safety first is the

responsibility of the riding instructor.

No matter

the discipline you teach, it is your responsible to teach the proper rider

attire.

Tennis

shoes, hiking boots and any other type of foot wear other than a traditional

riding boot is not acceptable.

These

days people seem to be in to convenience; they like boots with rubber soles

that have grips on the bottom, they like the shoe that has a heel like a boot,

and they like open toe shoes. when stopping by the barn. You have the responsibility to set the rules

and to maintain safety. Only riding and

work boots are acceptable in the barn area.

Rubber

grips within the stirrup are also not acceptable. The keep the rider from making a subtle

adjustment as the sole of the boot will not slide. If a rider gets into trouble, rubber does not

allow them to slip their foot out of the stirrup; it may actually cause further

injury to rider.

The

riding shoe is simply an embarrassment to the tradition of riding. As instructors we are responsible for

preserving the tradition of riding.

Riding

boots are designed to protect the rider’s foot and leg. Riding boots are designed to interact with

the art of riding, allowing the rider to be able to make subtle

adjustments. Riding boots allow for an

easy dismount in an emergency.

Riding is

not a sport of convenience; it is a sport of tradition and dedication.

Always

honor, preserve and teach the tradition of riding.

Chaps can

be a very useful addition to a student’s riding gear. Many flat saddle students

utilize what are known as schooling chaps. Theses chaps are simple, usually

smooth leather, keeping the rider’s leg from being pinched by the stirrup

leathers. Chaps also save wear and tear

on the rider’s expensive show boots.

Half

chaps are small chaps that only cover the rider’s lower leg. They either zip on

or Velcro on. These are less expensive than a pair of full chaps and serve the

same purpose.

Western

show horse riders typically only wear chaps in the show ring. These chaps are custom made to fit the rider,

come in an array of colors and may be either rough-out or smooth leather. Show chaps are often accented with a silver

concho in back and a three-piece silver buckle.

I

strongly recommend all riders under the age of 12 be required to wear a

helmet; as should a beginner rider of any age.

When

children and beginning adults are riding for the first time they are not only

going to make mistakes, they are going to be searching for their center of

balance while on a moving animal.

Anything could happen. As

instructors we want to put safety first.

Requiring

the use of a helmet is simple.

The

selection of a helmet is simple. The

equine industry has spent a lot of time and money developing a helmet that

offers outstanding protection. When

purchasing a helmet for your business or advising a client on the type of

helmet to purchase always stress it must be a safety-approved helmet.

Most

helmets are approved, tested helmets; but untested and poor quality helmets are

still being offered.

Spurs are

with out a doubt the most misunderstood riding aid in

the horse world. There is a great misinterpretation that spurs are mean or

spurs are cruel. Spurs can be mean and cruel, but only if the rider chooses to

use them that way.

The

purpose of spurs is to offer an extreme subtle communication opportunity from

the rider. It allows the rider to subtly

communicate almost unseen adjustments in the horse’s body. Used properly, spurs will aid the rider’s

performance.

Flat

saddle riders use a stainless steel spur with a blunt point at the end. The spur shank length varies from ¼ of an

inch to 1 inch. The spur is worn high on the heel of the boot.

Western

riders have about 200 choices when it comes to spurs and spur design. There are approximately 20 different types of

rowels and 20 different lengths of spur shanks and angles.

Teach

your students that the key to spur use is in the understanding the spur is an

aid, not a punishment. Use caution and

good judgment when adding the use of spurs to a learning rider’s lesson. They

can improve communication, but they can also cause disaster.

Whips,

crops or bats are designed to be used aids.

Their purpose is to reinforce the leg and help send the horse forward.

Most

commonly used with hunter horses and dressage horses, the use of this aid can

improve the level of a horse’s performance.

I do not

recommend the use of whips, crops or bats for beginning riders.

As with

the selection of any aid, err to the cautious side.

Who Provides Equipment?

Should

your riders provide their equipment, or should you?

The

answer, of course depends on how you run your business and/or the desire of the

facility out of which you teach.

If the

rider is using a horse that you provide, I recommend you provide the

equipment. We discussed the importance

of saddle fit and care of the horse. The

lesson horse plays a major role in how profitable you

business is. You do not want to risk

this valuable asset.

The horse

should be ridden in a bridle that you know he is comfortable wearing and is

suitable for the level of performance he’ll be asked to provide. A horse will not go in just any bit because

we choose to use it.

We make

our bit selection after considering the configuration of the horse’s mouth (See

the online course, Bits, Saddle Fitting and Hoof Balance) and his level of

training.

If the

rider owns the horse, then the rider should supply the equipment use with your

approval. Checking and deciding on the

correctness of the equipment is part of your responsibility as the

instructor. Often those just embarking

on the journey of riding horses base their purchases on how much something

costs. They are just learning, so they do not know how to evaluate quality much

less function.

If a

rider has a saddle that does not fit the horse, immediately explain why, and

show them the problems.

If the

bit is not a quality bit and is not working well with the horse, discuss it with

the rider. Select another bit you feel

will work better. Have the rider try it.

Direct

the rider in the purchase of more productive equipment.

Your job

as a riding instructor is to educate, not judge.

Always be

productive when teaching…. explain why, and then explain and show an example of

a higher quality piece of tack. The tack

chosen will determine how well the rider can communicate with the horse. It will be a determinate to the level of

riding achieved.

ASSIGNMENT:

1. Describe in detail how to

determine saddle fit. Take a picture of

a saddled horse, and discuss whether or not the saddle fits properly and why.

2. Explain the difference between

a snaffle and a curb bit. In your opinion describe which type of bit you would

choose for your students and why.

3. List and briefly describe the

different flat and western saddles.

4. Who is ultimately responsible

for the achievements of the student, the comfort and care of the horse, and the

overall safety of the instruction program?

Please send your report to cathyhansonqh@gmail.com